When the President Was the Quietest Man in the Room

Official portrait of Calvin Coolidge by Charles Sydney Hopkinson. (Photo: Public domain/Wikimedia Commons)

Barring an unforeseen event, like speaking, Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas will reach a dubious milestone: the 10-year anniversary of serving on the Court without having asked a single question. No Justice has ever done anything like this before: in 2012, Justices Alito and Kennedy tied for the second-to-least questions asked per case, with 11.

Thomas had zero. The average of 10 years of zero is zero.

But there have been other high-ranking lawmakers who had a similar distaste for speech. Perhaps the most famous quiet government official is also one of the most fascinating. Near-silent, famously prudish, yet also quite funny and the proud owner of the White House pet raccoon, our 30th president, Calvin Coolidge, makes a pretty strong argument for never ignoring the quiet ones.

Coolidge was born on a farm in tiny Plymouth Notch, Vermont, on July 4th, 1872. His entire young adult life was spent in New England, including college, his early career as a lawyer, and then governor, all in or of Massachusetts; at the time he was sworn into office as the president in 1923, he’d never left the country. His ascendency was far from inevitable, as the surprise nominee as Warren Harding’s vice president who took over after Harding’s death.

Coolidge served as president, finishing what would have been Harding’s first term and then winning an election of his own, from 1923 to 1929. This is a very auspicious time in the cultural history of the country: a huge prosperity boom between the two world wars, the blossoming of jazz and art deco, really the beginning of cinema, and women’s suffrage all occurred during Coolidge’s reign. You might assume from the pretty radical changes in the tone of the country that Coolidge would be a forceful liberal. He was not.

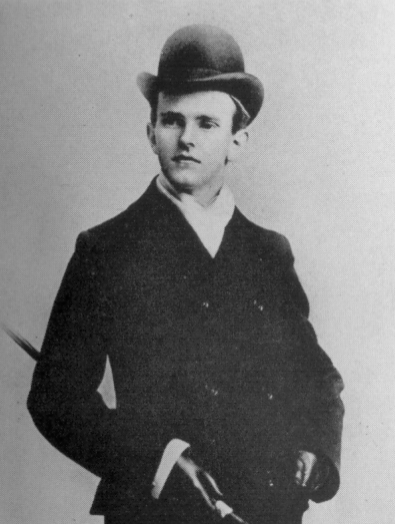

Young Calvin, at Amherst College. (Photo: Public domain/Wikimedia Commons)

In fact Coolidge was known as one of the most severe and austere presidents. Highly religious, he was in some ways kind of a throwback, a Puritanical man out of time. Despite the luxuries blooming around him, Coolidge preferred the electricity- and phone-free cottage in which he was raised. He appears to have hated glad-handing and, to be frank, does not appear to have really liked people all that much. He picked out his children’s clothes and made his sons wear formal tuxedos to dinner every night. He did not speak at all at most of the events he was forced to attend; a biographer notes that he was once asked why he bothered to even attend, given that he maintained such a sour expression and refused to speak to anyone. He replied, “Got to eat somewhere.”

During his vice-presidency he gained the nickname “Silent Cal,” and gained a reputation for basically sitting by and doing nothing. (This reputation turned sinister, sometimes: first in 1925 when a massive, revitalized Ku Klux Klan rally was allowed to take place in the capital, and then later, when the economy crashed into the Great Depression a mere few months after he left.)

The rare sight of Coolidge addressing a crowd in 1924. (Photo: National Photo Company/Wikimedia Commons)

There are a bunch of very weird anecdotes about Coolidge calling advisors into the Oval Office and then just…staring at them, silently. In an interview with advisor Bernard Baruch, he said his technique for dealing with visitors who wanted something was to simply let them talk themselves out. “Well, Baruch,” he said, “many times I say only ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to people. Even that is too much. It winds them up for twenty minutes more.” Famously, when he died, Dorothy Parker said, “How can they tell?”

He deflected questions mercilessly and, in seeming total contrast to politicians of today, showed absolutely no interest in earning the affection of his audiences. Here is a typical exchange, from Vermont History:

During the 1924 presidential campaign a newsman sought Coolidge out. “Mr. President,” he asked, “what do you think of Prohibition?” “No comment,” replied Coolidge. “Will you say something about unemployment?” “No,” said Coolidge. “Will you tell us your views about the world situation?” persisted the reporter. “No.” “About your message to Congress?” “No.” The disappointed reporter started to leave, but as he reached the door Coolidge said, “Wait.” Hopefully, the man turned around and Coolidge cautioned: “Now remember—don’t quote me.”

Yet this was actually a bizarre and extremely effective strategy. Coolidge’s relationship with reporters, far from being as antagonistic as that anecdote makes it seem, was warm and friendly. He gave more press conferences than any other president, but on his terms: questions would be submitted via slips of paper before the conference, and Coolidge would look through those and pick out which ones he felt like answering. (If there were no questions he felt like answering, he’d say so and just leave.) His answers were not for attribution, meaning they could never be used in an article, which gave Coolidge the ability to cultivate a relationship with the press corps without much risk of gaffes.

Not that he was at much risk of gaffes, judging by a report from Nieman; his replies would regularly state that he didn’t know the answer, and heavily imply that he didn’t much care. When asked about which states he expected to carry in the 1924 election, he said: “I haven’t any specific reports about any states. My reports indicate that I shall probably carry Northampton [Massachusetts, his hometown]. That is based more on experience.”

Coolidge was actually one of the country’s funniest presidents, possessing an excellent dry wit. Coolidge was known for never smiling or laughing at his own jokes, a fact which seems to have confused most people. One anecdote finds a talkative and socially prominent hostess cornering Coolidge at a party and telling him that the president must help her out: she’s made a bet that she can get him to say more than two words at the party. His reply? “You lose.”

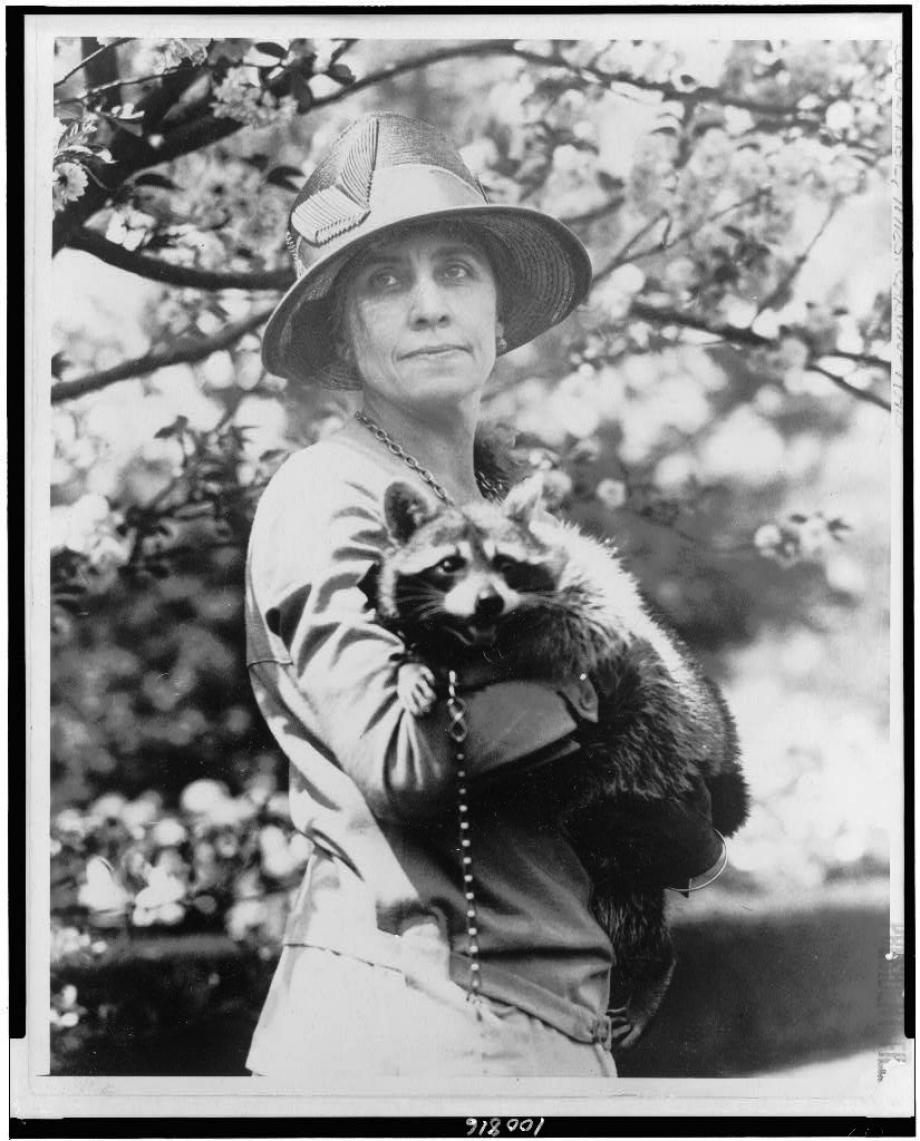

The First Lady, Grace Coolidge, was known for being quite loquacious. (Photo: Herbert E. French/Wikimedia Commons)

As part of his cultivated image of not really doing anything, he insisted on sleeping for 12 hours every night. When he woke up, the first thing he’d ask an aide was: “Is the country still there?” And he was known for playing strange practical jokes, like pressing the buzzer on his desk to call in the Secret Service and then hiding to make them think he’d been kidnapped. Or very solemnly pouring cream into his saucer rather than his teacup, waiting for all his guests to do the same for fear of misbehaving in front of the president, and then, without comment, placing the saucer on the ground for the dog to drink from.

Perhaps the 30th President would have fared better if his constituents weren’t human. His pet collection was legion. At various times, the Coolidge White House housed four cats, nine dogs, and seven birds. Even weirder is the exotics: Coolidge was gifted a black bear, a wallaby, two lion cubs (named Tax Reduction and Budget Bureau, which is a joke so dry I’m not even sure I get it), and a duiker (a small variety of antelope). Those ended up in the zoo, but a raccoon named Rebecca (who was originally given to the White House to be eaten) remained a pet in the White House, taking baths in the presidential suite. Grace Coolidge also tried to raise a flock of ducks in one of the bathrooms, but apparently they grew a bit too large and also ended up in the zoo.

Grace Coolidge with their pet racoon. (Photo: Library of Congress)

Coolidge’s silence and seeming apathy was, of course, a ploy; biographers note that he did not much like his speaking voice, and so cultivated a mysterious sort of aura in which anything he said would be taken much more seriously because his speeches were so rare. It remains to be seen how history will remember Clarence Thomas’ silent ways on the bench, but the American appetite for introverts hasn’t exactly widened. “I think the American people want a solemn ass as a President, and I think I will go along with them,” Coolidge once said. Not exactly the guy who you want to get a beer with.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook