The Raw Ore Centerpieces That Turned Grueling Labor Into Cutesy Dioramas

Handsteins were beloved of 16th-century princes because they affirmed the social order.

In the 16th century, whenever a dramatically contorted chunk of ore emerged from a mine in Central Europe, the nearest prince would often lay claim to it. Favorite goldsmiths were then commissioned to transform the rough find into an improbable dollhouse-like sculpture known as a handstein, meaning “hand stone”—an artwork that was meant to be admired while held aloft.

Well into the 1700s, samples like these, of minerals as rarefied as acanthite and aragonite, were set on fluted or scalloped pedestals made of precious metals. Brightly colored statuettes and buildings were tucked into the crags. Biblical figures, steepled churches, and palaces would adorn the miniature peaks, while along the bases, miners were depicted trundling through forests, maneuvering in tunnels and operating machinery in rustic huts. Mini-narratives played out in the details. Some handsteine (the plural form) also served as dining table centerpieces or desktop accessories, equipped with water spouts and vessels made of metal, glass, or crystal that could contain condiments, sweets, or ink.

To modern eyes, handsteine can be unsettling—raw rock, almost cutesy craftsmanship, lavish gemstones, depictions of grueling labor, and sometimes dramatic moments from the Old and New Testaments. The miner figurines at times resemble Bond minions or Disney dwarves, blithely going about their workdays while villainy and bloodshed unfold above them. And, as for the handsteine that multitasked as tableware, why would anyone want to eat food served from boulders depicting scenes of crucifixions and hazardous workplaces?

For the era’s laborers, as well as consumers of luxury goods, however, the paradoxes made sense.

Ana Matisse Donefer-Hickie, a research associate at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, analyzed handsteine while working on the Met’s 2019–2020 exhibition, Making Marvels: Science and Splendor at the Courts of Europe. In her catalog essay about a Hungarian handstein from the German Mining Museum in Bochum, she explains that mine owners and operators considered the minerals “evidence of the riches bestowed on them by God.” The Bochum artifact is crowned in a miner figurine, made of silver, brandishing his tools and holding up a glass dish etched with scrollwork patterns. Donefer-Hickie writes that handsteine’s industrial and religious imagery, displayed on natural wonders from below ground, would have suited the era’s concept of “the connection between the macrocosm of the heavens and the microcosm of the mine.”

The Met show was a rare appearance of a handstein in the United States, Donefer-Hickie points out. Few have been acquired by American institutions; their surreal and at times macabre quality has not made for mainstream appeal among the philanthropists who have helped compile the nation’s major art collections. Only a handful of handsteine have ever surfaced on the market, and many remain in or near their original palace homes. They are deemed too fragile to travel much—given their varied materials and intricate surfaces, they are vulnerable to airborne pollutants, shifts in temperature and humidity, and vibrations. (How wonderfully ironic, of course, since they originated in and represent sites where men in minimal protective gear blasted through rock at great personal peril.)

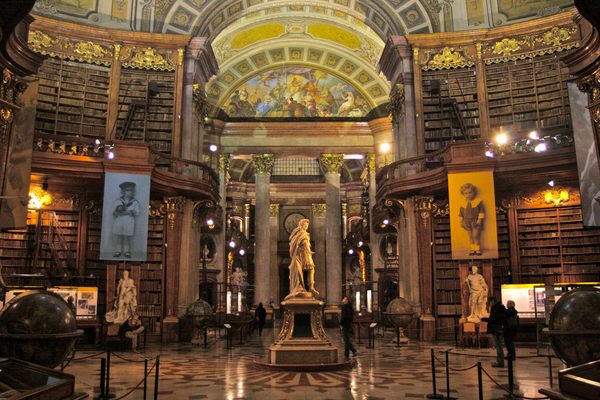

The world’s largest handsteine collection, numbering about 36, belongs to the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. Goldsmiths created them for generations of Habsburgs, from mines throughout the dynasty’s lands. The sculptures would have reminded the rulers of their power over natural resources and hardworking subjects. On some Habsburg handsteine, the coiled silhouettes are reminiscent of Chinese scholars’ rocks. Others are caked in tentacles and jagged protruding crystals. The occasional coconut shell and glass dragon are also in the media mix. The mining equipment depicted, including steam engines, ladders, and winches, represents the latest innovations among Habsburg engineers.

In 2016 and 2017, British artist and writer Edmund de Waal included handsteine in an exhibition at the Kunsthistorisches, During the Night. He was given free rein to select objects from various museum departments. In an essay about his selection process, he explains that he set out to map “the unsteadiness of things,” and focused on bringing out works with “strange potencies.” He compares the tiny saints in the handsteine crevices to amulets warding off the dangers of mines: “places that give way under you, damp and noxious airs and gases that make you sleep. There are seams that offer riches but are false.” He interprets the little pathways carved along the rocky undulations as escape routes. They provide a kind of infrastructure, he writes, for “the landscape of anxiety.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook