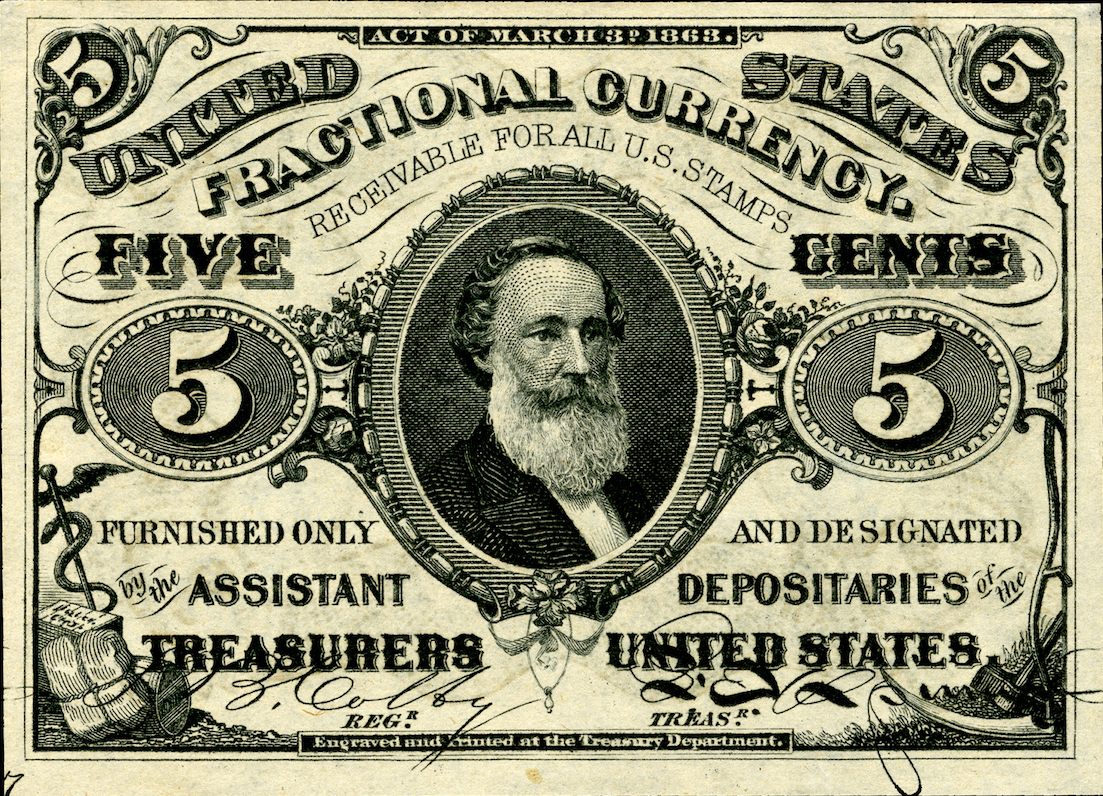

A Treasury Official in 1866 Put His Own Face on U.S. Currency

The bill was supposed to feature explorer William Clark instead.

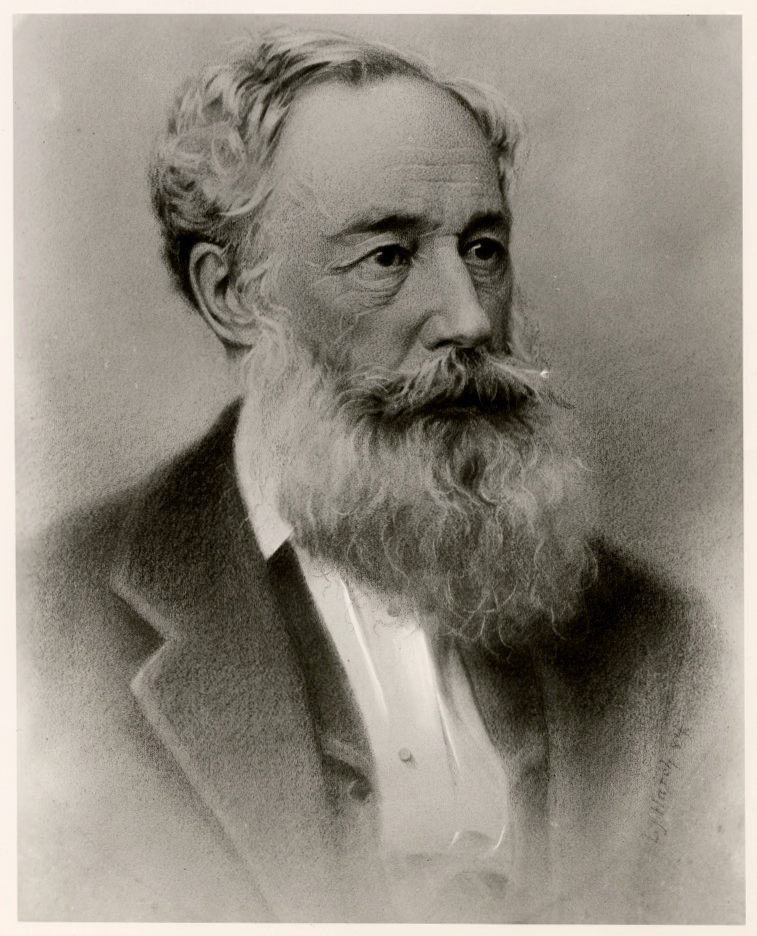

In 1866, Spencer M. Clark, then Superintendent of the National Currency Bureau, made a daring decision: to print his own face on U.S. currency.

Clark, who served as Superintendent from 1862 to 1868, had no authorization from his superiors to do this. But U.S. paper bills were in flux because of the recent introduction of fractional money, and as the supervisor of the new bills, he was in a unique position to influence the design.

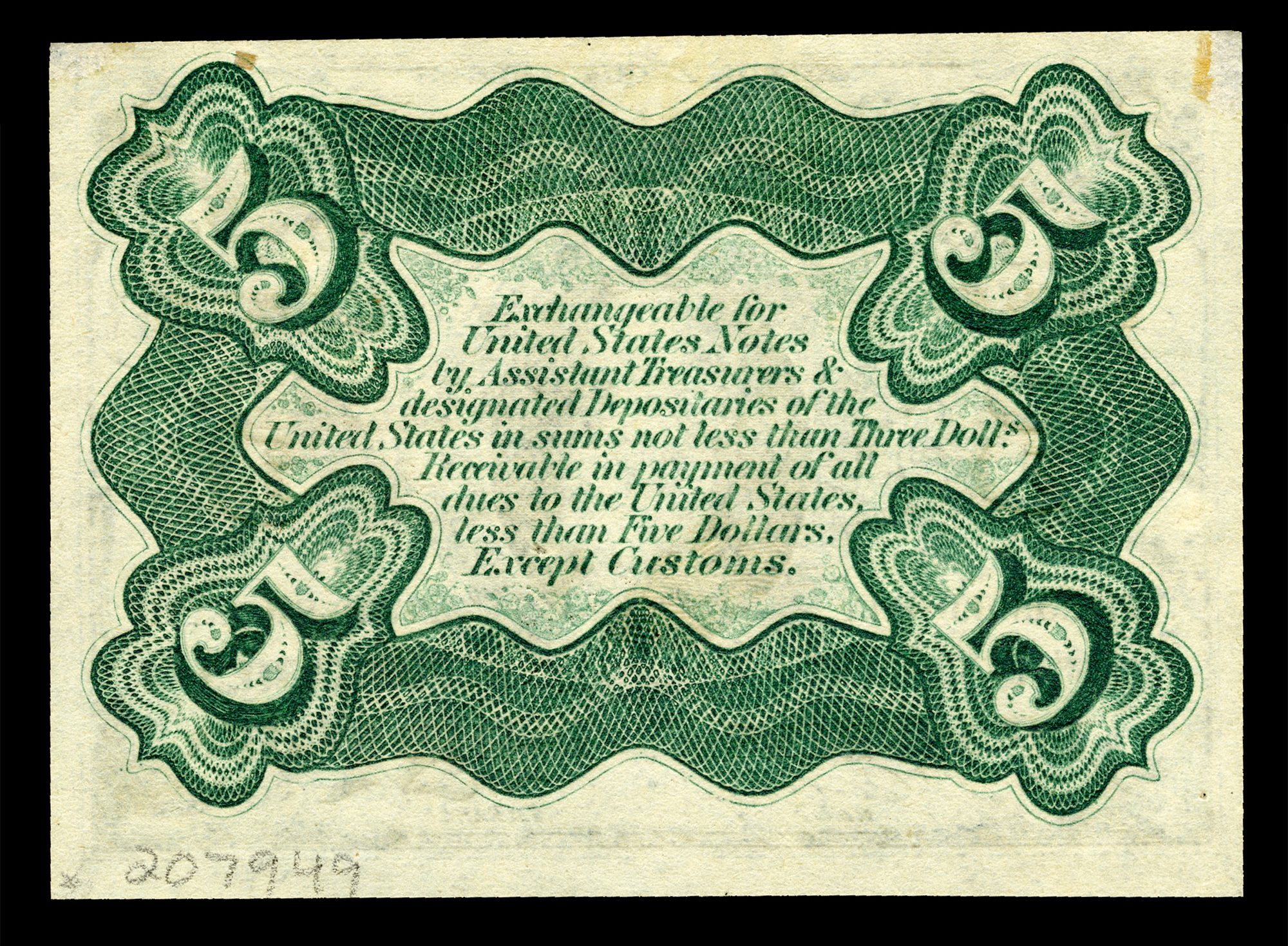

From 1862 to 1876, the U.S. Treasury issued fractional money to combat a growing coin shortage. “At the beginning of the Civil War,” according to the website Antique Money, “people started hoarding coins for their precious metal content.” To avoid a crisis, the Treasury introduced paper money to represent a cent amount rather than a dollar amount. These fractional bills were physically smaller than dollars and consisted of three-cent, five-cent, 10-cent, 25-cent, and 50-cent notes.

It was the third issue of that five-cent note that caught Clark’s attention. Congress had asked for the note to honor William Clark of the Lewis and Clark explorations. But allegedly, the document that reached the Treasury specified only that the new bill should honor “Clark,” without clarifying which one—and Spencer M. Clark, despite surely knowing Congress’s true intention, seized the opportunity to print his own face on the bill.

The move infuriated Congress. Clark was already roundly disliked because of the scandals he had brought the federal government. Two years earlier, in 1864, the House of Representatives investigated his department after Representative James H. Brooks claimed the Treasury had become a “house for orgies and bacchanals.” Clark was accused of “hiring women based on their looks rather than their ability”; female employees described how he “plied [them] with oysters and ale and made ‘improper’ overtures to them.” In fact, one woman told Congress that he had “offered her first $100, then 10 times that amount, for a tryst with her.” (An investigating body, however, concluded that these claims had no basis and that Clark was the victim of a “conspiracy.”) By the time he printed his own face on U.S. money, Congress had little patience remaining.

One Congressman in particular—Pennsylvania Congressman Russell Thayer—”took immediate exception” to Clark’s five-cent note when he learned of it in February 1866. That March, he amended an appropriations bill to say “hereafter no portrait or likeness of any living person shall be engraved or placed upon any of the bonds, securities, notes, or postal currency of the United States.”

In advocating for his amendment in Congress, Thayer said:

I hold in my hand a five-cent note of this fractional currency of the United States. If you ask me, whose image and superscription is this? I am obliged to answer, not that of George Washington, which used to adorn it, but the likeness of the person who superintends the printing of these notes … I would like any man to tell me why his face should be on the money of the United States.

Thayer’s feelings on the subject of living people adorning bank notes were hardly ambiguous. “It is derogatory to the dignity and the self-respect of the nation,” he said in Congress. “I trust the House will support me in the cry which I raise of Off With Their Heads!”

After some debate, on April 7, 1866, Congress passed the Thayer amendment—enshrining into law for the first time the rule that U.S. money can only feature deceased individuals.

But, to the legislature’s chagrin, the act did not apply to currency already in existence. It took a second proposal—a May 1866 law that “prohibited the issue of any note with a denomination of less than 10 cents”—for the Treasury to stop printing money in Clark’s image.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook