In Venice, Carnival Is a Visual Feast of 18th-Century Splendor

Every February, millions of people flock to Venice for Carnival, but few know the festival’s true origins.

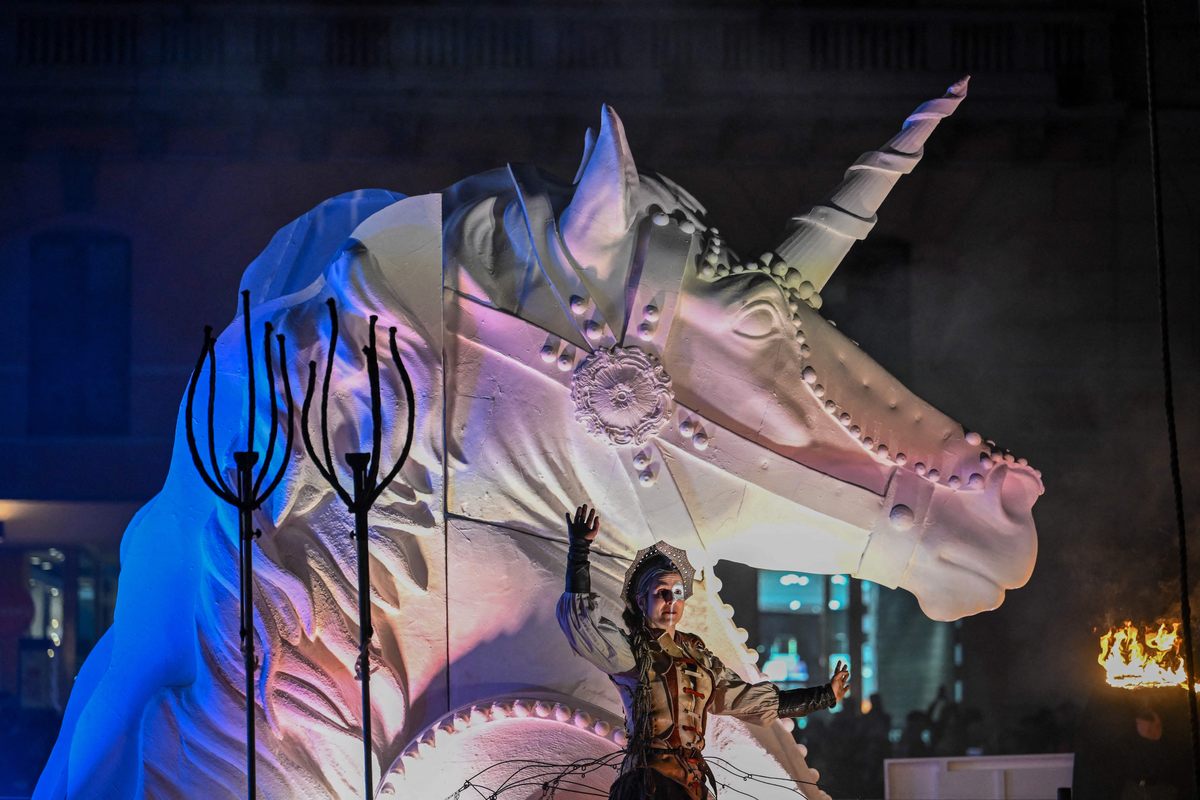

In Venice, Carnival begins by boat. Thousands gather, lining the banks of the Grand Canal. Some wear masks with elongated noses and mischievous expressions. Others don elaborate 18th-century gowns accessorized with powdered wigs and strands of pearls. Then, as darkness settles over the floating city on the first night of Carnival, the distant strains of an Italian opera drift through the air. All heads turn towards the music emanating from further down the canal, the soprano’s aria growing louder and louder. Until, finally, they see it—flames erupt from the front of a massive floating stage. Carnival has begun.

Following the opening night parade, usually held in early February, Venice’s Carnival season officially opens. For the next two and a half weeks, masquerade balls, street shows, mask and costume competitions, and parades transpire almost daily in the city. Every year, on the day after the opening parade, a fleet of traditional Venetian vessels sails into the Grand Canal, Venice’s main waterway, following a 22-foot-long, papier-mâché rat. At the end of the procession, the rat, which has become a symbol of the historic port city, bursts open, releasing dozens of colorful balloons. And that’s just the beginning of the whimsical, magical world of Venice’s Carnival, which has attracted masked revelers for centuries.

The origins of the Venetian Carnival are murky. Legend has it that the first Carnival was held in 1162 following the Republic of Venice’s victory over Aquileia, a neighboring coastal town to the north. At the time, Venice was only a lowly township, notes historian Gilles Bertrand of the University of Grenoble Alpes in France. In medieval Catholic Europe, Carnival became a time for partying, excess, and debauchery before the restrictions of Lent. The Venetian Carnival was a time to disregard societal restrictions placed upon class and gender, and people would often wear masks and costumes to disguise their identities. As the Republic of Venice grew into a major European power in the 15th century, Carnival became a time for the Republic to show off its wealth to the rest of Europe, writes Bertrand. The aristocracy increasingly controlled the celebrations, and by the 18th century, European elites and royalty often attended the spectacle. By the 1700s, Venice had become the playground of the rich and powerful.

But in 1797, the party was cut short. Napoleon Bonaparte conquered Venice and the Republic of Venice lost its independence. The city eventually landed in the hands of the Austrian Empire. For a time, Austrian leaders banned Carnival along with “entertainment deemed the most threatening to public order,” writes Bertrand. In the shadows, a reduced Carnival continued to trudge on in the 19th century and, in an even more reduced form, in the 20th—until 1980 when the Venetian Carnival returned. Funded by an Italian government looking to drive tourism, the 1980 festival featured theatrical shows and events directed by illustrious European theater artists.

Today, Venice’s Carnival is a blend of 18th-century nostalgia and 21st-century consumerism. Though the festival has taken on many shapes throughout its long history, there’s still something enchanting about a floating city filled with people behind masks. To celebrate Carnival, Atlas Obscura has selected some of our favorite images from the 2023 celebration, which began on February 4 and will reach its dramatic conclusion on Shrove Tuesday or Mardi Gras, falling this year on February 21. Wherever you may be this Carnival season, these images will transport you to the entrancing world of Venetian costumes and magic.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook