What the Color ‘Haint Blue’ Means to the Descendants of Enslaved Africans

In the Lowcountry, the unique shade is both protective talisman and source of unspeakable suffering.

Beaufort County, South Carolina, a marshy world of low-lying coastal islands, is awash in blue. The cerulean of the skies that darken to shades of cobalt in storm-kissed summers. The blue-gray of the churning Atlantic. The sapphire waters of the rivers and saline estuaries that account for almost 40 percent of the county’s 923 square miles.

But while the color blue dominates Lowcountry skies and waters, for centuries it was nearly impossible for human hands to reproduce. Only indigo—a leggy green plant that emerges from the soil in bushy, tangled clumps—can generate the elusive jewel tones.

In Beaufort County and elsewhere in the Lowcountry of South Carolina and Georgia, blue had the power to protect enslaved Africans and their descendants, known as the Gullah Geechee, from evil spirits. But the color was also the source of incomparable suffering. Indigo helped spur the 18th-century transatlantic trade, resulting in the enslavement of thousands.

The town of Beaufort, the county seat of the eponymous Lowcountry district, is accented in blue. The elegant riverside town was one of the South’s wealthiest before the Civil War, and one of the few left standing by the Union Army, which set up a base of operations here after its residents skipped town in the Great Skedaddle of 1861.

Dozens of antebellum mansions still line the streets, restored to the opulence of their plantation days. The ceilings of their broad summer porches are painted almost universally in just one color: a soft, robin’s egg blue.

This “haint blue,” first derived from the dye produced on Lowcountry indigo plantations, was originally used by enslaved Africans, and later by the Gullah Geechee, to combat “haints” and “boo hags”—evil spirits who escaped their human forms at night to paralyze, injure, ride (the way a person might ride a horse), or even kill innocent victims. The color was said to trick haints into believing that they’ve stumbled into water (which they cannot cross) or sky (which will lead them farther from the victims they seek). Blue glass bottles were also hung in trees to trap the malevolent marauders.

While “haint blue” has taken on a life of its own outside the Gullah Geechee tradition—it’s currently sold by major paint companies such as Sherwin-Williams, and marketed to well-to-do Southerners as a pretty color for a proper porch ceiling—the significance of the color to the descendants of the Lowcountry’s enslaved people remains.

In Rantowles, a hamlet 14 miles south of Charleston, Gullah families like Alphonso Brown’s painted their homes in haint blue not just because it is customary, but because they fear the havoc that evil spirits might wreak if they abandoned the tradition.

Yet not all Gullah Geechee identify with the color’s use. Oral histories recorded as late as the 1930s and 40s mention haint blue, but a lot was lost when the community became less isolated and more spread out during the mid-20th century.

“Haint blue was never mentioned in my family on Hilton Head Island,” says Louise Miller Cohen, founder of the island’s Gullah Museum. “People are saying that we paint our houses blue to ward off the evil spirits. If that was true, all the houses on the island would be painted blue.” Nevertheless, the museum—once the home where her father lived—is painted blue.

“Indigo dye is deeply rooted in African culture,” says Heather Hodges, executive director of the Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor National Heritage Area. So “is the symbolic use of the color blue to ward off ‘evil spirits.”

In her book Red, White, and Black Make Blue, Andrea Feeser describes West African spiritual traditions that included wearing blue beads or clothing for protection. “Fetishes,” powerful amulets made out of everyday objects, also often contained blue materials.

In some cultures, indigo itself has spiritual significance. In Blue Alchemy, director and producer Mary Lance’s film about indigo around the world, women at a Nigerian workshop are documented delivering a prayer to the Yoruba indigo deity Iyamapo.

Haints and boo hags, too, stem from African spiritual traditions—a spirituality in which conjure and color symbolism are essential, according to Rituals of Resistance, Jason R. Young’s book on African-Atlantic religion. Root workers, practitioners of these rituals who often go by the title Dr. Buzzard, were among those forced across the ocean in bondage.

Almost 300 years after their arrival, there aren’t many Dr. Buzzards left in South Carolina and Georgia. (There are a few, however, including a root worker in Atlanta whose grandparents chose him to train in their spiritual traditions. “I went to live with them when I was a year-and-a-half [old],” he says. “I was 16 when I quit school to do voodoo full time.”)

Yet within recent memory, Lowcountry root workers weren’t so hard to find. In the 1940s, Dr. Buzzard (aka Stepney Robinson) was a fixture at the Beaufort County Courthouse, where he sat at trials “chewing the root” to sway a judge’s ruling. In the 1980s, another Dr. Buzzard (aka Ernest Bratton) shot to fame with his video “Voo Doo, Hoo Doo, You Do,” appearing on Late Night with David Letterman and The Oprah Winfrey Show.

Root workers may have mostly moved on from Beaufort County, but HooDoo beliefs still remain. So does the significance of indigo and the color blue in shaping the Gullah Geechee community. Among their ancestors were more then 70,000 men, women, and children brought from West and Central Africa to provide the labor required for the South’s roughly 40-year foray into the plant’s growth and production of indigo dye, according to Young’s book.

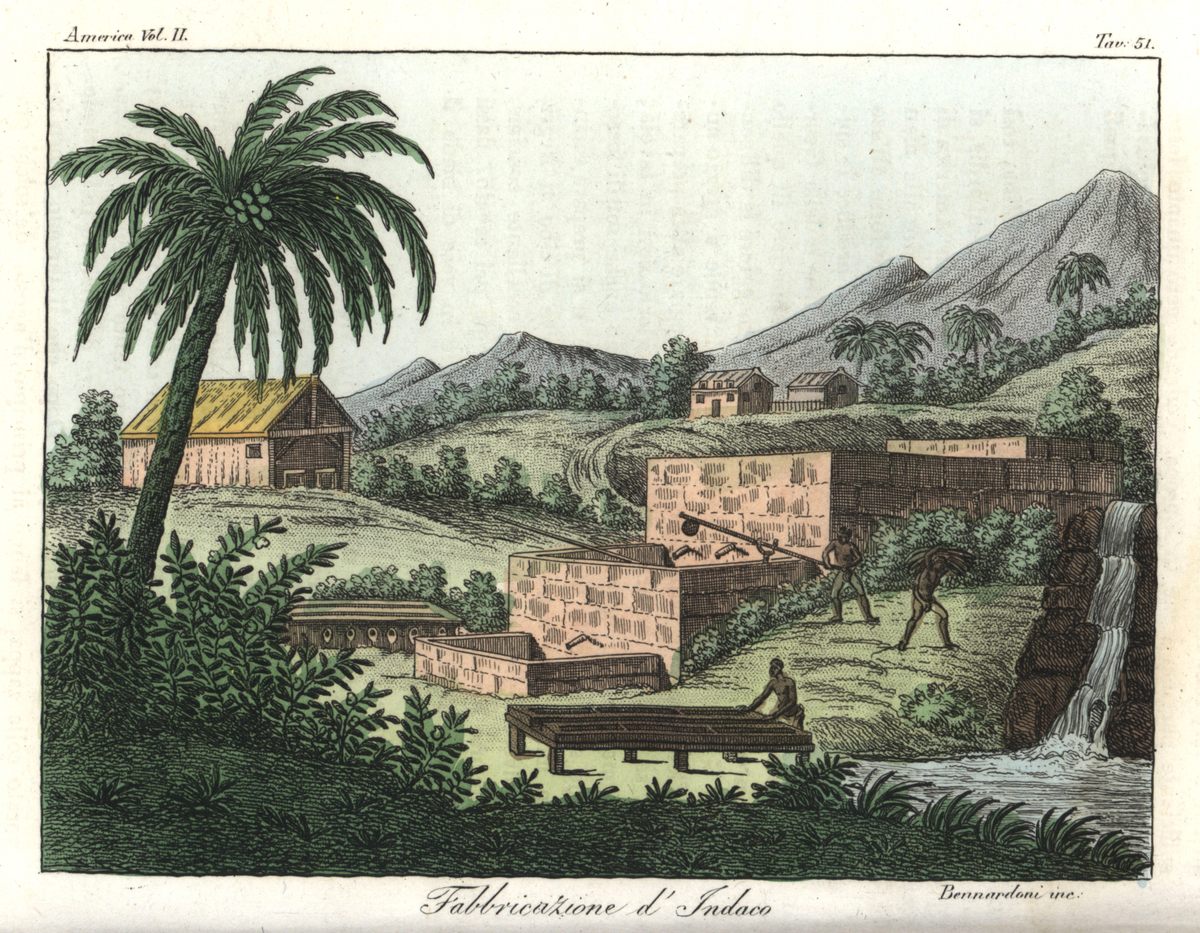

Indigo was first planted in South Carolina in 1739. Less than 30 years later, the colony was annually exporting a million pounds of indigo dyestuffs. Today they would be worth more than $30 million a year. At least some of the knowledge for processing indigo dye came from the enslaved themselves: Indigo traditions in West and Central Africa are at least five centuries old.

At the Nigerian workshop Lance features in her documentary, the plant is pounded with sticks that remove and crush the leaves, which are then formed into balls. The balls are sprinkled with wood ash, then left to dry for seven days before being combined with water in dye pits. In Kano, Nigeria, pits dating back to 1498 are still in use today.

South Carolina’s indigo production came to an abrupt halt at the end of the Revolutionary War. “The people in South Carolina were producing indigo exclusively for the British market,” says Lance. “So when [the United States] was no longer a British colony, they no longer had that market anymore.”

By the mid-19th century, when synthetic blue dye became available, indigo almost disappeared from Beaufort County and the rest of the Lowcountry. Almost. Now a Gullah Geechee movement to reclaim indigo and the blue dye it produces is afoot.

As a child, Cohen played among the remnant indigo planted by her enslaved ancestors. In 2016, she planted her first seeds at the museum.

“The species that we grow have a peach-color flower,” she explains. Her hope is to grow enough of the plants to be able to process and produce dye to use in local workshops, strengthening her community’s connection to their ancestral past. “I’m interested in learning all I can about the crops that caused my people [the] loss of their freedom,” she says.

Cohen’s sentiment has blossomed elsewhere in the Lowcountry, too. Though there aren’t many artisans around who know how to dye with indigo, Hodges says that the color “is widely used by Gullah Geechee visual artists and filmmakers as a way of expressing their shared Gullah Geechee heritage and history with indigo cultivation.” The film Daughters of the Dust; the novel Sassafrass, Cypress & Indigo [sic] by Ntozake Shange; and the artwork of Diane Britton Dunham all feature indigo or the color blue.

Hodges’s organization recently engaged in a year of events to introduce community members to the craft. The reintroduction of natural indigo dyes, she says, has sparked a lot of enthusiasm.

“Many of the West African techniques involve wax, starch, and stitch-resist techniques, sometimes using stamps,” says Hodges. “That can be difficult to teach. [But] we just did a popular workshop that encouraged people to dye African head wraps and scarves as a way of incorporating African cultural expressions.”

But as indigo undergoes a resurgence in the Lowcountry, along with other traditions including the Gullah language and foodways, the community hasn’t forgotten the inhumane conditions that led to their arrival and early life in the South.

“If [reparations were]* attached to indigo,” says Cohen, meaning if indigo were part of the discussion regarding what the Gullah Geechee are owed for the horrors their ancestors endured, “they would do everything possible to keep the word from ever being mentioned.”

* Correction: This quote was updated to correct a misstatement. “Repatriation” was changed to “reparations.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook