Krampus Is the Christmas Icon We Need—And Maybe the One We Deserve

At Milwaukee’s Krampusnacht, we go in search of the essence of Santa’s unholy enforcer.

It’s the first time I’m wearing the dog muzzle in public. I’d been fussing with it for days in the privacy of my dining room, along with other found items: gardening knee pads, black electrical tape, cowbells snatched up on clearance (because you can never have too much cowbell).

Now, I’m wearing all that, along with an old weightlifting belt and yards of fake fur, stitched and glued into something that resembles the offspring of a Wookiee and a Highland cow. I’ve joined a mob of about a hundred characters parading down the street. The local Spielmannszug Milwaukee, a traditional German drum and bugle corps in felt and wool Alpine hats, leads the way in orderly columns. Behind them flows chaos: a coven or two of glam witches, angels in various degrees of falling, an antlered wendigo, a few Mari Lywd (the traditional Welsh singing horse skull-on-a-stick), and a pair of Santa hat-wearing hodags, the beloved cryptid of Wisconsin’s Northwoods.

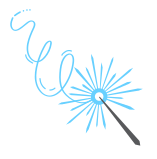

As onlookers lining the sidewalks shout and cheer—and a few children cower in terror—my group brings up the rear. Following St. Nick in his resplendent velvet vestments and crimson-and-gold mitre, we are a bestial lot. Some lumber, walking sticks thudding on the pavement, while others lope or dart around the edges of the procession to swat at the crowd pressing forward for a better view. Our chains clank and jangle, and, with every step we take, the chilly air reverberates with bells, bells, bells announcing the approach of Santa’s sinister sidekick, the Krampus.

It’s the Fifth Annual Milwaukee Krampusnacht, an event that has taken over the city’s historic Brewery District. Milwaukee is a city with deep German roots, and this neighborhood, centered around the atmospheric 19th-century Pabst Brewery, with narrow streets and castellated facades, is particularly evocative of the Old World. It’s a fitting backdrop for the horde of Krampusse emerging from the shadows to mete out punishment to the naughty. Evolved from Central Europe’s pagan past and reimagined by Church elites as a kind of unholy enforcer, Krampus is now a global icon for the digital age. But what explains the ascent from obscure Alpine tradition to a 21st-century celebrity that has inspired Krampusnachten around the world? What brings people out of their warm homes, on a night when temps flirt with freezing, to stand on a sidewalk and hope to get thrashed by a masked demon? And what do the people behind the masks get out of transforming into the cool ghoul of Yule? To understand the Krampus, I must become the Krampus.

Weeks earlier, just before Halloween, I got a crash course in all things Krampus. In the Pabst Brewery’s cozy cafe, lined with stained glass windows and gleaming, detailed woodwork that would have been at home in a posh Munich Kaffeehaus, I met with Krampusnacht cofounder and event director Tea Krulos and Izzy Jaecks, president of the Milwaukee Krampus Eigenheit.

Each year, the group’s members make up the bulk of performers in the Krampuslauf, or parade, though Krampusse come from all around the country to join in. Eigenheit translates as a quirk or peculiarity, and it captures the spirit of wild creativity on display each year during Milwaukee Krampusnacht. While some Krampus troupes wear identical costumes and masks, particularly in Austria, the Milwaukee event is more about individual expression: Fur features heavily in most traditional costumes, but one Milwaukee Krampus wears a cowl of gleaming black feathers—“They photograph better,” she tells me—while another is kitted out in Ren-faire-style tights and brocade. Some wear two-foot-long wooden masks similar to those worn in Bavaria and Tyrol, where the tradition began, but many more sport horned silicone masks straight out of a Hollywood special effects workshop.

When it comes to Krampus, there’s only one thing that’s non-negotiable.

“My costume is 40 pounds, and about 10 pounds of that is bells,” Jaecks says. “To be Krampus requires bells and chains. Bells signal his arrival, and chains symbolically bind him to the Catholic Church. He is, after all, St. Nicolas’s hellish minion.”

In the 16th century, the Church in Central Europe co-opted existing local and regional traditions regarding some kind of evil creature—descriptions vary—and made it into a devil who tested the faith of good Catholics. This was a tumultuous time, when the Counter-Reformation emerged in response to the expansion of Protestantism, particularly in Bavaria and Tyrol.

“The Jesuits start popularizing plays that involved St. Nicholas but also the devil. It’s the first time in European iconography that the devil is impersonated in theatrical performances,” says Matthäus Rest, a social anthropologist at the Max Planck Institute of Geoanthropology in Jena, Germany. Rest has studied the Krampus phenomenon worldwide, particularly in its Alpine birthplace. In some regions, there are accounts of St. Nicholas and the demon figure going door to door, entertaining but also testing occupants on their catechism—possibly in an attempt to root out Protestants.

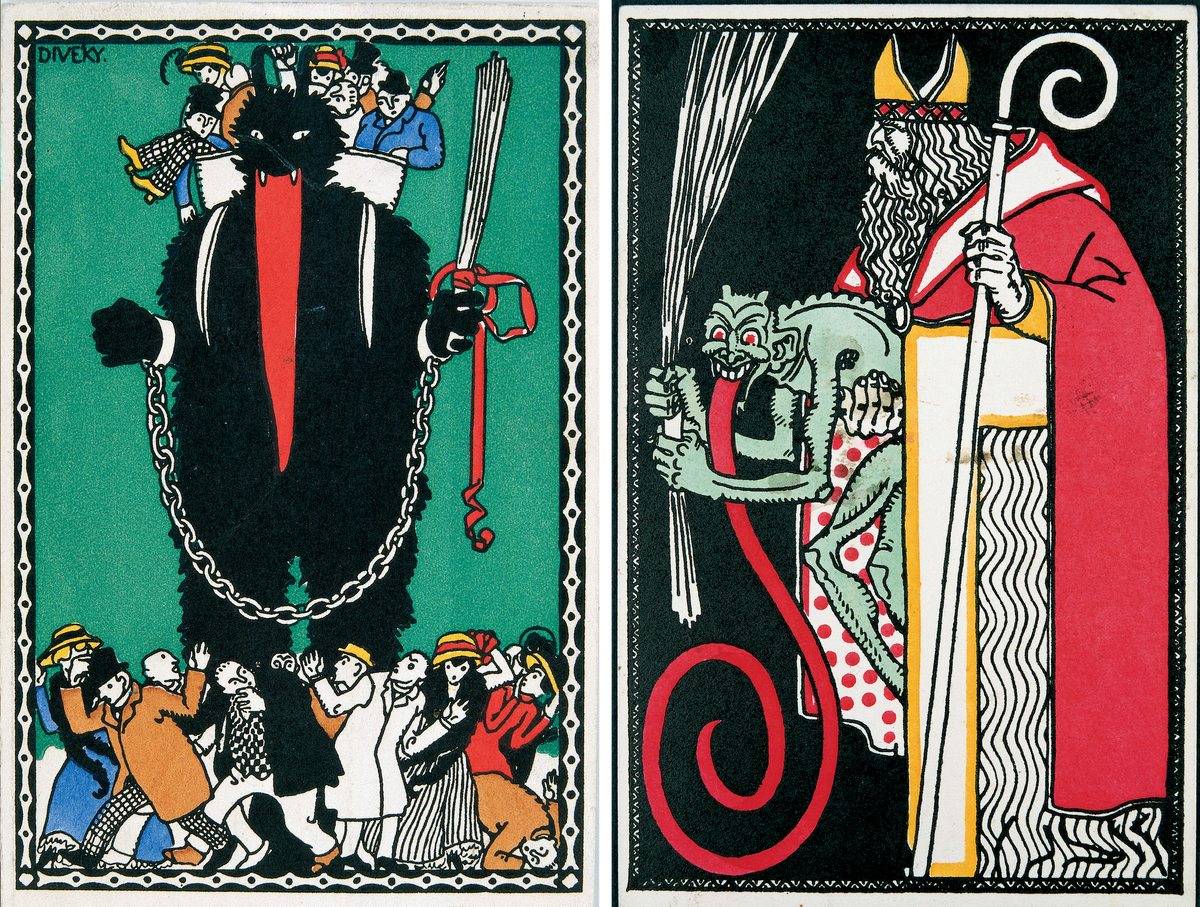

For a few centuries, this devilish figure remained known only in these Alpine areas. The modern Krampus first reared its horned head in 19th-century postcards exchanged mostly in Austria. The goat-demon creature often menaced children, swatting them with switches or carrying them off in a basket or sack. In some of the images, however, the furry fiend stands beside or just behind St. Nicholas, a good cop–bad cop act judging the children at their feet.

During this period, on the heels of the Industrial Revolution and just at the start of mass urbanization, when many people were uprooted from rural areas, “There was institutionalization of relatively local customs. A lot of traditions were formalized, but also a lot of them were invented,” says Rest.

In fact, the very name Krampus, derived from the German verb “to claw,” appears to have been one of those invented traditions during this era. “The word Krampus comes in very late,” says Rest. “Even to this day, many old people in the regions we did fieldwork in don’t refer to the figure as Krampus. They use localized terms.”

The Alps are, in fact, full of similar characters, from Switzerland’s Schmutzli (known as Père Fouettard in French-speaking regions of the country) to Austria’s Perchten, minions of the winter witch Frau Perchta. Nearly every mountain valley village had its own version of the furry, horned punisher of the wicked, laden with bells to warn of its approach.

Throughout the 20th century, some of these villages had homegrown troupes of costumed villains who went house to house or paraded through the streets, traditionally on December 5, the day before St. Nicholas Day. (Milwaukee holds its Krampusnacht on the weekend closest to that date because hey, even Krampus has to punch the clock.) Many of these local Alpine traditions involved significant physical contact between the beasts and locals, from good-natured swats with broom-like switches to serious shoving. But they remained a quirky regional activity—until the internet came along.

As social media spread around the world, so did Krampus. Vintage postcards were plucked from archives, scanned, and sent as alt-holiday greetings. Travel blogs about witnessing obscure Alpine traditions racked up the likes and inspired homegrown events. Within the last decade, the character has featured in books, comics, and a campy Hollywood movie starring a creature more Freddie Krueger than Krampus.

Krampusnacht director Krulos, who also runs an annual paranormal conference in town, remembers his first face-to-devil-face experience with the Krampus pop culture phenomenon. A small group of Minnesota Krampusse visited the 2016 ParaCon and mesmerized the crowd. “It was like they were the damn Beatles,” Krulos says.

With a few friends, Krulos put together a modest Milwaukee Krampusnacht the following year. “We thought, it’ll be cool if 100 people show up,” says cofounder Rob Schoenecker. “The lines were out the door.”

Milwaukee Krampusnacht has grown each year since, expanding to the Brewery District for the first time this year. During a season when weekends are stuffed with parties, shopping, school pageants, and other demands on time—and when it’s dark well before 5 p.m., with temps regularly below freezing—the appeal of spending hours outside waiting for the chance to be menaced by an anti-Santa isn’t obvious. But now may be when we need Krampus most.

Beat him! BEAT HIM!” a woman screams at me, grabbing her tween son by the shoulders, spinning him around and shoving him in my direction. I oblige, swatting the back of his jeans a few times with my switches. The boy rolls his eyes, but there’s a little smile flitting around his mouth. His mom hoots with delight and films it all with her iPhone. I continue walking, a little ungainly because my cloven hooves, made of foam and electrical tape, are starting to come apart. A few feet ahead of me, a middle-aged man has jumped off the sidewalk and into the street, hands on knees and looking over his shoulder at me as he presents his rump and shouts, “Me next! I’ve been SO naughty!”

Maybe it’s a primal alarm response to the multitude of bells, or the sharpness of the cold December air, but spectators seem more riled up at Krampusnacht than for, say, your average Halloween parade. Event director Krulos says he’s spoken with many attendees who return year after year, including some who tell him it’s become their favorite holiday tradition.

“I love the love that people have for this event,” he says. “It’s a really fun thing between Thanksgiving and Christmas, which is not a fun time for a lot of people. There’s a lot of stress.”

The Krampusnacht tradition might provide an outlet for December’s particular pressures, such as overscheduling, overspending, and amped-up family tensions. But Rest also thinks Krampus is appealing for another reason: Through Krampus, we can experience the vicarious, instant satisfaction of doling out punishment to those deserving of it.

“The Krampus, by breaking the rules, is the most ethical being in the community,” Rest says. “He is there to smack things, throw things around, and hit people, but at the same time he is full of ethical substance, and through the Krampus the children are taught what is good and what is bad.”

Standing up to Krampus can also be a test of bravery, particularly in Alpine villages where more rough-and-tumble Krampuslaufs can leave spectators bruised. At least here in the United States, standing on the sidelines during the parade is akin to visiting a haunted house for Halloween: The scary sights and sounds may rev us up physiologically, but we’re in no real danger. It’s fear for fun. It’s no coincidence that some members of the Milwaukee Krampus Eigenheit also work as actors in seasonal haunted houses. They love the thrill of pushing people to the edge of terror in the name of entertainment. But ask the group as a whole why they do it and you’ll get answers as varied as their costumes.

After a chilly outdoor photo shoot ahead of this year’s event, local Krampusse fill one of the small pubs in the Pabst Brewery complex in various states of undress—some in parkas and jeans, others still layered in fur.

While Krampus performers in past centuries were traditionally young white men, 21st-century Krampusse are much more diverse. Even in the traditionalist bastion of Austria, Rest says, women, members of the Turkish diaspora, and other communities frequently participate, sometimes forming their own troupes. The Eigenheit group gathered to warm up over a beer reflected this more inclusive vision.

“It’s a celebration of creativity,” says Kacey Tait, who joined the Eigenheit after moving to Milwaukee a few years ago and searching for a sense of community. Instead of being Krampus, she appears at the event as the lead Dark Angel, an elegant winged creature dressed in vintage-shop finery and wearing unnerving black contacts. Like several Eigenheit members, she has no ancestral roots in the European Alps—Tait’s heritage is Scottish and Polish, and others mention Mexican or Greek ancestry—but she says she also appreciates the sense of history and tradition.

Schoenecker, who recently retired from the Milwaukee Fire Department, also does World War II reenactments. He enjoys the chance to become different characters. This year he’s St. Nick, but he’s been Krampus before as well. His wife, Michelle Schoenecker, has long played another, more practical role: a Krampus handler who helps the horned, masked, nearly-blind performers find their footing, literally. When her husband and friends first donned their Krampus costumes, she says, “They didn’t realize you can get gored. It’s an occupational hazard. Visibility is really low.”

“The time between Thanksgiving and Christmas is not really a happy time, but now I can celebrate it the way I want to. I can dress up as a stinky goat man,” says Eigenheit president Jaecks, now a machine operator who says working in retail for 17 years taught them to hate Christmas. While they threw together their first Krampus costume in a bar—perhaps the most Milwaukee thing ever—their current gear is an expensive collection of real fur and animal horns with a mask made mostly of leather, mounted on a bicycle helmet.

“I don’t even know how much it cost because I’ve built it over the years,” Jaecks says. “But it’s me. It’s mine. It’s freedom, it’s power.” They don’t wear the costume so much as transform into Krampus, Jaecks adds. “It’s about becoming something else.”

Their words echo a phenomenon Rest encountered when conducting field interviews in Austria: “Through our interviews, active Krampus often said, ‘I’m not playing, I’m becoming something else.’”

Moments before the parade, the Krampusse crowd into a narrow alley beside a loading dock as the Spielmannszug corps begins to play half a block ahead of us. The percussive drum beats bounce off the surrounding brick walls and the bugles reverberate in the hard plastic of my muzzle (technically, it’s my dog’s). In response to the music and the electric feeling of anticipation, the Krampusse spontaneously howl and roar and jump up and down. Soon the cacophony of bells drowns out the band.

Instead of a Hollywood horror look, Jaecks’s costume is more folk art–inspired, and resembles a black goat on its hind legs. They stand beside another Krampus who, aside from the horns, might be mistaken for a troll from The Lord of the Rings. A third Krampus walks past, trailing a scrap of filthy velvet behind his tattered Father Christmas robe, carrying a sack of Devil-knows-what over his shoulder. They are all different, and they are all Krampus—though they likely would be unrecognizable to the first humans to tell tales of a malevolent beast on the prowl during the long dark of winter.

As with most traditions with deep roots in the past, exactly where and when the figure who would become Krampus originated—and what the earliest version looked like—have been lost. But even far beyond the European Alps, almost every culture at a latitude high enough to experience winter has its own seasonal menace. The Anishnaabe of the Great Lakes warned of the wendigo, an insatiable, antlered flesh-eater who came with the ice. In Iceland, the giant cat Jólakötturinn hunts naughty children during the darkest time of the year. From Japan to Bulgaria, there’s a whole awful menagerie of furry, often horned or antlered creatures—many wearing bells to announce their arrival—who show up in the cold months.

“Winter is a time of magic and of storytelling,” says Jaecks, but it is also a time when survival was most challenging for our ancestors. Run out of firewood or other fuel, or grain or dried meat, and no amount of storytelling would save you. The monsters of winter lore—and even the Krampus, who was known to steal a child or two—are allegories for the brutal truth that, for many, winter was a time of death.

Intriguingly, more than a decade ago, University of Iowa linguist and scholar Roslyn Frank connected Krampus and similar Alpine characters to some of the other furry, bell-wearing beasts that traditionally appeared to villagers in winter to pass judgment or bestow good luck. These traditions, from Basque Country and Sardinia to Poland and the Baltic States, may have their roots in a lost prehistoric ritual around bears, an animal both feared and worshiped in the Paleolithic, Frank suggested.

I embrace Frank’s theory, because my Krampus is decidedly less goat-demon than shaggy bear. Specifically, a teddy bear. A few days before Krampusnacht, I stood over the mask with scissors, ready to lop off the boop-able nose and redo the snout entirely to replace a comic overbite with something more menacing. I messaged Jaecks about my conundrum: “My Krampus is too cute. I’m Kuddles the Krampus.” They replied almost immediately: “It’s fine.”

Over the years, whenever Jaecks transforms into Krampus, they find children drawn to them with a mix of awe and wonder. Laughter and spontaneous hugging are common reactions. While facing the Krampus can be about confronting fear, it can also be about reaching back into a near-forgotten past, when the long dark of winter was a time of myth and magic, storytelling and survival, in a world where humans were not at the top of the food chain.

I remembered something Rest had told me. He’s not just an academic expert on Krampus: He grew up in Gastein, an Austrian village with one of the oldest traditions of demon-beasts running amok on December 5 each year, sometimes with injurious results. (When recalling his childhood Krampus encounters, Rest uses the term “trauma” more than once.) While he chose to study Krampus rather than suit up, several of his childhood friends have been taking part in the annual Krampuslauf for decades. “When they were 16, 17, it was very much about being cool and masculine and wild and loud,” says Rest. As friends matured and became fathers themselves, he adds, “Many of these guys started to change their Krampus persona and become more interested in talking to and playing with children, and maybe working on their own trauma.”

I put the scissors away. My Krampus is no sneering ogre, and or a faceless, menacing hulk. Our lives are a lot easier than those of the people who began the furry winterbeast tradition, but times are still uncertain and challenging. Kuddles the Krampus would remain.

On Krampusnacht, as I move along the parade route, children who recoil from the more demonic Krampusse smile at me. “This one’s so furry!” squeals a girl in a pink parka as I shuffle past. A young woman, carrying a baby so swaddled against the cold that all I see is a pink nose and enormous blue eyes, steps forward. “Can we take a picture?” I nod, hiding my switches behind her as I lean into the shot.

“Maybe we’re in a new era of inventing traditions,” Rest says, contemplating both the rise of Krampus and the diversification of what it even means to be Krampus. “Everybody will tell you a different story, and nobody is lying. Well. Hardly anybody is lying.” And for those who do lie, Krampus is waiting.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook