Videocassette Dating Let Singles Fast-Forward to Love

Long before Tinder, singles put themselves onscreen for love.

Imagine: it’s 1976, and you’re a busy professional living in LA. You’re also single, and looking, but it isn’t working. You’ve been on dozens of first dates, and gamely accepted every introduction that’s come your way, but that spark—that someone special—keeps eluding you.

Then one day, tucked among your magazines and bills, you find a strange piece of junk mail. “No more blind dates!” it reads. Intrigued, you head to the address, a “Membership Centre” in Westwood Village, where you’re greeted warmly, ushered to a seat and the lights dim.

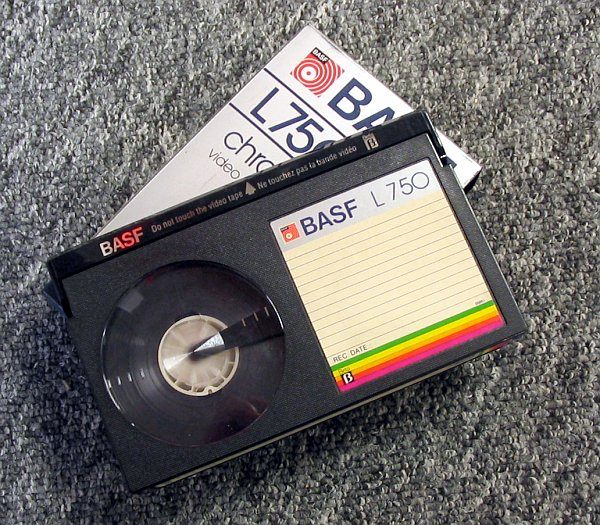

These days, as everyone knows, you can swipe through a city’s worth of potential dates while waiting in line at the bodega. But for decades, if you wanted to gaze upon a plethora of eligible singles, you had to go to a repurposed office building during open hours and watch them flicker by onscreen, spooled through Sony Betamax SLO-320s. Welcome to the age of video dating.

Betamax cassette tapes, an early example of the technology that enabled video dating. (Photo: Tomasz Sienicki/CC BY-SA 2.5)

The 1970s was not only a time of sexual freedom, but also relationship tumult. Thanks to new laws and evolving sexual mores, divorce rates were climbing. Around the same time, VHS and Betamax tapes became widely available, enabling people to record and watch themselves without needing to invest in prohibitively expensive equipment.

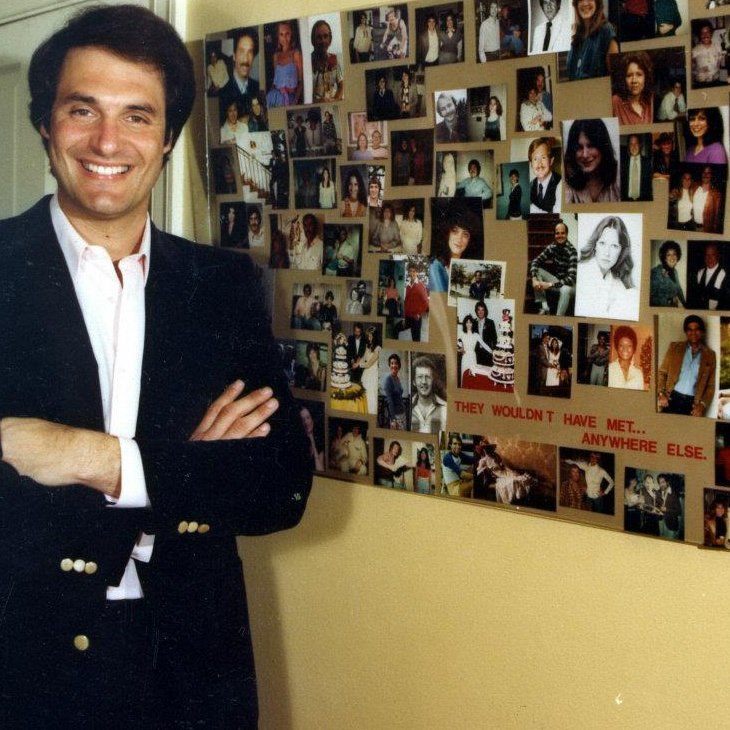

After spending a dinner party listening to his cousin lament how difficult it was to meet people, a young videographer named Jeffrey Ullman put two and two together. He borrowed seed money from his parents, did a bunch of research into the psychology of attraction, and created the first video dating company, which he christened Great Expectations. According to company lore, they launched on Valentine’s Day, 1976.

“Single people” are a tricky demographic to pinpoint, so Ullman took a scattershot advertising approach, taking out radio ads, bombarding local reporters with press releases, and—most effectively—sending out pounds upon pounds of well-targeted junk mail. Once seduced, prospective clients would head to the Great Expectations offices, where—after they paid one-year membership dues of about $200—the real magic began.

“We didn’t call them customers or single people, we called them members,” says Ullman. “And we didn’t call them offices, we called them Member Centres.” These Centres were staffed by friendly customer service representatives, including Ullman’s mother, who worked there for years. They were decorated almost exclusively with enormous photos of happy couples—eventually, ones who had actually married after meeting through Great Expectations. “They were huge, like four by six feet,” says Ullman. “Candid shots.”

New recruits would first fill out a “Member Profile,” which asked for your hair color, height, “religious/racial dating preference,” and so on. Then they would enter the “interview room,” which was dressed up as a generic office set—bookshelves, plants, pleather chairs. A Great Expectations employee would come in, click on a hidden camera, and begin gently grilling you.

Ullman considered this interview, which he called the “Talk Show,” the heart of the Great Expectations process. “You have to show as much as possible the essence of the person,” he says. “If a picture is worth a thousand words, what do you think video with audio is worth—ten million words?”

A young Jeff Ullman, backed by early success stories. (Photo: Jeff Ullman)

Some questions were the sort usually reserved for late-night reveries: “What do you want to be when you grow up?” “What is your secret dream?” Others, by design, were a bit harsher. “I’d say to you, “You’ve got five kids, and you live way out in the suburbs. now I don’t mean to insult you, Ethel, but how datable are you?’” recalls Ullman. “Now that’s putting Ethel on the spot! But if you’re John watching Ethel, that’s on your mind. You open an objection and then you answer it.”

After squeezing acceptable answers out of you, the employee would show you the resulting five-minute tape. Then they’d file it away, and you’d go home and wait. If all went well, within a few days, you’d start getting postcards. “Please come in for a viewing,” they’d read. “You have been requested by Greg.” At that point, you’d return to the Great Expectations office to read up on Greg, and, if your interest was piqued, to view his tape.

Then and only then—when each of you had vetted the other—would the company brush its hands off, inform you of each others’ contact information, and step back. Depending on each party’s enthusiasm and availability, this swipe-right process could take anywhere from days to weeks. (If you decided to turn someone down, they’d be informed, delicately, that you were “not available.”)

To hardened Tinder users, this probably seems tame, even quaint. But at the time, video dating was considered somewhat scandalous. Ullman spent a lot of time reassuring reporters that it was both safe and morally sound—after all, he argued, what ne’er-do-well or wannabe adulterer would willingly “put his face on a video tape for the police to see?”

Reputation management was more difficult. “It was really stigmatized at first,” says Moira Weigel, author of Labor of Love: The Invention of Dating. “A lot of articles in the late ’80s and early ’90s would say ‘It’s not just for losers anymore!’ So you can tell everyone definitely thought it was for losers.”

But others were great fans. “Where else can you have access to so many potential companions without spending every waking hour hustling and having to go out on dates that may turn out to be nightmares?” wrote Harlan Ellison, an essayist who watched dozens of video profiles while researching a 1978 article for Los Angeles magazine. ”Clients are delighted by the novelty of being able to choose someone out of a book, watch them on a TV screen, and then have a neutral party find out if they want to date them, without being rejected face-to-face,” gushed a 1981 UPI article, quoting one woman who said that “looking at the tapes was like a kid going into a candy shop.”

A scene from “Not So Great Expectations,” an episode of the sitcom Ellen that spoofed video dating companies. (Screenshot: Youtube)

By 1985, Great Expectations had 17 franchises, and was pulling in millions of dollars. Competitors got in on the game, offering local flavor. “You definitely see the dynamic of niche-ification that happens with dating apps now. By the mid-’80s you have ‘Mazel Dating for Jewish Singles,’ or ‘Soul Date a Mate,’ which is this LA-based one for African-Americans,” says Weigel. “There was even one specifically for people with herpes in D.C..”

Then, of course, came the internet—the greatest niche-ification machine of all time. Match.com, the first dating website, went online in 1995, and was quickly followed by JDate, eHarmony, and Ashley Madison. Most smaller video dating sites shuttered, unable to compete with these new offerings’ efficiency and (relative) low cost. (But not before playing a pivotal role in Cameron Crowe’s 1992 opus, Singles.) Ullman sold Great Expectations in 1995, too, and within a few years, its new owners had shut it down.

Our current technological climate seems like the perfect place to resuscitate video dating—after all, we’re already curating our Snapchat stories 24/7. But people haven’t really seemed that interested. When YouTube launched in 2005, it was originally supposed to be a dating website—until its founders discovered that people wouldn’t post dating videos to it even if they paid them. Take in the vulnerability on display in videos like, say, this infamous montage, and the misgivings become more clear.

But Weigel thinks there may be room for it in the future—if not for a Vine-Tinder hybrid, then something that looks a bit more like Great Expectations. “We’ve seen, in the past few years, this return to matchmaking—growing numbers of people who want humans to matchmake them, because they’re sort of fatigued with apps,” says Weigel. “Video dating felt more like matchmaking.” There was a person in the room with you, asking you questions about you as though they really cared. Even if you never got a date, at least you got to talk to them.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook