The U.S. Just Expanded the Size of Two Californias

It’s like another Louisiana Purchase.

Did you get a little bit bigger over the holiday season? Well, so did America. You may not have noticed in the pre-Christmas rush, but on December 19, 2023, the U.S. added an area of about 1 million km2 (roughly 386,000 square miles). That’s about the size of one Egypt or slightly more than two Californias.

How did you not notice? Well, perhaps because no shots were fired, no flags were raised, and no actual land was gained. The newest bits of America are all maritime, way out on the high seas. (The more appropriate unit of measurement should therefore be 292,000 square nautical miles.)

Biggest enlargement since the Alaska Purchase

America’s most significant enlargement since the 1867 Alaska Purchase was reported by the U.S. State Department in a terse communiqué, saying it had defined “the outer limits of the U.S. continental shelf in areas beyond 200 nautical miles from the coast, known as the extended continental shelf (ECS),” which the department noted is an “extension of a country’s land territory under the sea.”

“Like other countries, the United States has exclusive rights to conserve and manage the living and non-living resources of its ECS,” the State Department said. “The United States also has jurisdiction over marine scientific research relating to the ECS, as well as other authorities provided for under customary international law, as reflected in the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea.”

The 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS for short) gives coastal states the right to claim an Exclusive Economic Zone (or EEZ) that extends 200 nautical miles from their shoreline. It also allows them to include the ECS: The areas where the continental shelf—the gently sloping underwater extension of a land mass before it drops off to the ocean’s depths—extends beyond those 200 nautical miles.

To date, more than 90 other countries have already claimed their ECS.

- An EEZ should not be confused with territorial waters, which typically end 12 nautical miles out from the shoreline. This is where coastal states have full sovereignty.

- In contrast, countries only have economic jurisdiction over their EEZs. That’s not to be sneezed at: They have the sole right to exploit that zone’s natural resources (fish, oil, minerals, etc.) and to deploy other economic activities (such as wind and tidal power generation) within it.

- An ECS is different still. Rights pertain only to the seabed and the subsoil, not to the water column (including the fish), as is the case in an EEZ.

Although not a signatory to the convention itself, the U.S. recognizes UNCLOS as the basis for international maritime law and in 1983 declared its own 200-mile EEZ. America’s EEZ was the largest in the world. At 3.4 million square nautical miles (11.6 million km2), it is bigger than the land area of all 50 states combined.

Know thy shelf

The ECS adds another 30% to the waters that are under some degree of U.S. jurisdiction. The addition was made possible by a 20-year data-collecting project conducted by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). The project to determine the size of the ECS involved 40 mapping expeditions costing tens of millions of dollars, making it America’s largest offshore mapping effort ever.

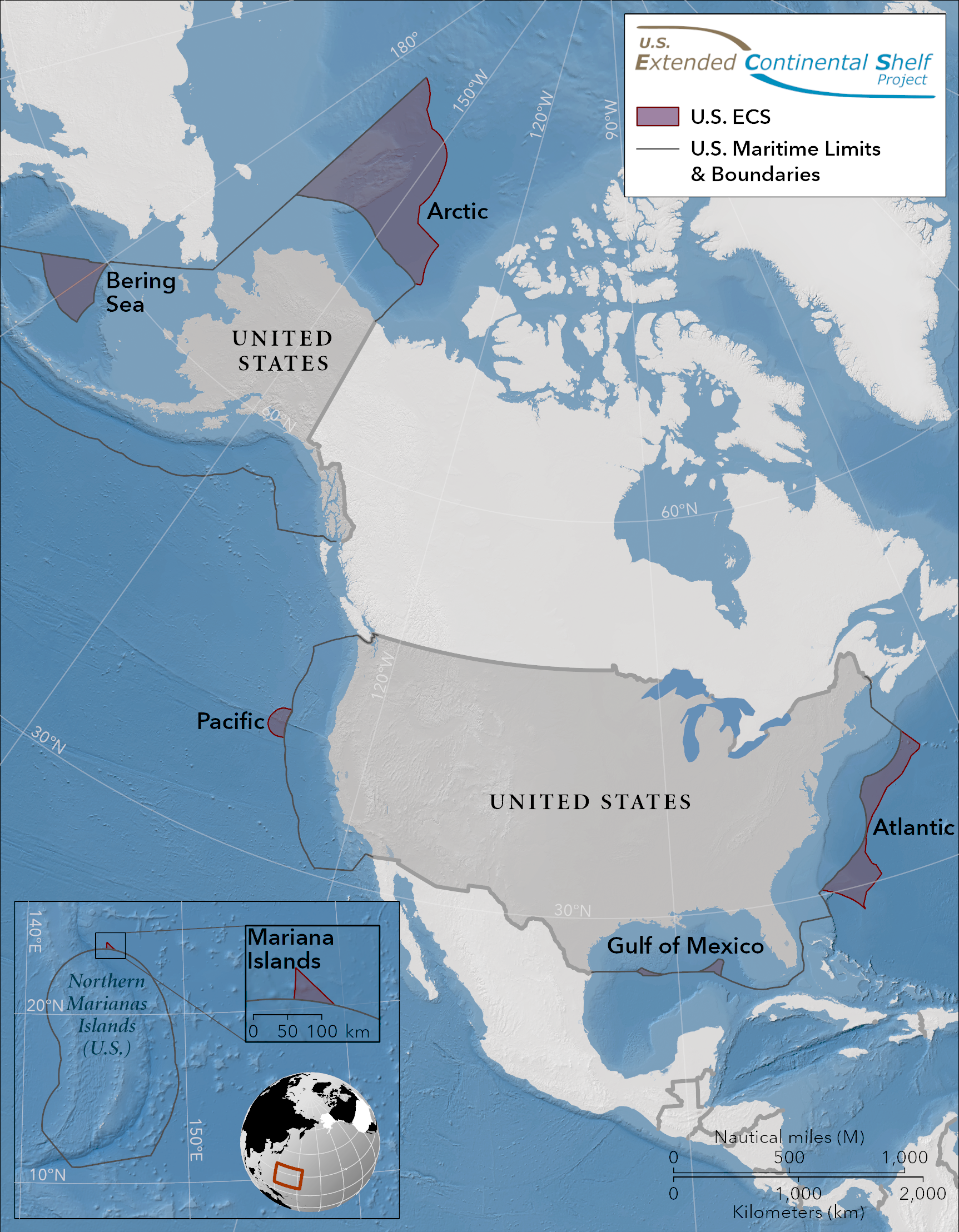

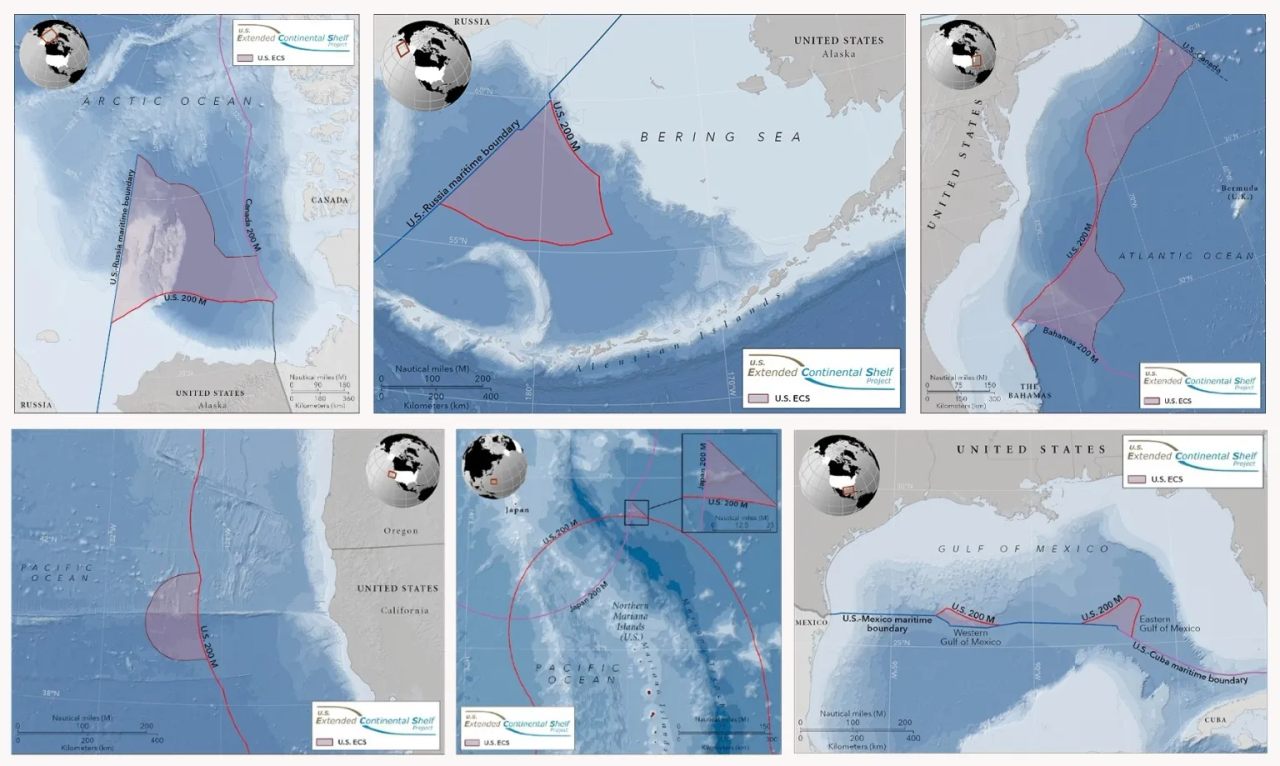

So, where exactly did the U.S. get bigger? The ECS is not one contiguous zone but consists of seven distinct maritime areas.

- Of these, the Arctic ECS, a wedge-shaped slice of the Arctic Ocean north of Alaska, is by far the largest: it comprises 520,400 km2 (151,725 sq nmi), or 52.7% of the total. That’s half an Egypt or one California.

- The Atlantic ECS (239,100 km2, or 69,710 sq nmi) is 24.2% of the total. This slim-waisted band of ocean stretching from the Bahamas to Canada is slightly larger than Romania and slightly smaller than Michigan.

- Plugging a hole in the U.S.-Russia maritime border, the Bering ECS (176,300 km2, or 51,400 sq nmi) is the third-largest addition (17.8% of the total), about the same size as Uruguay or Missouri.

- The Pacific ECS, a bulge off the coast of northern California, is the biggest of the smaller additions (3.3% of the total). Covering 32,500 km2 (9,475 sq nmi), it’s slightly larger than Belgium and about the same size as Maryland.

- Two neighboring patches in the Gulf of Mexico add up to 1.9% of America’s ECS: a larger zone in the east (11,800 km2, 3,440 sq nmi) and a smaller one in the west (6,300 km2, 1,840 sq nmi), together roughly equal in size to Kuwait or Connecticut.

- That leaves the Mariana ECS, a small triangle of no more than 1,300 km2 (380 sq nmi), or 0.1% of the total. That’s about the size of Hong Kong, or one-third of Rhode Island.

Of those seven, the most important chunk is the Arctic one—not just size-wise but also in terms of its resource potential. It’s also a strategic position for the U.S., considering this area will likely grow more important for global shipping as global temperatures rise.

Claims, counterclaims, conflict?

However, unilaterally extending claims on real estate, even of the aquatic kind, may invite counterclaims. While previous agreements with Russia, Mexico, and Cuba exclude the risk of overlap, America’s ECS does intrude on analogous claims by Canada, Japan, and the Bahamas.

Fortunately, the risk of conflict with any of those countries is small. Even though it is a non-party to UNCLOS, the U.S. has stated its claim within the internationally agreed framework of that Convention. That means any disputes are likely to be settled according to the Law of the Sea as agreed by most United Nations member states.

It’s not every day a country manages to enlarge itself with an area the size of two Californias (or one Egypt). Thanks to the strategic location of the Arctic ECS, it may prove as consequential as the Louisiana Purchase. So even though it might have passed you by over Christmas, America’s ECS extension will make it into the history books.

This article originally appeared on Big Think, home of the brightest minds and biggest ideas of all time. Sign up for Big Think’s newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook