The ‘Ninja Diet’ Prioritized Fortitude, Stealth, and Eliminating Body Odor

Understanding what shinobi ate, amid a stew of myths and misconceptions.

The truth about ninjas is as slippery as its subject. These mysterious assassins, sometimes referred to as shinobi, lived lives so inscrutable that the line between history and the fiction they inspire is irremediably blurred.

Though the specifics sometimes differ, ninja experts usually agree on a few common facts: Secretive guerrilla fighters are said to have lived in Japan’s mountainous Mie Prefecture between about 1487 and 1603. During a century of considerable military strife, they are believed to have been for-hire killers who used highly specialized, secretive techniques. Yet even these details, writes scholar and military historian Stephen Turnbull, who has published extensively on ninja culture and history, are hard to prove. Still, he doesn’t believe they are a total fabrication. “All invented traditions have a basis in fact,” he writes, “no matter how tenuously the links may be made between the developed tradition and recorded history.”

A few decades after ninjas are said to have lived, historians and storytellers began writing extensively about them—who they were, what they did, and how they ate. Various accounts describe how they avoided smelly foods (to better sneak up on enemies), restricted their diet to remain agile, or even used food to send secret messages. A vivid picture emerges of ninjas and their diets—though how much of it is based on the real medieval fighters is near-impossible to say, if they existed at all. (Turnbull, for his part, believes that even the earliest conceptions of ninjas are an amalgamation of “genuine belief in a unique local expertise that was bolstered by folk memories and old soldiers’ tales,” as well as an active desire to believe in an appealing military fantasy.)

Modern depictions of ninjas usually portray them as mythic, pyjama-clad figures, scurrying around in the shadows. Yet the earliest accounts, which are most likely to approximate the truth, suggest they were essentially farmers—a half-agricultural worker, half-samurai, who ate like his rural peers. “Many ninja [are said to have had] their origins in the lower social classes,” Turnbull wrote, in an earlier book. “Their secretive and underhand methods were the exact opposite of the ideals of noble samurai.” Accounts describe them hiding in wait for days, infiltrating enemy territory, or serving as spies or assassins.

If they ate like other farmers, says researcher Makato Hisamatsu, from Mie University’s recently opened ninja research center, they might have had two meals a day, mostly made up of millet, rice bran, miso, and wild vegetables and plants. “They’re thought to have eaten grasshoppers, snakes, and frogs, too,” he told the Japanese magazine Aera. “It was a more balanced diet than today.” Certainly, the nutritional advantages of brown rice are well documented—though insects, reptiles, and amphibians seldom appear in today’s many ninja-inspired healthy eating manuals.

But source texts dating from the late 17th and 18th centuries suggest several distinctions between their diet and that of their farmer peers. Ninjas are said to have avoided particularly pungent foods, for fear of being sniffed out by the enemy, Hisamatsu told the Japanese Health Press. Garlic, leeks, and other members of the allium family were all off the menu. (Red meat was too, though most people living in medieval Japan were Buddhist or Shinto, and therefore mostly vegetarian.) There’s a scientific basis for this concern: Recent research shows marked changes in body odor for men who adopt a vegetarian diet, while at least one study linked increased garlic consumption with a more pleasant, but perhaps more pungent, personal musk.

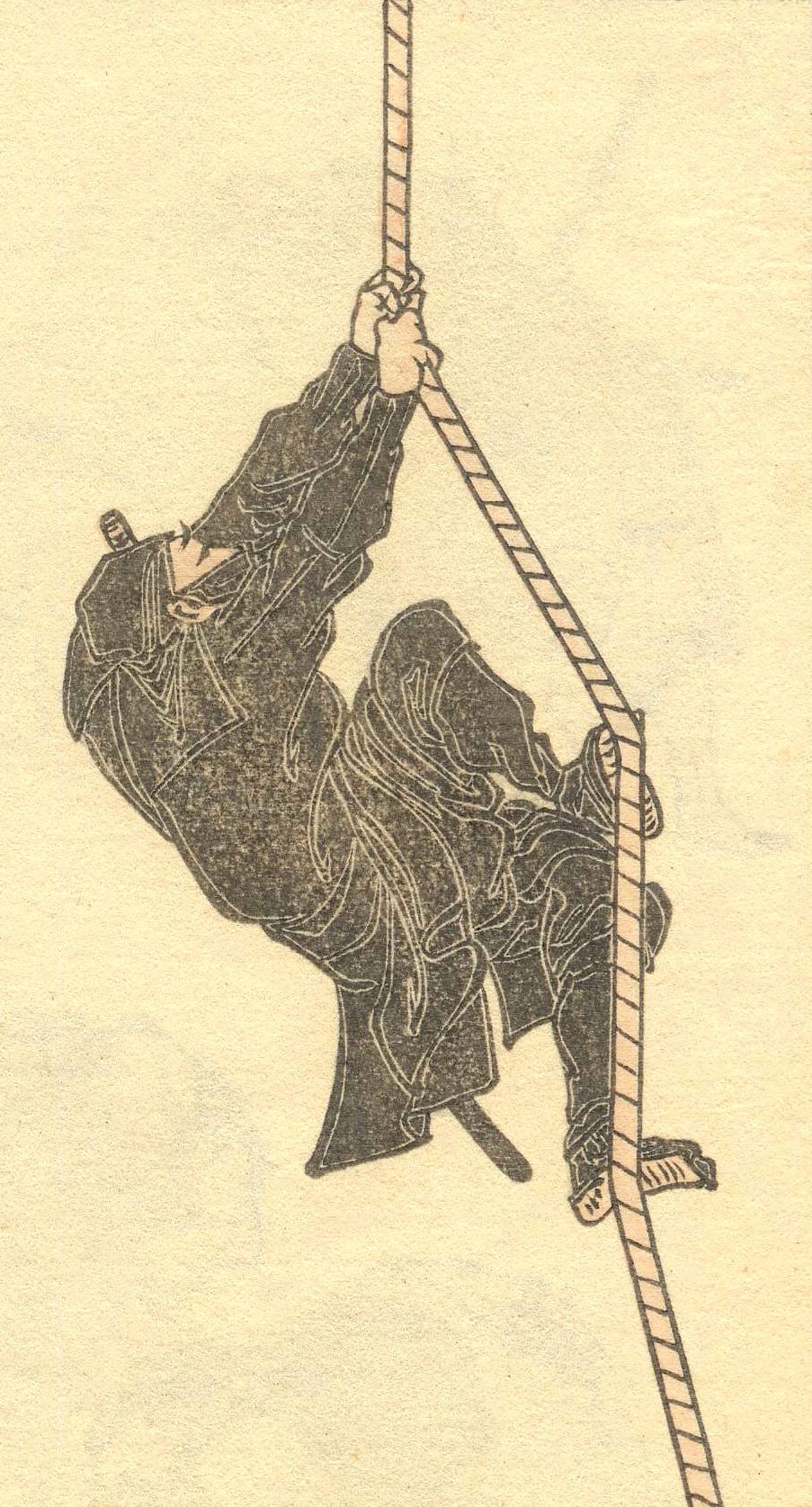

There were other differences. Ninjas are said to have kept an eye on their waistline to remain agile, Hisamatsu said. He described a commonly cited “iron-clad rule,” which stipulated that they should not weigh more than 60kg, or about 130lb: the then-standard weight of a bag of rice. In practice, this meant observing a simple, nutritious regime, so that when they needed to “be a stealthy ninja” (and hang from ceilings or scale walls), they’d be light enough to do so with ease.

The famous Bansenshukai is one of the best-known source texts about ninjas, though it dates to 1676, long after their supposed heyday. It’s a hodgepodge of documents, many of which draw extensively from Chinese military philosophy, and reads almost like a manual—a how-to guide that claims to be the ultimate accumulation of Ninjutsu knowledge, and in the process, helped lay the foundation for the ninja mystique. It includes instructions for how to make so-called “hunger pills” that can fuel long, secretive journeys when food might be scarce.

One recipe combines Japanese yams, cinnamon, glutinous rice, and lotus pips. Another instructed ninjas “on the go” who lacked adequate rations to make a powder out of pine bark, ginseng, and white rice, and then steam balls of the mixture in a basket. “Divide this between 15 people and they will not starve, even if they eat nothing else for up to three days.” Modern calculations suggest that each ball had about 300 calories—not enough for a meal, perhaps, but a decent, nutrient-dense snack for the long road ahead.

The Ninja Museum of Iga-ryu, a Japanese museum dedicated to ninjas and their history, describes a similar “thirst ball,” which helped ninjas avoid dehydration. They were made with crushed umeboshi pulp, rye ergot fungus, and crystallized sugar—a potent, electrolyte-rich combination of foods often used today as hangover cures. Such pills would have been crucial for these “long-distance scouts,” writes Antony Cummins in Samurai and Ninja: The Real Story Behind the Japanese Warrior Myth. “They were expected to be in the field for extended periods of time with little or no food, and their health was expected to decline.”

Texts by the 18th-century Japanese military writer Chikamatsu Shigenori describes another use for food in ninja culture—as a way to send secret messages. To communicate a date, ninjas could send pieces of fish, with the size and number of pieces corresponding to the month and day. “To promise to [carry out] treachery, you should send salted fish,” writes Shigenori. “When you are going to commit arson, you should send dried fish.” Sweet cakes meant a call for reinforcements; bread rolls were a call for forces to attack the enemy from the rear. Rice cakes indicated a request for provisions—though presumably ninjas wouldn’t send them unless they were quite sure they’d be resupplied. The fighters apparently sent an anodyne letter along too, to protect the messenger if their bounty fell into the wrong hands.

All of this, however, should be taken with at least a sprinkle of salt. There’s a textual basis for these dietary innovations, and many have a scientific basis to boot. But experts still question to what extent “ninjas” even existed and debate how much of our knowledge is centuries-old fabrication, founded on layer upon layer of legend. There’s only one contemporary source that describes ninjas—not much to base an entire military tradition on. While Turnbull accepts that some written records may have been destroyed, “the important point is that there are no authentic records after it.” Those we have are shaky, and date from long after the time ninjas allegedly roamed Japan.

Whether or not ninjas truly ate the way the texts describe is hard to say. But what these sources do reveal is the origins of a dearly-held national tradition, and where our modern conception of these fighters may come from. As early as the 1670s, people imagined ninjas as being like a deadly gas: lighter than air, capable of infiltrating impenetrable areas, and undetectable, even by smell.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook