What’s the Biggest Bird in the World?

From a flightless giant heavier than a polar bear to a super-glider with a 24-foot wingspan, avians ancient and modern compete for the crown.

The first sliver of fossil he exposed gave volunteer James Malcom pause. He called over his supervisor, Albert Sanders, to take a look. Sanders, curator of the Charleston Museum at the time, was leading the group working its way across a field at the Charleston International Airport. It was 1983, and the site was slated to be part of a new runway. The team had been tasked with excavating anything important from the area before it was turned into tarmac.

Malcolm and Sanders knew they were looking at something enormous. Perhaps, they thought, it was a whale—after all, the Chandler Bridge rock formation beneath the South Carolina city was a prehistoric seabed, a reminder that 25 million years ago, the region was open ocean. Fossil remains of ancient rays, skates, and a toothed whale had been found at the site in the past. But this was no fish or marine mammal. It was a bird.

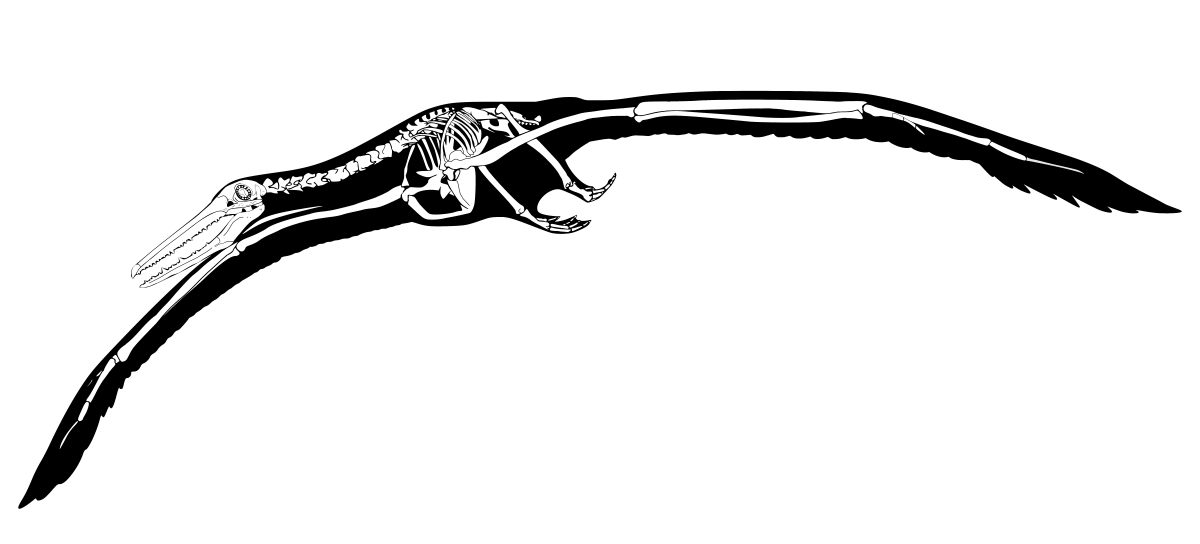

Using a backhoe, the team eventually removed a skull, along with bones from the shoulder, leg, and wing. The fossils sat in the museum for decades, unstudied until paleontologist David Ksepka took a look at what remained of the animal that, in 2014, he would name Pelagornis sandersi. The ancient bird’s wingspan was an astounding 24 feet—without question the largest wingspan of any bird known. But whether P. sandersi was the biggest bird ever depends on how we define the term.

For example, although the Charleston fossil had the widest wingspan, the bird was incredibly light, less than 90 pounds, or “about the same as a large German Shepherd dog,” says Ksepka, now a curator at the Bruce Museum in Greenwich, Connecticut.

Compare that with the bulk of Argentavis magnificens, the enormous, condor-like bird that lived in Argentina’s Andes Mountains approximately six million years ago. Without complete fossils to study, paleontologists have had to estimate the animal’s wingspan using a variety of methods. Earlier estimates stretched as far as about 26 feet, but more recent research has put its wingspan at around 21 feet. However, the bird weighed about 150 pounds, making it the heaviest bird that ever flew.

There were also much heavier birds that never took to the skies. Gerald Mayr, an ornithologist at the Senckenberg Research Institute in Weimar, Germany, says three families dominate discussion of the world’s heaviest-ever birds: the Madagascan Aepyornithidae (elephant birds), the Australian Dromornithidae (thunder birds), and the South American Phorusrhacidae (terror birds). While estimates again vary by method of calculation, it’s likely the all-time heavyweight champ was an elephant bird or a thunder bird, he adds.

Despite their dramatic name, thunder birds were slow, flightless herbivores that roamed Australia until about 50,000 years ago. Of the eight currently known species, Dromornis stirtoni was the largest. “The average size of males was 650 kilograms (1,400 pounds),” says Flinders University paleontologist Trevor Worthy. He notes that “average size is a more useful metric than finding the oddity that was the largest in a species—otherwise you would end up saying that humans were 8 feet tall and weighed 1,000 pounds.”

In fact, thunder birds are locked in a contest with Madagascar’s elephant birds for the heavyweight crown in part because scientists debate whether to consider the average size of the species or that of its largest member. The scale-busting biggest example of an elephant bird—which went extinct just 1,000 years ago—is a specimen of the species Vorombe titan. The flightless behemoth stood nearly 10 feet tall and weighed about 1,600 pounds.

There’s another big question in the battle to be the biggest bird: How does sexual dimorphism play into our calculations? New Zealand’s extinct giant moa, for example, are widely considered to be the tallest birds ever known—but only the females.

“The large female South Island giant moa, Dinornis robustus, was the tallest bird to exist, able to reach over three meters (10 feet) and 250 kilograms (550 pounds) in mass,” says Worthy. By comparison, he adds, even the largest males of the same species were about a third the female’s size. Using a species average, the giant moa would be shorter than either thunder birds or elephant birds.

Meanwhile, Phorusrhacidae might not have bragging rights as the tallest or heaviest birds, but, as the largest-ever meat-eating avians, they are arguably the most terrifying. For most of the past 62 million years—until about 1.8 million years ago—these terror birds ruled much of South America. “Some of them were seven feet tall,” says paleontologist Luis Chiappe, who heads research and collections at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles. With massive beaks and heads as big as that of a horse, he adds, “they must have imparted an extremely powerful bite.”

Today’s biggest birds pale in comparison to all these ancient giants. The wandering albatross, for example, is a relative lightweight at just 16 pounds, with a wingspan of up to 12 feet, half that of P. sandersi. The tallest and heaviest living bird is the ostrich, which can grow to an impressive nine feet but, even at that size, weighs less than 300 pounds. You would need more than five ostriches to equal one V. titan.

While the full evolutionary picture remains incomplete, evidence suggests that V. titan and other ancient bird species got so large because they lived on islands. “In the case of flightless birds, a large size is enabled by the absence of potential predators, mainly carnivorous mammals,” says Mayr. In other words, lions and tigers and bears have a difficult time getting to an island. Since there is no need to hide from large predators, birds and other animals can grow larger, a phenomenon known as island gigantism.

Consider the terror birds, apex predators of South America for almost 60 million years—as long as it was, essentially, a giant island. When the Isthmus of Panama formed at least three million years ago, connecting the Americas, the birds faced new competition. “Once the connection became established, carnivores such as saber-toothed cats, dire wolves, bears, and others migrated south,” says Chiappe. The terror birds were extinct soon afterward.

For the other giant, flightless birds, the predator that spelled their doom was our own species. Archaeologists have unearthed evidence, including cut marks on bird bones and eggshells in ancient trash middens, that coincides with the extinctions of thunder birds, elephant birds, and moa.

The reasons the largest flying birds went extinct—well before humans were around—are less clear, but may be connected to their evolution as specialists, rather than more adaptable generalist species. Ksepka says that P. sandersi’s tremendous wingspan would have made it “a hyper-efficient glider” able to travel long distances without expending much energy. But that also means the big bird probably relied heavily on environmental conditions that can change over time. It’s possible, says Ksepka, that “changes in ocean circulation… disrupted the currents they fed along, or the wind patterns that allowed them to travel between nesting areas and feeding grounds.”

It’s possible that winged giants may one day rule the skies again, if environmental conditions favor their evolution. For now, the closest thing we’ve got is the replica skeleton of P. sandersi that hangs from the ceiling of the natural history exhibit in the Charleston Museum.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook