Creating Disneyland Was Like Building a Brand New City

Even Magic Kingdoms need urban planners.

The Disney theme parks are chock full of amusements, rides, and restaurants, but they’re also small cities that must contend with deliveries, trash, and a steady stream of both employees and visitors. No kingdom, however magic, is exempt from all sorts of pesky needs and demands. People need to be able to move from one place to another, they have to refuel, and, every so often, they’ll need to relieve themselves. Ideally, they’ll accomplish all of this efficiently, and without getting frustrated or dizzyingly lost.

To cater to these less-than-wondrous requirements, the parks are, in reality, self-contained marvels of metropolis-building. Disneyland Park in California has a reliable transit system—the first monorail in the Western Hemisphere, which debuted just as many cities were expressing their love of cars and traffic by laying down ribbons of highway. Walt Disney World Resort, in Florida, innovated with trash: Cans are spaced precisely 30 feet apart, and all of them empty via underground tubes so that family vacations aren’t interrupted by vehicles hauling sun-baked garbage juice.

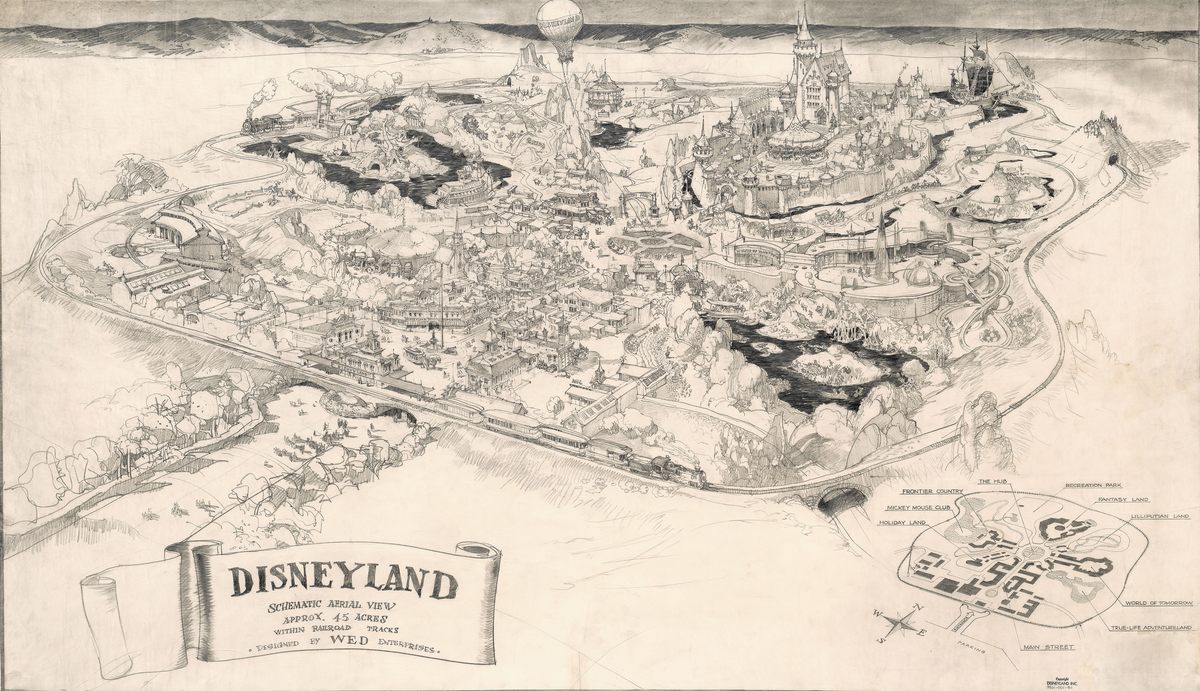

None of this happened by accident. Long before the parks were magic, they were conceived as two-dimensional representations, or as miniatures. Like many city planners, Disney’s chief urban brainstormers and engineers first imagined the parks’ shapes, structures, and logistics, on a small scale.

In the new book Walt Disney’s Disneyland, architecture historian Chris Nichols retraces the long road from idea to the media empire’s first park. To hear one animator tell it, Disney first hatched his idea for a play land while plugging away on Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs in 1937. At the film’s premiere, Disney himself made it a kind of reality superimposed atop Los Angeles. Guests strolled along the median of Crescent Heights Boulevard, which had been reimagined as “Dwarfland” and crowned with a charmingly ramshackle cottage and a cast of costumed characters.

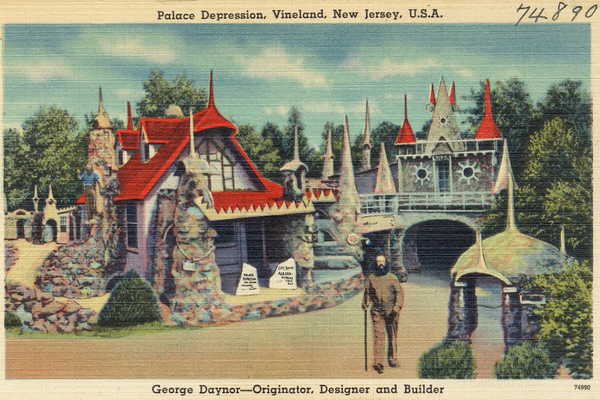

Disney spent years collecting ideas and measuring other places against the one he was building in his mind. He scrutinized Beverly Park in Los Angeles, as well as lavishly ornate miniature rooms and reconstituted historic villages. He combed Henry Ford’s Greenfield Village, near Detroit, and Madurodam, a tourist attraction of miniatures in the Netherlands. He visited Colonial Williamsburg, where costumed reenactors roamed. Then he dabbled. Disney assembled a team of engineers and designers to plan and build a miniature world he dubbed Disneylandia. He imagined diorama scenes built inside train cars, chugging along and showcasing slices of Americana. He brought a prototype—an eight-foot-long hearth scene he called “Granny Kincaid’s Cabin”—to the Festival of California Living in 1952. Visitors crowded around to peek inside, but Disney’s enthusiasm for a full 21-car caravan ultimately evaporated. He thought the project lacked pizazz, so he cast it aside.

Still, Nichols writes, Disney was consumed by the prospect of his own park. Radio and television host Art Linkletter, who traveled with Disney to Copenhagen’s Tivoli Gardens amusement park in 1951, recalled that Disney viewed the trip as reconnaissance. “He was making notes all the time about the lights, the chairs, the seats, and the food. I asked him what he was doing, and he replied, ‘I’m just making notes about something that I’ve always dreamed of, a great, great playground,’” Linkletter remembered. Nichols reports that Disney had blueprints drawn up, and began appealing to local officials for the green light to break ground in California.

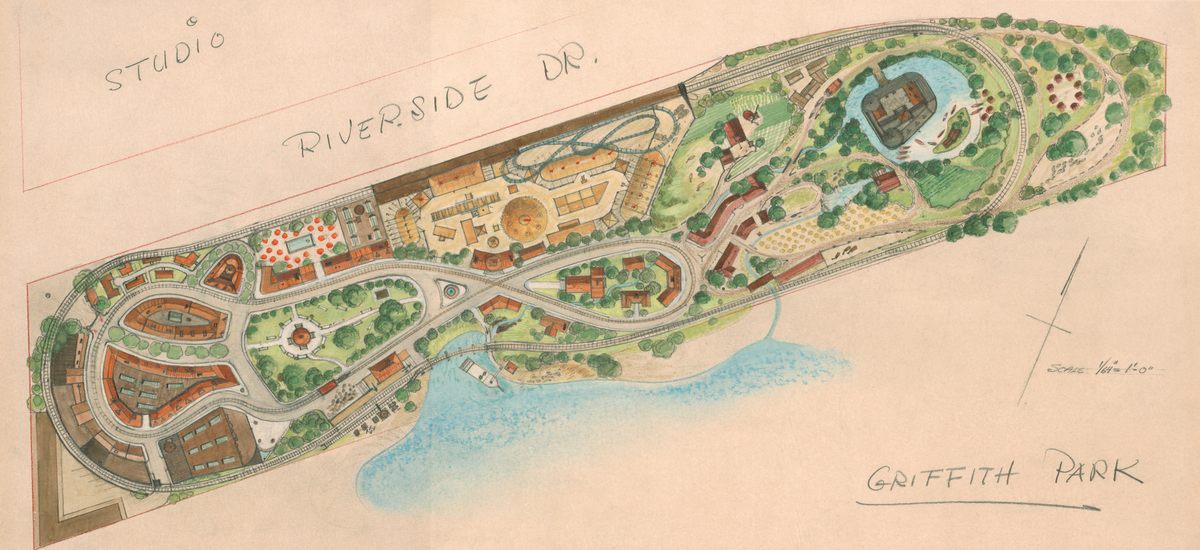

In 1952, he made his case to the Burbank City Council, for a 16-acre site between Griffith Park and his studio in Burbank. They didn’t go for it. “We don’t want the carny atmosphere in Burbank,” Nichols recounts one lawmaker saying. “We don’t want people falling in the river, or merry-go-rounds squawking all day long.” The setback got Disney thinking even bigger.

In 1953, he closed a deal to buy a swath of land in Anaheim, speckled with orange groves and walnut trees, for $4,500 per acre. Linkletter thought it was too remote to draw a crowd, but Disney forged ahead.

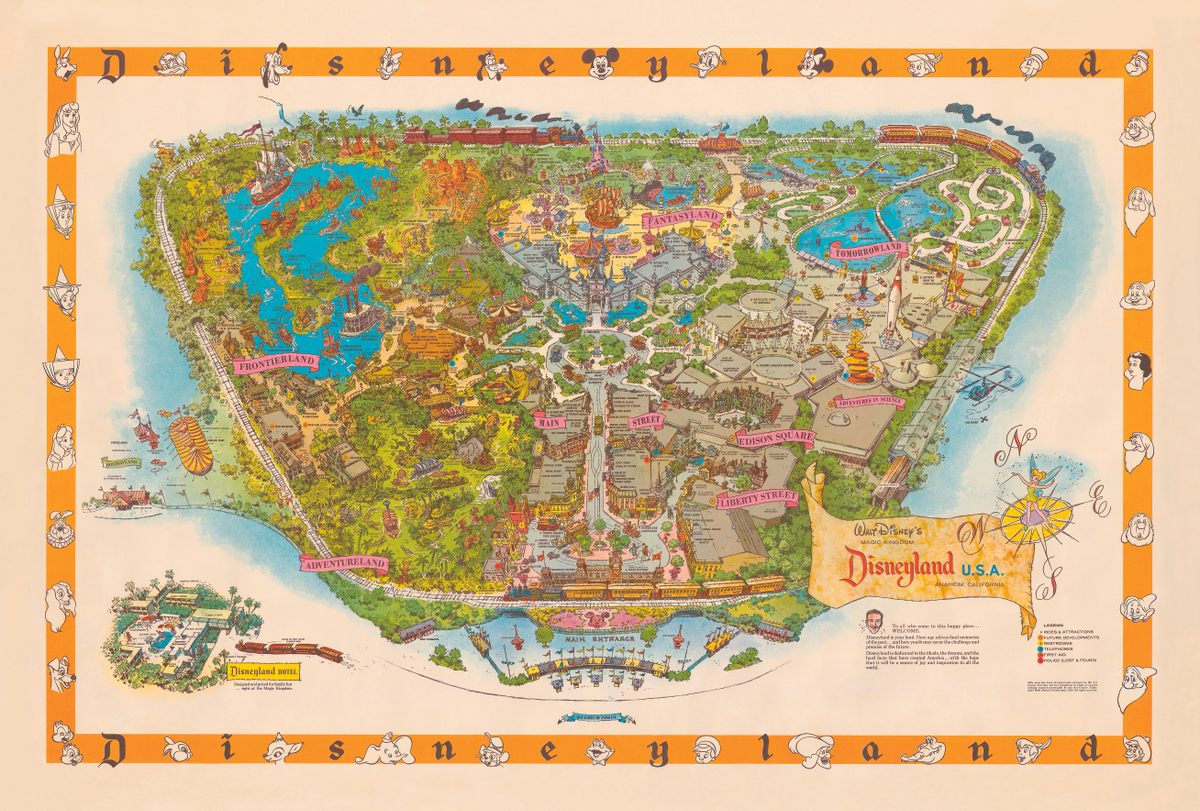

It was like building a new city from the ground up. The site had to be graded. Pipes had to be installed. Clay had to be packed tight over the porous ground, and railroad track had to be laid around the perimeter. When it came to the layout of the park itself, Disney envisioned the hub-and-spoke street grid that underpinned major cities such as Detroit and Washington, D.C. “I want a hub at the end of the Main Street,” he said. “The other lands will radiate, like the spokes of a wheel … Disneyland is going to be a place where you can’t get lost or tired unless you want to.”

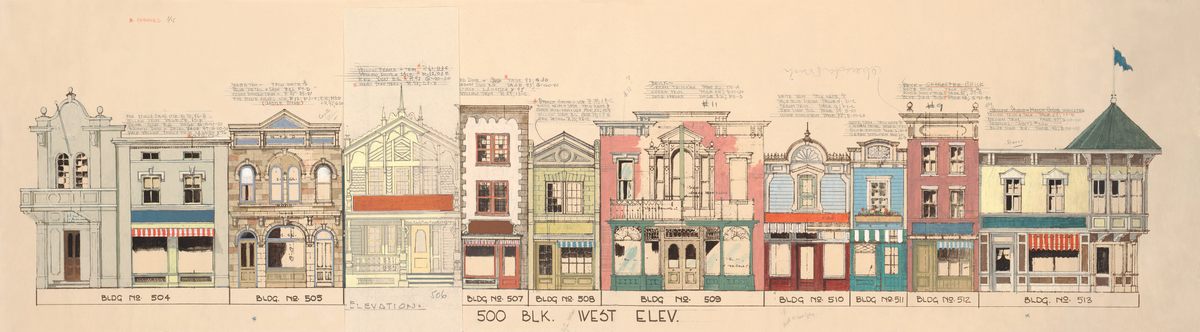

Designers and landscape architects their hands full with models and maps. They diagrammed rides’ interiors and made small models, while Disney recruited artists who had worked on films to paint backdrops. The company retained Renié Conley, who had received an Academy Award for her costume design for Cleopatra, to outfit 10,000 employees. Disney is rumored to have spent more than $500,000—an eye-popping figure at the time—on trees and shrubbery alone.

Then, finally, in July 1955, the visitors came. As many as 15,000 people were invited to opening day, Nichols reports, but roughly twice as many showed up—and a record-breaking 90 million people tuned into a television special about the opening festivities.

If visitors picked up maps to help them navigate the new park, they could see at a glance the payoff of years of planning: the shops and restaurants lining Main Street, the plazas, the wide avenues. Once a few opening day kinks were worked out, the park became the destination it is today. The magic city had finally sprung off the drawing board and into real life.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook