Why the USDA Hired Artists to Paint Thousands of Fruits

Researchers and a Twitter bot use them today.

As a child in the mid-19th century, Deborah Griscom Passmore would clamber onto the wide stone windowsill of her ancestral home in Delaware County, Pennsylvania, and paint watercolors of flowers and fruit using the juices from her subjects. Little did she know that one day she would be leading the project to create one of the most beautiful botanical archives in existence.

The National Agricultural Library in Beltsville, Maryland has one of the largest collections of agricultural research in the world. Part of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the Rare and Special Collections houses the USDA Pomological Watercolor Collection. As pomology is the science of growing fruit, the collection consists of 7,500 paintings of fruit and nuts, made between 1886 and 1942. It archives the work of 21 artists: 12 men and nine women. Dozens more created such art for the USDA, but only the works of these 21 are in federal possession, the others being lost to history or held in private collections.

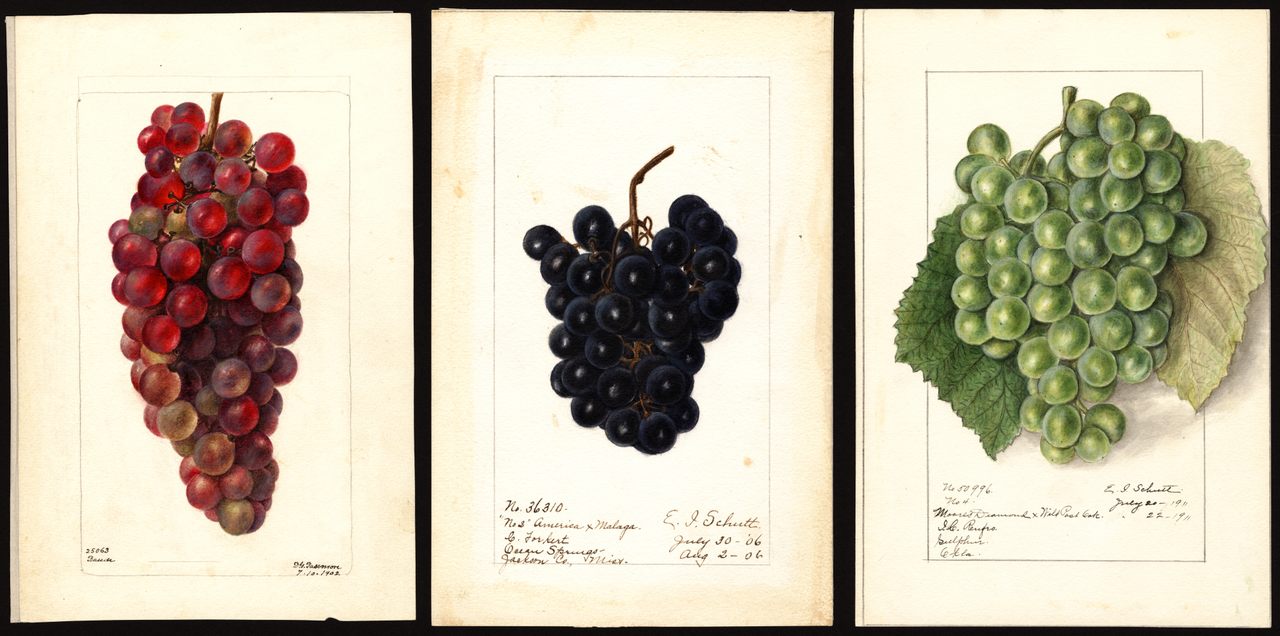

According to Yale historian Daniel Kevles, American horticulturists and nurserymen had long published illustrated prints of their holdings, which included new fruit varieties from experiments with cross-breeding. Identifying and staking ownership over particular fruits was protection against rampant appropriation by competitors, some of whom would sneak into rival nurseries and steal cuttings. At the time, living organisms were considered unpatentable. Without a reliable repository to document specific varietals and store information about provenance, characteristics, and names, fruit innovators were getting cheated out of the rights to their creations, writes Kevles.

Moreover, fruit was big money. In the 19th century, the American fruit industry was growing rapidly, with an annual revenue of between $200 and $300 million dollars. In 1886, the USDA established the Division of Pomology in order to create a national register of plants and fruit. According to one profile of the organization, the mission of the Division was to “document new varieties, publish illustrations, and disseminate research findings to fruit growers and breeders through specialized publications.”

The Division of Pomology issued annual fruit catalogues and bulletins containing the pomological illustrations. Many were depictions of findings from plant explorations and botanical research, as well as artistic records of specimens sent in by growers. The publication of the illustrations empowered growers, as they served as informal trademarks. The Division of Pomology quickly became a resource for orchardists and keepers of nurseries to protect claims to their fruit innovations.

Only two years before the creation of the Division, the future founder of Kodak, George Eastman, had invented the photo film, making photographs easy to produce. At the USDA, though, nobody was taking any chances with this new technology. Still lifes remained the chosen mode of recording and registering fruits. Today, some of these paintings are the only evidence of the existence of lost fruit cultivars, such as hundreds of forgotten apple varieties.

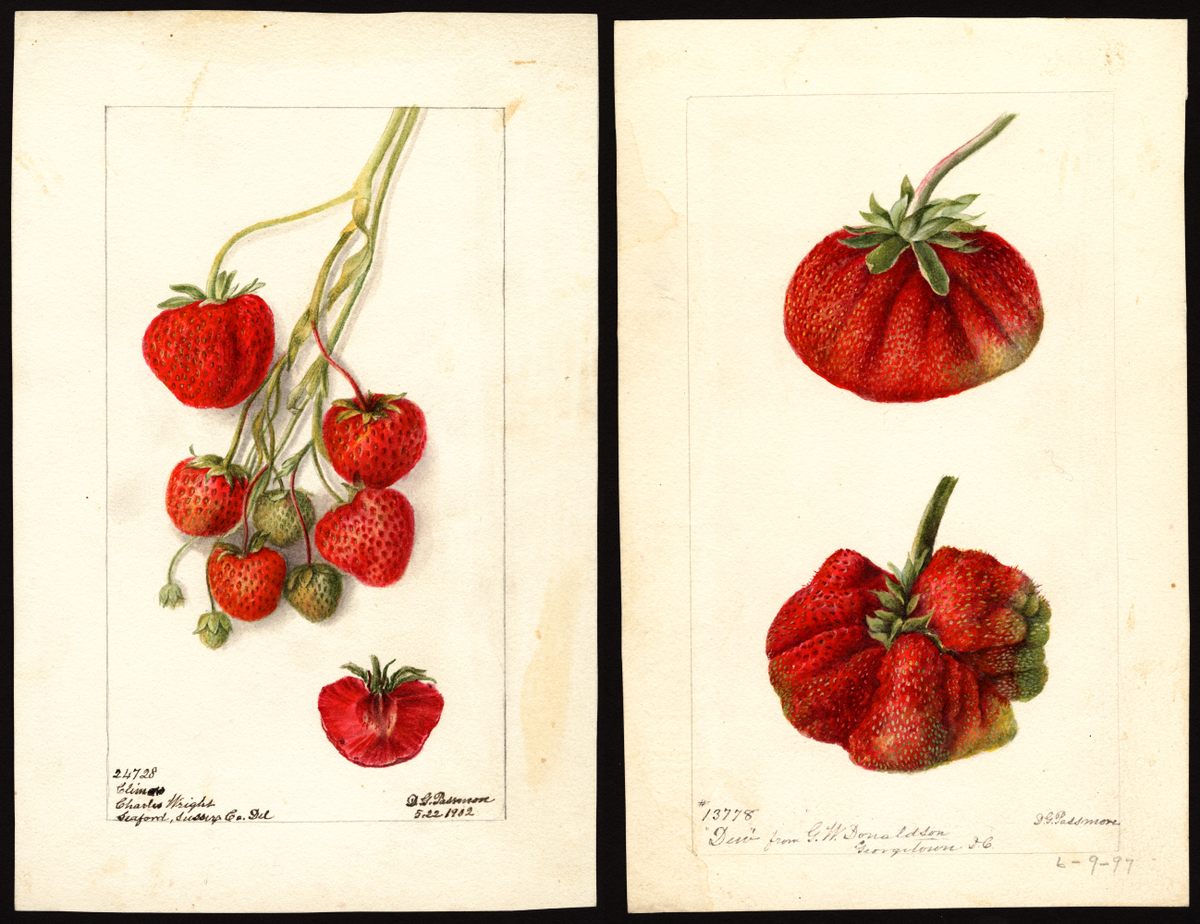

Starting in 1892, Passmore was the principal artist at the Division, a position she held for nearly twenty years. Tables full of strawberries still attached to their vines, luscious grapes, and trays of citrus, mangoes, and sapodillas lay arranged in ornamental display at her desk, ready to be memorialized for eternity on canvas. Passmore earned high praise in the local press (including the Washington Post) for the technical finesse of her works. She painted over 1,500 watercolors during her time at the USDA, making her the artist with the most pieces in the Pomological Watercolors collection. Another artist for the Division was Amanda Almira Newton, granddaughter of Isaac Newton, the first United States Commissioner of Agriculture (not to be confused with the apple-pondering physicist).

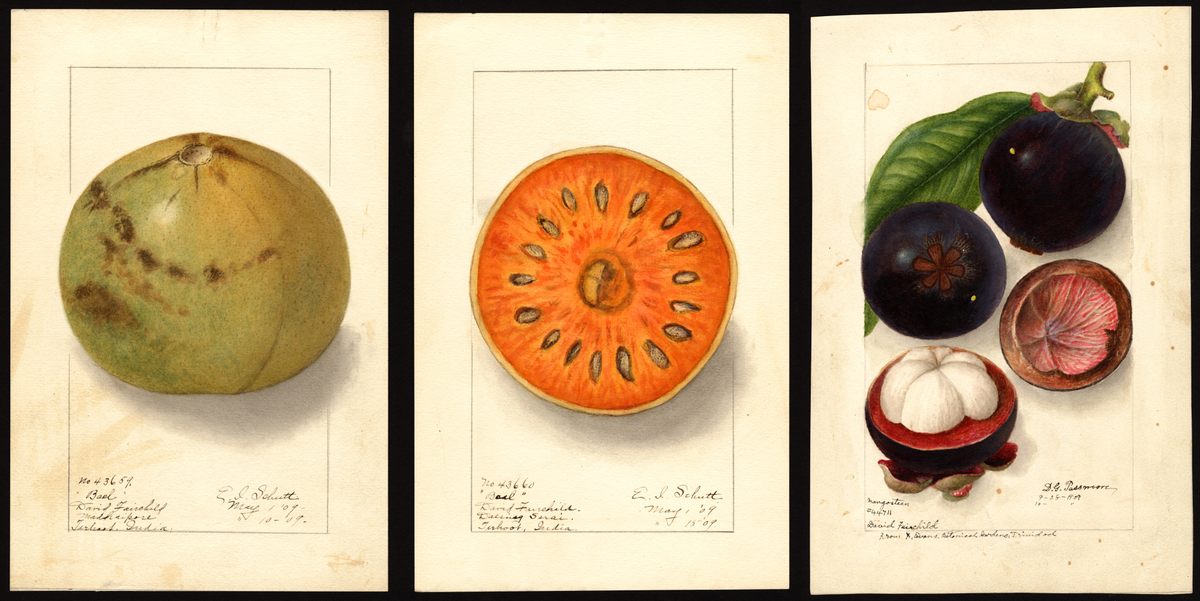

Staff at the Division of Pomology also embarked on plant exploration expeditions all over the world, visiting orchards and vineyards to gather specimens. One plant explorer, David Fairchild, traveled the world on behalf of the USDA, introducing fruits and plants from foreign lands to American soil. Famed for helping photographer and geographer Eliza Scidmore bring thousands of flowering cherry trees from Japan to Washington D.C., Fairchild traveled to over 50 countries and brought such modern food staples as the avocado, kale, and quinoa to Americans. At the Division of Pomology, artists illustrated the bael, a quince-like fruit with a hard outer shell and buttery inner flesh that Fairchild brought from India, and mangosteens he carried from Trinidad and Tobago.

Some of the paintings show visibly bruised or even rotting fruit, in captivating depictions of spoilage. As the official scientific documentation of the Division of Pomology’s work, the artists also needed to paint the effects of post-harvest storage on the fruit in order to inform farmers about perishability. “It was important to document the damaged fruit as well as the perfect specimen,” says Susan H. Fugate, Head of Special Collections at the National Agricultural Library.

While the botanical illustrations at the Division of Pomology served as a database of the fruits of America, they didn’t offer the equivalent of an official trademark for fruit innovators. This formal protection of the rights of fruit breeders came after the establishment of the Plant Patent Act in 1930, which accomplished what the illustrated register couldn’t. According to the Act, anyone who “invented or discovered and asexually reproduced any distinct and new variety of plant” could receive a patent. The Act finally offered patent coverage to living organisms, writes Kevles.

In addition to being beautiful works of art, the Pomological Watercolors offer an enduring understanding of the agricultural landscape of America. In 2011, the watercolors were digitized with a grant from the Ceres Trust, a nonprofit supporting agricultural research. “Our mission from the very beginning has been to preserve these treasures and to provide access so people can know about the collection and both its scientific and artistic value,” says Fugate. But initially, only low-resolution images were accessible in the public domain, and high-resolution images could be downloaded for a fee.

One champion of the watercolors is Parker Higgins, a director at Freedom of the Press Foundation, a nonprofit promoting the constitutional rights of journalists. In 2015, Higgins discovered through a FOIA request that the agency had made less than $600 off the images in the four years since digitization (which had cost $290,000). He wrote to the USDA, which subsequently made high-resolution images publicly available for download. Higgins put them up on Wikimedia, and created a popular Twitter bot, which tweets out a watercolor from the collection every few hours.

In 2016, the lasting research value of the collection was showcased with the publication of the seven-volume Illustrated History of Apples in the United States and Canada, which included over 3,500 images of apples from the Pomological Watercolors. This herculean enterprise on botanical history took its author, Dan Bussey, 30 years to bring to fruition.

For Fugate, the beauty as well as “the science and the power of the illustrations for communication” all contribute to their appeal. But for Sara Lee, an archivist at the Special Collections, the most fascinating part of this collection may not even be the watercolors. Some of the paintings have accompanying wax models, which artists made in the exact weight of the original specimen. “They’re just amazing reproductions, and if, say, there’s an apple with a blemish on the original fruit, the artist will have portrayed that in the wax model as well,” says Lee.

The USDA Pomological Watercolors symbolize a long artistic history of intellectual ownership. They’ve gone from helping to establish the proprietary claims of horticulturists to their current status in the public domain, where they can be the property of anyone with a printer. As both a historical resource and the output of a serene Twitter bot, their charm and beauty endures.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook