Why 1920s L.A. Went Wild for an 19th-Century Scottish Novelist

Walter Scott wrote fantasies about medieval Saxons—just the thing for Jazz Age Angelenos.

On a hot November day in 1926, a 13-year-old boy dressed as the Pied Piper led more than 1,000 children not out of town, but to the Central Library of Los Angeles. He marched at the head of a parade held to celebrate the opening of the children’s reading room. The piper, who had earned his spot by winning a city-wide writing competition, was a burgeoning Japanese-American poet possessed of a great talent and a great name: Ambrose Amadeus Uchiyamada.

From the sun-scorched streets of America’s newest metropolis, the children, many dressed as storybook characters from throughout history, were invited through the doors of the Art Deco library. On the lower level, they suddenly stepped into the Middle Ages. The children’s reading room was fashioned from reinforced concrete, like the rest of the building, but its hulking beams were painted to resemble those of an oaken medieval hall. On the walls were scenes of knights and ladies, minstrels and friars. All came from the 1819 novel Ivanhoe by Scottish writer Walter Scott.

Ivanhoe was both an apt and an odd choice for 1926. It was apt because Scott, who lived from 1771 to 1832, penned historical tales of chivalry, romance, and derring-do so popular that settlers and developers named towns, streets, and neighborhoods for him throughout the English-speaking world. (If you live on Waverly Place in Manhattan or in Waverley, Tasmania, you live somewhere named for a Scott novel.) It was odd because by the 1920s Scott mania had largely faded. Yet it remained strong in Los Angeles for two very different reasons. For some, Scott’s work provided an appealing link to a familiar but imagined past. For others, it promoted an ideal of Saxon virtue that was under threat in the jazz-age metropolis. The Central Library’s “Ivanhoe room” was born of both fantasy and anxiety.

Los Angeles’ habit of taking inspiration from the novels of Scott belongs to a tradition that began in the 1830s. According to Ann Rigney, author of The Afterlives of Walter Scott, naming things for the characters and settings of his stories was a way for European immigrants to make sense of an American landscape whose history they didn’t know and couldn’t understand.

“There was a hunger for history and a landscape that seemed to be lacking in it,” says Rigney. “And so what you have is what I call mnemonic colonization, the idea that you can import your stories.”

Los Angeles, which would later specialize in importing stories, began early by marketing some of its first suburban developments with storied names like “Ivanhoe” (now Silver Lake), “Waverly” (after another of Scott’s novels, now University Park), and “Melrose,” which is bisected by a bustling restaurant- and entertainment-filled avenue of the same name. “If thou wouldst view fair Melrose aright / Go visit it by the pale moonlight,” wrote Scott.

Good advice for visiting Melrose Abbey in 1806 and, perhaps, for visiting Melrose Avenue today.

After the 1880s, Los Angeles’ Scott fascination continued with the Abbotsford Hotel (named for Scott’s grand home), the neighborhood of Montrose (another Scott novel), and the Rowena Reservoir, named for the future wife of the crusading knight, Ivanhoe.

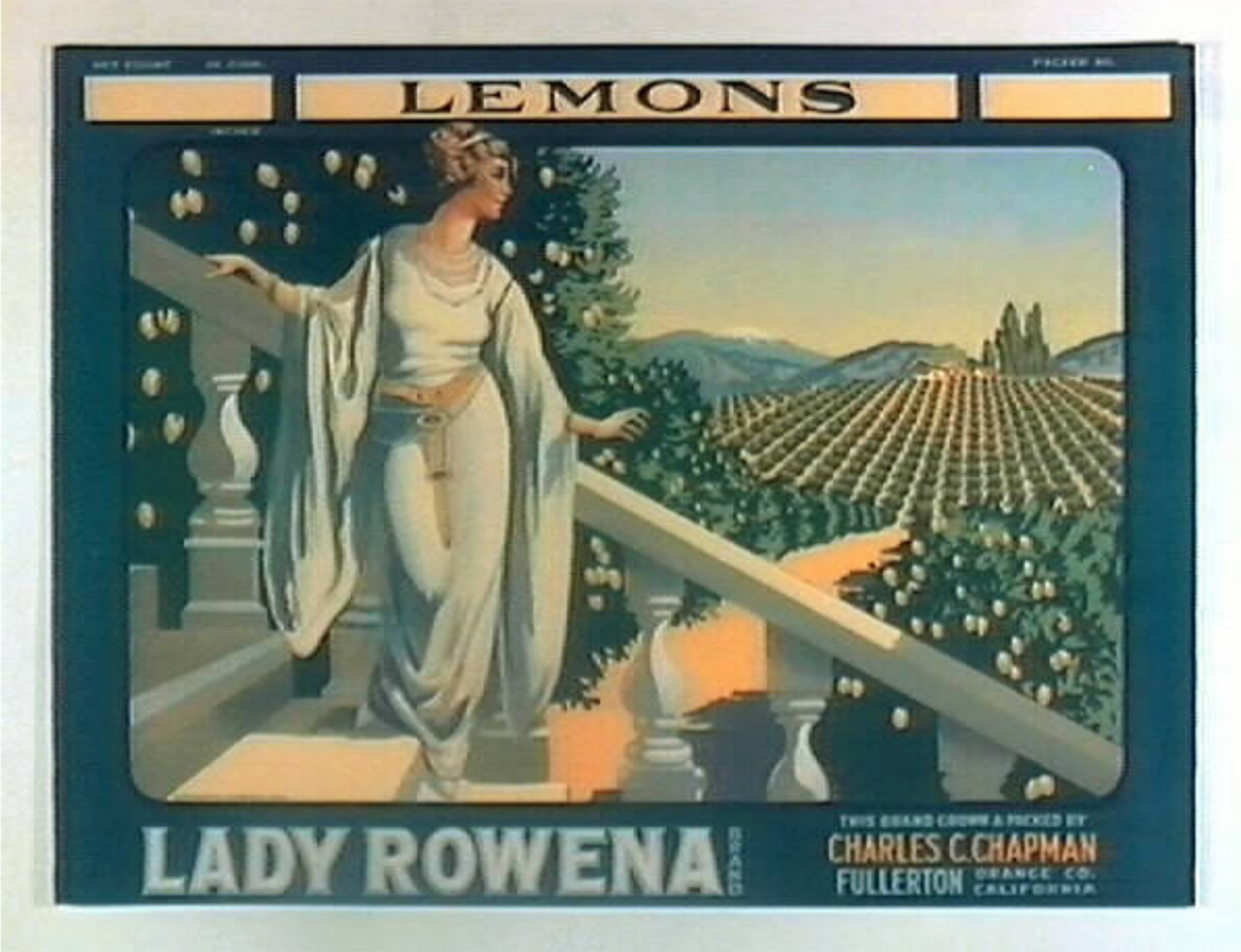

She was a popular figure in Los Angeles. In addition to the reservoir and a nearby avenue she gave her name to a brand of lemons grown and marketed by Charles Chapman, the citrus baron who used his fortune to transform California Christian College into Chapman University. A lavish 1920 crate label depicts Rowena draped in medieval garb surveying her SoCal orchard. Her voluptuous appearance may not suggest it, but Scott’s Rowena had many virtues to recommend her to the deeply religious Chapman. Christian, Anglo-Saxon, and rather dull, Rowena embodied a WASP-y entitlement characteristic of Los Angeles’ ruling class in the first two decades of the 20th century.

In that era, “[t]here is an assumption and presumption that Los Angeles will be the capital of what people will quite self-consciously refer to as Anglo-Saxon America,” says William Deverell, director of the University of Southern California-Huntington Institute on California and the West. “I suspect the Scott craze is tied at least in part to that project.”

The 1920s was the decade in which that project would find itself in danger. Nearly 600,000 newcomers doubled the city’s population, and not all of them knew their Scott. A new cosmopolitanism was taking root and some panicked Angelenos voiced their displeasure. Radio evangelist “Fighting Bob” Shuler broadcast shockingly bigoted harangues twice a week. A literature professor warned that civilization would be destroyed if it turned against the “surer faith” of Scott. Charles Chapman, while not hawking Lady Rowena’s lemons, expressed his concern in more muted tones.

“We have great problems here to be solved and as our city grows there will be more,” he said in 1923. “We want to build a truly American City here.”

The children’s reading room provided an opportunity to start young readers off right with Sir Walter. “It is hoped that every child in Los Angeles will become acquainted with the new Ivanhoe room,” wrote the Times when it opened. “The murals bringing to life the characters from Ivanhoe, the ceiling painted in imitation of an old Norman beamed ceiling … make up a room which is an inspiration for small book-lovers.”

Not all city projects had the same ambition as the Central Library, but were connected to Scott all the same. A new bridge built on Franklin Avenue in 1926 was designed in a Norman gothic style, reminding citizens of Silver Lake that their neighborhood used to be called Ivanhoe. Paramount Pictures built an apartment complex near their lot in 1930 and called it the Ravenswood, the ancestral home of Scott’s tragic hero Edgar in The Bride of Lammermoor. It attracted the likes of Mae West, who lived there until her death five decades later. Built in a stripped-down Spanish-revival Deco style, the Ravenswood’s only Scott-like feature is the faux-gothic lettering on its sign. By 1929 a Scott name might have only the gauziest connection to his novels.

“[Naming things for Scott becomes] more about the commercialization and commodification of culture by developers looking for quick names,” says Rigney. “They come up with a Scott name because it sounds chic and it sounds old.” A name like Ravenswood represented drama and grandeur—the pure fantasy of Scott’s world rather than its political import.

Scott’s status as evangelist of Anglo-Saxon identity hadn’t succeeded and so, on the eve of the Great Depression, he was instead celebrated as a minor prophet in that most American of religions: making money. On New Year’s Day 1928 the Los Angeles Times published a short piece about how Scott faced a mid-career bankruptcy. “Instead of going under in a collapse and crying about it, Sir Walter tightened up the hunger belt a few notches, took his good gray goose quill pen in hand, and started in on the immortal Waverly novels.” No significant buildings would be named for him after the 1930s.

Today, Scott’s impact on the city is sometimes hard to spot. Children no longer escape into chivalric books surrounded by his murals: The library’s children’s reading room has moved upstairs. The Rowena Reservoir has been closed to the public for years. And the Norman-style bridge that once grandly welcomed drivers to the Ivanhoe neighborhood never picked up a Scott name at all. To locals it’s known by the name of another bard of historic tales whose oeuvre, unlike Scott’s, never fell out of favor. They call it the “Shakespeare Bridge.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook