Viking Hell Is Just as Metal as You’d Expect

Judged unworthy of Valhalla? Welcome to Helheim.

In 1066, during the Battle of Stamford Bridge a few miles outside York, Vikings and Saxons fought furiously. Legend says that a lone Viking warrior held the bridge—for a time—against the entire Saxon army. Standing in the middle of the bridge and swinging his great sword, he cut down dozens of Saxons before succumbing to his wounds.

As he lay dying, this courageous Viking likely took comfort in the knowledge that, for him, the afterlife would be a place of joy: He could expect to head off to Odin’s Hall, Valhǫll (or Valhalla), and there feast with the gods for all eternity or, according to some sources, be chosen by Freja, the goddess of love, to live in the sweet meadows of Folkvangr.

But what about all those Vikings who did not die valiantly in battle? Diseases and malnutrition were rampant in Early Medieval Scandinavia, as archaeological investigations at Viking burial sites such as Björned in northern Sweden have shown. Both tuberculosis and leprosy were present and likely claimed far more victims than axes or swords. While our understanding of what ordinary Vikings could expect in the afterlife is limited, what we do know is rather bleak.

The Viking belief system was polytheistic and had its origins as far back as the Scandinavian Bronze Age, around 3,000 years ago. But aside from a few images and runic inscriptions found across Scandinavia, most of what we know about Viking beliefs comes from a small number of manuscripts penned in the 13th century. The most famous among them is the Younger Edda, compiled by the Icelandic writer* Snorri Sturluson, who may have received some of his education from the Church, and an anonymous collection of myths and legends contained in the Elder, or Poetic Edda. This means that most of our knowledge of the pagan Vikings’ belief system was curated during the Christian era, often by individuals trying to fit the stories into a Christian worldview, and that the full geographic scope of the Viking world is not represented: It’s unlikely that traditions in 13th-century Iceland were identical to those in 11th-century Denmark or ninth-century Kyiv.

The tales that have survived the edits of monks like Snorri describe the experiences of the Norse families of gods, the Aesir and the Vanir, as well as their traditional enemies, the Jötunn. Amid stories of deceit and trickery, battles and bravery, there are descriptions of the realms through which the Aesir moved easily—but through which humans could generally only move after death.

In the Poetic Edda, a völva, a kind of diviner who, in this case, had died and been reanimated by Odin, states that the universe was comprised of nine such realms: “I remember yet the giants of yore, who gave me bread in the days gone by; Nine worlds I knew, the nine in the tree with mighty roots beneath the mold.” The tree in question is the world ash, Yggdrasil, which connects all the worlds through its branches and roots. There is no overall agreement in the various poems for what constitutes the nine realms, but they certainly included Miðgarðr, the realm of humans, various realms of gods and other beings, and finally Niflheim.

Niflheim was one of the primordial realms that existed even before the gods. It was a place of cold mists, ice, and frost. While there is some variation in the surviving texts, most agree that an area within Niflheim became a place for the dead, thanks in part to the trickster Loki, who had three children with a Jötunn woman. The first two were monsters: the sun-swallowing Fenris wolf and the world-encircling serpent Jörmungandr.

The third of Loki’s children was not a terrifying monster but a gloomy, stern girl. One half of her face was healthy, the other blue and rotted. Odin cast the child into the cold world of Niflheim and gave her dominion over all those who did not die honorably in battle. Her name was Hel, and the area of Niflheim where she reigned would be known as Helheim.

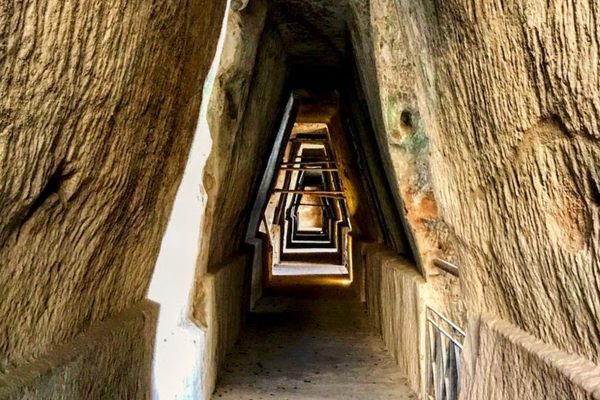

Those who died off the battlefield reach Helheim by traveling for nine days along a road in total darkness. First, they would reach a deep and cold river, called Gjöll. Across it was a golden bridge guarded by a fierce woman known as Móðguðr, or Modgud. She was tasked with preventing the dead from recrossing the bridge, back into the world of the living. Beyond the bridge, the dead had to travel both northward and deeper beneath the ground to reach Helheim.

There they found a wall and gate, and beyond it Hel’s hall, Eljudner. It was not a pleasant place: “Her hall is called Sleet-cold,” according to the Younger Edda. “Her dish, Hunger; Famine is her Knife.” Hel slept in a bed called Disease surrounded by bed hangings known as Gleaming Bale. For those who had sinned in life, especially oath breakers, rapists, and murderers, an even worse fate awaited: the hall of Náströnd, made from the entwined bodies of venomous serpents. The serpents would spit a never-ending flow of burning poison on the sinners. To add to the punishment, their bodies would be chewed by the feathered dragon Níðhǫggr.

In many ways, Helheim was the complete opposite of Odin’s hall, Valhǫll. Valhǫll was a place of light and plenty, far from the cold misery of Helheim. But the dead of Helheim would not stay forever in their gloomy realm. At Ragnarök, the end of all things, the dead would board the ship Naglfar, built from their toe- and fingernails. According to the unnamed völva in the poem Völuspá, with Loki as captain and the dead of Helheim as crew, Naglfar would join in the final great battle, which would claim the lives of all the gods and, through fire and blood, make the world anew.

*This article previously stated that Snorri Sturluson was a monk. He was a writer and politician.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook