Where U.S. Mail Went to Die

The dead letter office, circa 1926. (Photo: Library of Congress)

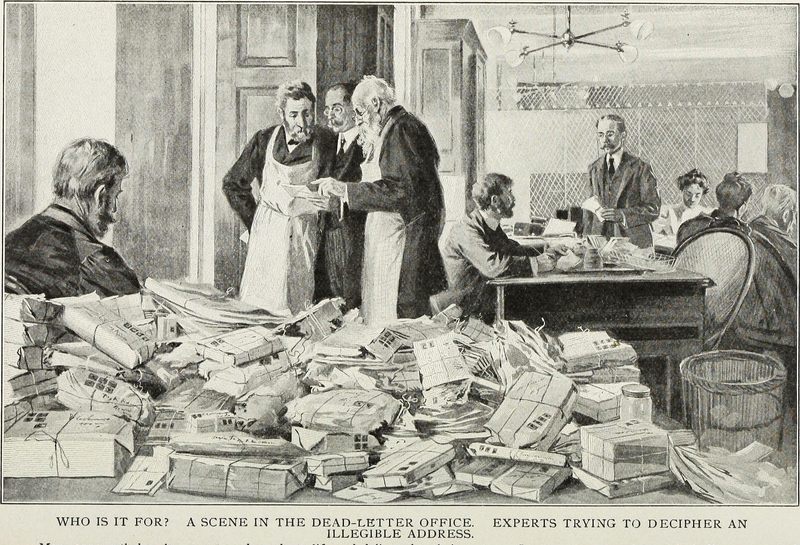

The “dead” mail arrived constantly, black bags filled with almost 30,000 letters and parcels each day. These high casualties caused only a general sense of alarm among late 19th and early 20th century Americans. Postal clerks in Washington, D.C. sorted through all letters pronounced dead, separating the truly lifeless from the merely ill. Clerks worked to decipher illegible addresses, complete vague or partial addresses, and identify the sender of a letter with insufficient postage so that the item could be returned and posted properly.

When a letter or parcel really and truly died, clerks recycled the paper, sorted the packages’ contents, and displayed some of the strangest and most notorious items in a small museum. As early as the 1850s, visiting the Dead Letter Office and its makeshift museum was a wildly popular activity for tourists to Washington, D.C. Travel guides and popular writers encouraged visitors to witness the scale of the United States government by visiting the Pension Office, Patent Office, and Post Office Department.

Items stacked up at the Dead Letter Office, 1922. (Photo: Library of Congress)

In contrast to the fictional Dead Letter Office clerk made famous in Herman Melville’s story Bartleby the Scrivener, descriptions of the DLO noted that the post office staff was much friendlier and more welcoming than their counterparts in the Pension Office. In part, this feeling may be the result of the Dead Letter Office depending almost entirely on “feminine faculty” to decipher the illegible, incomplete, or foreign addresses on mail. In the 1890s, Mrs. Patti Collins achieved much renown through her skill at “blind reading”–making sense of the garbled addresses. The Post Office Department assumed that women, and a few clergymen employed in the task, would be more honest and discreet when opening a stranger’s mail.

Letters died in myriad ways. Sometimes, an address was so incomplete or illegible that postal clerks, and even the amazing Mrs. Collins, could not identify its destination. Sometimes the sender attached insufficient postage. Records do not indicate why a one-pound, egg-shaped package of snuff could not be delivered. Although the sender covered it with revenue stamps, to indicate that he or she paid the appropriate taxes, perhaps an address, postage stamps, or any other indication of its final destination was neglected.

At other times, items like pipe bombs and loaded revolvers arrived from “reckless and thoughtless persons” who showed an “utter disregard of the postal laws!” In 1903, the Dead Letter office received “a perforated tin can containing three rattlesnakes, very much alive and in fighting trim.” The staff of the DLO sent for someone “accustomed to handling such reptiles” who might chloroform them. Thinking the snakes were dead, the clerks left the snake under their supervisor’s desk. A few days later, a female visitor to the DLO looked down and “saw a rattlesnake coiled ready to spring.” Fortunately, a letter carrier entered the room at exactly that moment and threw his full mailbag onto the snake. Shortly thereafter, the clerks decided to place the snakes into alcohol and display on the museum’s shelves.

An illustration from the 1901 book Thirty Years in Washington. (Photo: Internet archive/flickr)

An astounding number of letters and packages died before reaching their destination. By 1882, the Dead Letter Office dealt with 13,600 pieces of mail each day. That number only grew and by the early 20th century, Dead Letter clerks handled well over 30,000 pieces of mail daily (about 11 million items each year). Clerks did everything they could to identify the recipient or, if that was impossible, to return the item to its sender. Only after exhausting all possible attempts to identify the recipient or sender would the Dead Letter Office clerks open a letter or parcel. If clerks found any money, they made a careful note and turned the currency over to the United States Treasury. Undeliverable periodicals and reading materials were donated to Washington, D.C.-area charities. Items in parcels were sorted, catalogued, and held for a period of time. If nobody claimed them, the items were auctioned off.

The DLO became such a popular tourist destination, its shelves lined with so many interesting and unusual items, that the department established a proper museum to keep tourists from pestering the busy Dead Letter Office clerks. An exact date for the founding of the museum is difficult to pin down, but there was certainly a room dedicated to public display by the 1870s. Never a formal, curated collection, the museum represented a labor of love taken on by various anonymous members of the Post Office Department’s Dead Letter Office. The museum housed a motley combination of items that represented both the Post Office Department’s history and the innumerable strange objects that passed through the Dead Letter Office each year.

In 1899, the Post Office Department moved all its operations into the old Post Office Pavilion (the building is still standing and will soon become a Trump Hotel) at 11th St and Pennsylvania Ave. Here, visitors could see their government at work, wonder at the skill of so-called “blind readers,” and marvel at the odd items sent through the mail.

The old Post Office Pavilion, c. 1910. (Photo: Library of Congress)

One writer described the overall appearance of the museum as, “more of a pawnbroker shop than anything else.” Others described the unique mix of objects as, “the contents of the witches cauldron in MacBeth.” And one writer for a Montana newspaper described it as resembling “the handiwork of the inmates of a lunatic asylum.” This jumble of objects included “all manner of watches” and jewelry, baby clothes, gloves, razors, firearms, playing cards, toys and dolls, musical instruments, Bibles, snuff boxes, medicines, dried fruit, bones, human hair, and even a “rather old and musty” fruit-cake. What might have at first appeared to be a random collection of the strange and noteworthy would, on second glance, make perfect sense. For example, a revolver on display was said to “stand guard” over the collection of rings and other jewelry.

Occasionally, people reunited with lost items during a visit to the DLO Museum. In 1890, a gentlemen discovered his false teeth while visiting the museum. He sent the dentures off to his dentist for repair “but lost track of them entirely.” In the intervening months, he purchased new dentures, so his false teeth remained on display in the museum. Perhaps more common was individuals who could prove their claim on lost jewelry, family Bibles, and other household items.

The macabre and somber also graced the museum’s display shelves. In addition to a few skulls, an 1890 newspaper article described “a little envelope” containing “a lock of dark-brown hair. An inscription, in a nervous hand, reads: ‘This contains my hair. Charles Guiteau.” Apparently, Guiteau, who assassinated President Garfield in 1881, dropped a lock of his hair into the mail for a wealthy woman. She declined to receive the gift and the hair, which “resembled bristles shared from the spine of a pig” rather than human hair, made its way to the DLO Museum. The museum also held a piece of wood from the floor where Jesse James was killed.

A Dead Letter Office sale, c. 1920. (Photo: LIbrary of Congress)

Perhaps the most somber items on display in the DLO’s museum were thousands of photographs of Civil War soldiers. Women wept over the album as they searched for a trace of their husbands, fathers, brothers, and friends lost during the Civil War. Occasionally a visitor did find the image of their loved one and was allowed to take the photograph home with them. Most of the photos remained unclaimed, however, and served as a kind of informal memorial to the Civil War’s dead.

The DLO Museum also preserved the Post Office Department’s history. A favorite item included a mailbag slashed and “covered with blood” when Native Americans attacked a mail carrier in the southwest. The museum also displayed an entire stage coach, model ships, and a number of life-size figures showing postal uniforms from around the world. Many of these objects are now in the Smithsonian National Postal Museum’s collection.

The Dead Letter Office Museum closed in 1911 and most of its contents were transferred to the National Museum (soon to become the Smithsonian Institution). As the Smithsonian began to group its collections into individual museums, items from the DLO Museum transfer were split up–some went to the Natural History Museum, some to the National Postal Museum when it opened in 1993, and still others have been deaccessioned over the past century.

The growing volume of mail, and the associated growth of dead letters, required the decentralization of Dead Letter Office operations. In 1917, Congress granted the Post Office Department the authority to open branches in several cities, including New York, Chicago, San Francisco, San Juan, Puerto Rico, and Honolulu. Dead parcel branches, which handled the undeliverable packages, opened at the same time in cities like Atlanta, Boston, New Orleans, Omaha, and more. In 1994, the Dead Letter Office changed its name to the much less catchy Mail Recovery Center.

The United States Postal Service still handles many thousands of dead letters each year. Today, all undeliverable mail ends up at a single Mail Recovery Center in Atlanta, Georgia. Like its predecessor the Dead Letter Office, the MRC auctions off items with the revenue going to the Postal Service. The MRC does not sell items individually but as large groups. In 2013, buyers bid on a huge basket of keys and entire tractor trailers filled with books.

Unfortunately, you will not be able to witness a bidding war for a group of musical instruments or unopened boxes a la Storage Wars. The Postal Service now contracts with the website GovDeals.com to run the auction online.

Join Obscura Society DC for a morning of Dead Letters on Sat., Oct. 31.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook