Secret Underground Water Stores May Help Trees Survive Droughts

According to a new study of “rock moisture,” bedrock is a lot wetter than expected.

When drought ravaged California in the first half of the 2010s, it caused a treepocalypse. Weakened by lack of water, parched oaks, firs, and pines succumbed by the hundreds of millions to pests, fungi, and disease. The state government’s Tree Mortality Viewer still shows the carnage, with red dead zones stretching across the state like a trail of blood.

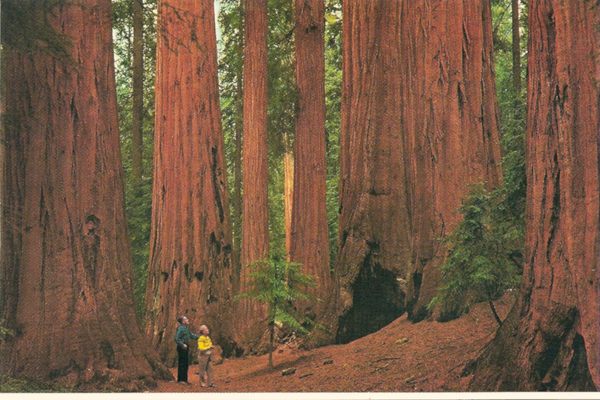

As their brethren shriveled up around them, though, a stand of trees in northern Mendocino County stayed lush and green. How did they do it? Just the way the survival handbooks tell you to: via a secret store of water, deep underground.

In a new paper in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), researchers detail the results of a four-year study during which they measured the water stored in the bedrock at the Eel River Critical Zone Observatory. The observatory is part of a worldwide network established to learn more about Earth’s “critical zone”—the thin layer of the Earth’s surface, from the bedrock on up, that influences and is influenced by human life.

The amount of water they found was “beyond our wildest imagination,” says the study’s lead author, Daniella Rempe. The rocks at the site were able to hold onto nearly 30 percent of the year’s accumulated rainfall, more than the soil itself. They also may contribute to a kind of rationing system, parceling water out to the trees above them all year long.

As Rempe explains, hydrologists have long known how to measure surface water, which stays near the top of the soil, and groundwater, which sinks beneath the bedrock layer and feeds into streams. But water also stays in the bedrock, in the form of droplets that hang from crevices, or thin films that layer on the rock’s surface. Quantifying these drips and drabs is more complicated. “With soil, you can look at individual particles, or poke instruments in directly,” Rempe says. “In rocks, you can’t really do that.”

For this study, the scientists drilled nine wells in the forest’s bedrock, and used neutron probes to measure the hydrogen present in the wells. They then deduced how much water gathered each year, and how long it stuck around.

The results, Rempe says, were “pretty tremendous:” each well ended up receiving between 4 to 21 inches of water per year, meaning the rock stores up to 27 percent of the annual rainfall. The bedrock appears to have a maximum capacity, sloshing anything extra into the groundwater store instead. As Rempe puts it, “The cup gets full, and then the size of the cup dictates how much water is available over the summer,” ensuring a steady, rationed supply.

And while the soil dried out relatively quickly after rain stopped falling, the rock was able to hold onto the water for much longer. This may explain why the trees were able to survive the drought: “Because the cup gets full even in a drought year, that place might be particularly resilient to mortality that relates to water stress,” says Rempe.

Many mysteries remain. For one thing, it’s unclear exactly how the trees pull the water out of the rock’s tiny openings. (Like most trees, they likely get some help from symbiotic fungi, whose thinner hyphae, or branching filaments, can wind their way in there.) Researchers also aren’t sure why trees in other places—the Sierra Nevada, for example—succumbed to the drought in such large numbers, even though they also sit on water-storing bedrock. Scientists are looking into this, as well as some basic questions about the storage system itself, Rempe says: “Where exactly is the water, and why is it stored where it is?”

Some lessons we can take away immediately, though: Be prepared. Don’t guzzle all your water at once. And, of course, it never hurts to hide your supplies deep underground.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook