For Centuries, English Bakers’ Biggest Customers Were Horses

A crusty, dense bread got the country’s hardworking equines through long days.

In medieval England, people consumed two to three pounds of bread every day. But their appetite for bread was likely nothing compared to that of medieval horses who, after a day spent lugging cargo at high speeds across the British Isles, would often devour coarse loaves of horse bread.

Today, feeding bread to a horse might seem like the whimsy of a sentimental pet owner. But in pre-industrial England, it was the best technology available for powering the horses on which English society relied.

Horse bread, typically a flat, brown bread baked alongside human bread, fueled England’s equine transport system from the Middle Ages up until the early 1800s. It was so logistically important that it was more highly regulated than its human counterpart, with commercial bakers adhering to laws dictating who could bake horse bread, as well as the bread’s price, size, and occasionally even its composition. The ubiquitous bread was made from a dough of bran, bean flour, or a combination of the two, and typically was flat, coarse, and brown.

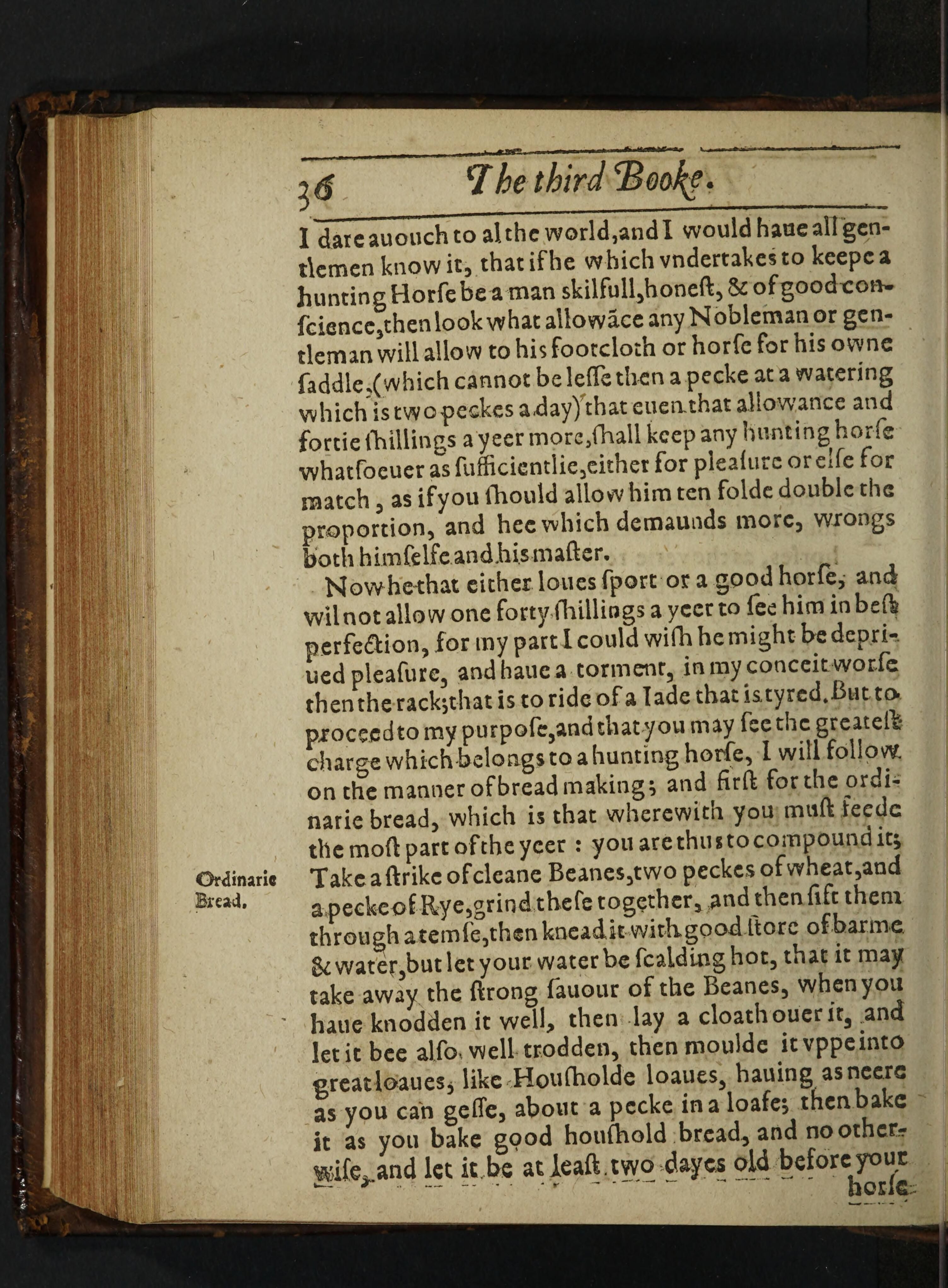

“In England and other places … a certain bread which they call horsebread … is so general among them, that you shall not find an inn, ale-house or common Harbor, which doth want the same,” writes Gervase Markham, a horse trainer and cookbook author, in a 1616 treatise on rural living called Maison Rustique.

According to some estimates, medieval horses consumed about 20 pounds of food per day. These huge animals were responsible for hauling people and cargo across England at high speeds. After a long haul, exhausted horses had to rebound quickly for another trip, so they needed carbohydrates and protein, fast.

Bread solved this problem in two ways. First, it saved time and energy because it was “pre-digested,” says William Rubel, author of English Horse-bread, 1590-1800 and a leading historian—and baker—of this functional bread. “Bread, where you’ve ground the food and baked it, pre-digests it, so you get more calories released more quickly.”

Second, horse bread concentrated, in a travel-friendly object, nutrients that owners would otherwise have to gather from vast quantities of grain and grass. “I am convinced that horse bread is a very reasonable solution for the ongoing problem of how do you feed your horses. They require a massive amount of feed and in a medieval economy, it must have been a logistical nightmare, especially while traveling,” writes Madonna Contessa Ilaria Veltri degli Ansari, a medieval reenactor who baked horse bread for her own modern-day horse based on ancient English recipes, in a paper on the topic. “I consider that horse bread is the period analogue for the pellets we use today.”

Rubel agrees: “Companies for elite horses, you’re going to find that they pelletized those breads.”

Horse bread also allowed professional bakers to turn their leftovers into a commodity. At the time, commercial bakeries produced most of the bread that English people consumed. The most sought after form of bread was white bread, which required that a baker sift the whole-grain, stone-ground wheat they received from the miller, removing the grain’s hard outer layer, called “bran,” from the white flour. After turning the white flour into expensive white bread, bakers could recycle their leftover bran to make horse bread by adding only a bit of flour and water, barely kneading or leavening the dough, then baking it.

Horse bread made this way emerged as “big, flat hockey pucks” that weighed around five pounds, Rubel imagines. Bakers also made horse breads out of cheap bean flour or a mixture of bean flour and bran.

This brown bread was probably more appetizing than it sounds, Rubel says. Bran carries the nutty, complex flavor associated with whole grains, and to form bran into a dough, bakers often turned to rye flour, a cheap option that is significantly sweeter than wheat.

But in pre-industrial England, horse bread carried the taste of shame. The dark bran bread sat at the bottom of a hierarchy that gave brown bread to farmers and servants and reserved white bread for the elite. Indeed, Englishpeople turned to horse bread during times of strife, and the abject poor likely ate it year round. And since horse bread was fed to laboring animals, humans who ate it were looked upon with disdain. In Ben Johnson’s 1598 comic play, Every Man Out Of His Humour, a wealthy character insults a group of peasants with the phrase, “You thread-bare, horse-bread-eating rascals.”

By the 1500s and 1600s, elites pushed this distinction further, feeding an enriched, white horse bread to race horses nearing race day. Gervase Markham, who wrote many of the detailed horsebread recipes that have survived to this day, spearheaded this change. Influenced by the rising empirical science movement, Markham bucked a tradition of giving horses herbs that imparted magical qualities, instead advocating that horses be fed richer, more refined breads as they neared race day in order to increase their nutrient intake.

In his recipe for “Last Bread,” fed to horses during their last fortnight of training, he writes that after mixing wheat and bean flour, bakers should “then knead it up with very sweet Ale Barm, and new strong Ale, and the Barm beaten together, and also the Whites of at least twenty Eggs, in any wise no water at all, but instead thereof some small quantity of new milk.” Left to rise before baking, this “Last Bread” was fluffy, white, and rich, similar to the white table bread the upper class enjoyed for dinner.

During the industrial era, bread fell out of the diet of the English horse. In 1830, the Liverpool and Manchester Railway opened, becoming the first steam-powered railway to carry both people and cargo between English cities. Within a few decades, trains replaced horses as vehicles for heavy lifting, so horses no longer needed nutrient-dense horse bread.

Today, scholars such as Rubel look to horse bread recipes as windows into lost English baking traditions, particularly those of the English poor. “The best descriptions in the early modern period of how to make bread are the descriptions that Gervase Markham wrote for race horses. That’s because money was on the line,” he says.

As part of his research, Rubel bakes multiple horse bread varieties and offers them to people to sample. For contemporary Westerners who prize whole grain over processed flour, the horse bread of bran and rye, once debased as a bread of poverty, is usually the crowd favorite for its sweet, nuanced taste. “It’s fabulous,” he says. “It’s absolutely fabulous.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook