When Life Gave Pennsylvania Spotted Lanternflies, Its Bees Made Spotted Lanternfly Honey

A smoky-sweet flavor, courtesy of an invasive species.

For seven years, Pennsylvanians have been on high alert for an invasive species: the spotted lanternfly, which hitched a ride on a shipment of stone from its native China before landing in agrarian Berks County, an hour outside Philadelphia. Since then, the leafhopper, which has no natural predators in the region, has spread throughout the southeast corner of the state.

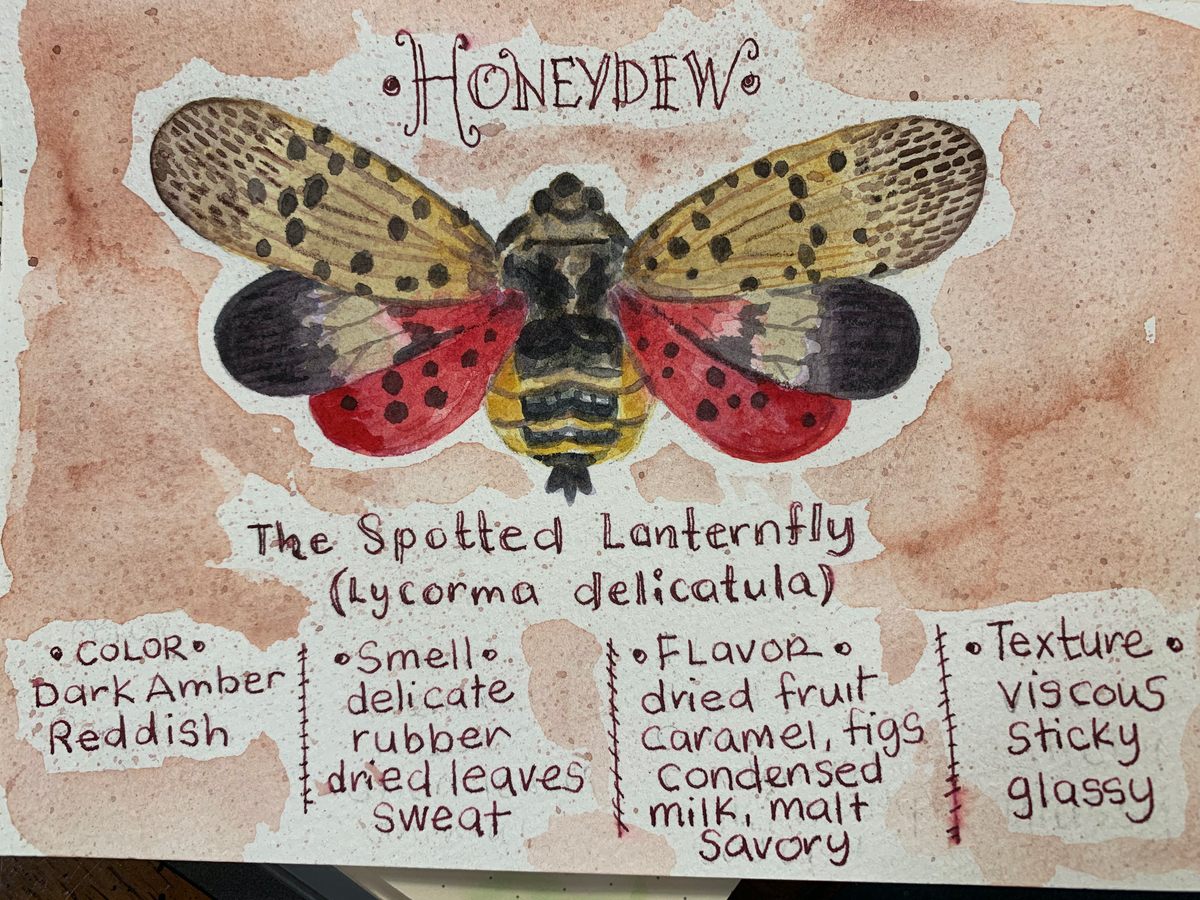

With gray and scarlet wings adorned with black polka dots, the spotted lanternfly would be pretty if it weren’t so destructive. It flutters from plant to plant, feasting on the sap from more than 70 different species. Unchecked, crops such as grapevines, hops, and trees including apple, maple, cherry, and pear wither and develop black sooty mold: So far, the pest has done an estimated $43 million in damage.

By 2019, the insect had spread to Philadelphia, breeding on street trees and green spaces and littering sidewalks in the city’s concrete center. The state’s Department of Agriculture encouraged residents to scrape egg cases from trees and squash adult specimens on sight, but that hasn’t been enough to defeat this pervasive pest. Now, beekeepers have discovered that spotted lanternflies are affecting the region’s food supply in another way: They’re messing with its honey.

Don Shump, owner of Philadelphia Bee Co., has tended hives around the city for more than a decade, harvesting and selling neighborhood-specific varieties, donning bee beards at educational workshops, and extracting colonies of honeybees, wasps, and hornets from places they don’t belong. One day in fall 2019—right around the time the first adult spotted lanternfly populations exploded in Philadelphia—he entered the honey house, where a coworker was processing the harvest, and was hit with an unfamiliar aroma.

“It smelled like maple bacon,” Shump says. “I didn’t know what these girls had gotten into, but it was something different.”

The harvest looked different, too: thick in texture with a deep reddish-brown color. Late summer and fall, when asters, goldenrod, and Japanese knotweed are in bloom, is the season for dark honey. But Shump had never seen anything like this, and beekeepers around Southeast Pennsylvania were seeing the same thing—an unusually dark harvest with a surprisingly smoky, robust flavor.

Variations from season to season and year to year aren’t uncommon. Honey will naturally shift in character as temperature and weather influence which plants contribute to spring and fall nectar flows. Humans can affect it, too: A Brooklyn beekeeper’s honey was tainted with Red 40 food dye when her bees got into the syrup at a nearby Maraschino cherry factory in 2010, and in 2012, bees feeding on discarded M&M candy shells in France produced blue and green honey.

But determining the sources—plant nectar or otherwise—of a honey isn’t always such a straightforward process. Shump had recently worked with academics to research the flora available to honeybees in urban landscapes like Philadelphia by analyzing pollen samples, but that data only indicated which flowers the bees visited, not necessarily the ones from which they collected nectar. He tasted the honey to compare it with familiar profiles, but this new flavor didn’t match any species in bloom at the time.

With no new plant sources in the environment, beekeepers wondered if spotted lanternflies were responsible. To find out—and determine whether the honey was safe to eat—they sent samples to Penn State University assistant research professor Robyn Underwood. A specialist in apiculture who lives in Berks County, she’d studied the relationship between honeybees and the spotted lanternfly, specifically whether pesticides meant to target spotted lanternflies could affect bees and their honey.

One of the spotted lanternfly’s most common food sources is actually another invasive species. Ailanthus altissima, commonly called tree of heaven, is known for its frond-like leaves and propeller-shaped seed pods. So the Department of Agriculture injected some trees of heaven with a pesticide meant to target spotted lanternflies, which would ingest the poison as they fed on tree sap.

In a 2017 research project at Kutztown University, Underwood had found that a small amount of pesticide was detected in spotted lanternfly honeydew, the sugary excrement left behind on trees, leaves, and other surfaces by insects like aphids and scale. (If honey is essentially bee vomit—nectar consumed and regurgitated by honeybees—honeydew is basically bug pee.) Honeybees, which are attracted to this sweet residue, had been observed on honeydew-coated test trees, but none of the toxin was found in honey, wax, or worker bees in hives stationed nearby.

Underwood detected no pesticides in the 2019 honey samples, but she found something else: ailanthone, a bitter chemical produced by trees of heaven to inhibit the growth of surrounding flora and make the plant taste bad to predators.

“Clearly, lanternflies don’t care,” Underwood says. “We think that may have something to do with the flavor of the honey being different.” Additional testing confirmed the presence of spotted lanternfly DNA in the honey. She’s not completely certain that bees are feeding on lanternfly honeydew and bringing it back to the hive, but, she says, “We have bits of data that point to that. Everything is triangulating.”

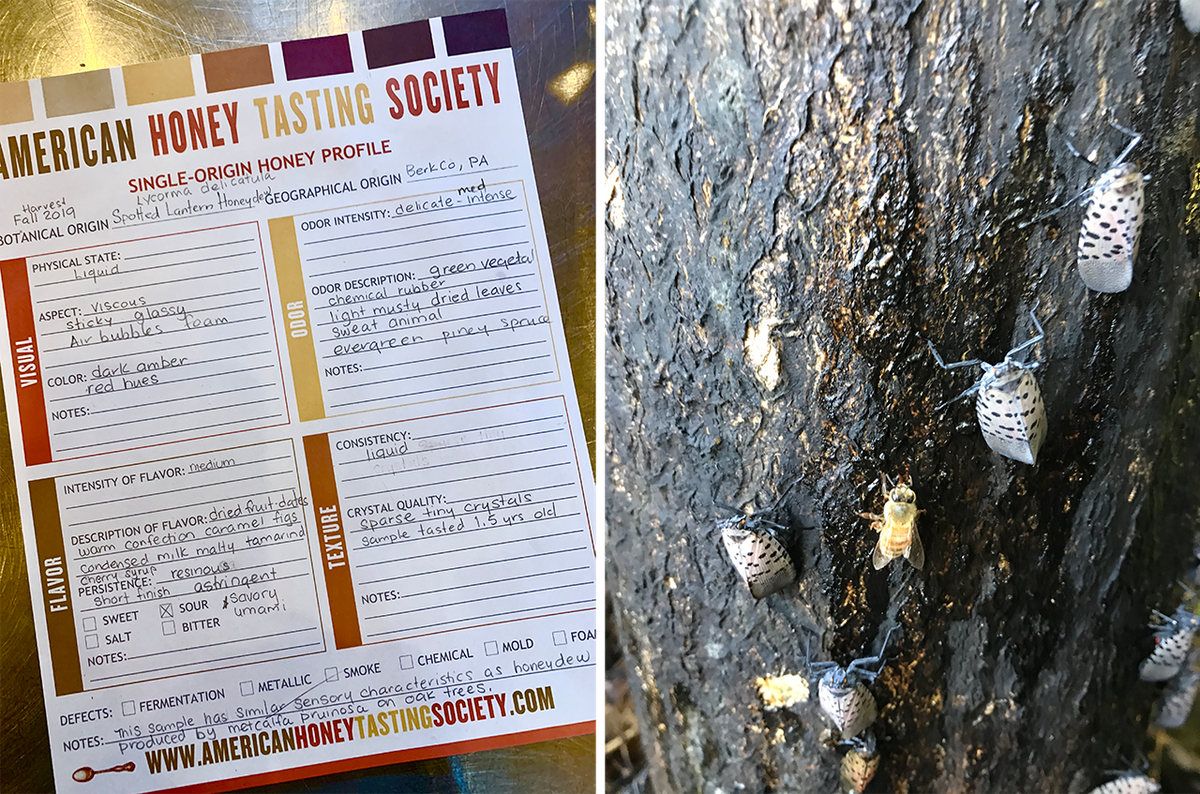

If Shump’s unusually smoky honey is derived mostly from insect honeydew rather than flower nectar, it’s technically a honeydew rather than a honey, says Carla Marina Marchese, a honey sensory expert and founder of the American Honey Tasting Society. Underwood sent Marchese a sample for sensory evaluation, and before the honey sommelier had even tasted it, she knew the product was different.

An experienced taster can compare characteristics such as flavor, aroma, color, and texture to established sensory profiles of different single-origin honeys to narrow down nectar sources. This sample was thick and viscous, like molten glass—a characteristic of honeydew. The flavor didn’t match honey made from the nectar of tree of heaven flowers, which is lighter, with notes of grape, lychee, and passionfruit. The Pennsylvania product tastes fruity, but “more like a dried fruit, a fig, maybe a date,” Marchese says. “It has a really warm note of confection or caramel.”

Here’s what the experts think happened in 2019 and 2020: As spotted lanternflies feed on trees of heaven, they consume ailanthone, excreting it in their sugary honeydew, which collects on the bark of trees. Honeybees tend to go for the most readily accessible food source, so when there’s not much blooming in late summer—the same time of year adult spotted lanternflies run amok—bees collect their sweet, sugary honeydew as if it were nectar. That uncommonly bold flavor? It’s likely the expression of ailanthone, passed from tree to spotted lanternfly to honeybee.

This shift in terroir hasn’t deterred Shump from selling his fall harvest. He’s collected the spotted lanternfly-influenced honeydew from beekeepers to market under the name Doom Bloom, and reception from consumers and chefs has been positive.

“It was really earthy and intense,” says Philadelphia baker and butcher Sarah Thompson, who blends it into butter and drizzles it over the moist yet crisp-crusted biscuits she sells under the name Tall Poppy. “I thought it tasted like wet leaves, like when you walk through the woods in fall.” Her coworkers—seasoned cooks and sommeliers—picked up bourbon-y, barrel-aged notes, and customers commented on how well the honeydew’s flavor stood up to the richness of the biscuits.

Though the spotted lanternfly has spread as far as Ohio, Virginia, New York, and Connecticut, Doom Bloom remains a regional phenomenon. Beekeepers are only seeing this surprising interaction in Southeast Pennsylvania, where populations of the pest are concentrated.

This gives the product an ephemeral quality: In future falls, spotted-lanternfly honeydew might not be the dominant food source. If the state’s efforts to control and eliminate the pest are successful, this singular sweetener might disappear.

As unsettling as it may be to see not one but two invasive species affecting the region’s honey, Shump sees spotted lanternflies as unharmful to honeybees. In fact, their influence on apiculture could be a net positive: Unlike honeydew produced by aphids, the spotted-lanternfly honeydew gathered and stored by bees is low enough in ash content to serve as an excellent cold-weather food source. This supports healthier, stronger hives, which can better withstand parasitic mites, a much more dire threat.

As long as his girls are thriving, Shump is philosophical about the spotted lanternfly’s impact. “I’m far more worried about our hops and vineyards than I am about my bees,” he says. He compares the situation to Japanese knotweed, an invasive plant whose nectar makes delicious honey. “We’re taking advantage of a bad situation.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook