Found: Two of the Quarries Responsible for the Megaliths of Stonehenge

And evidence for how the massive stones were removed.

In 1923, British geologist Herbert Henry Thomas published a now-infamous study on Stonehenge, in which he claimed to know the precise location where the prehistoric architects had quarried the stones used in the massive monument. Turns out he was way off.

In a recently released study published in Antiquity, a team of archaeologists and geologists have reported the exact location of two of these quarries in western Wales. Stonehenge is made up of several different types of rocks collectively called “bluestones,” which have long been known to have come from somewhere in the Preseli Hills in Pembrokeshire. However, the researchers (who have been excavating the area for eight years) now believe they know more precisely where this megalith quarrying took place 5,000 years ago, and how it was done.

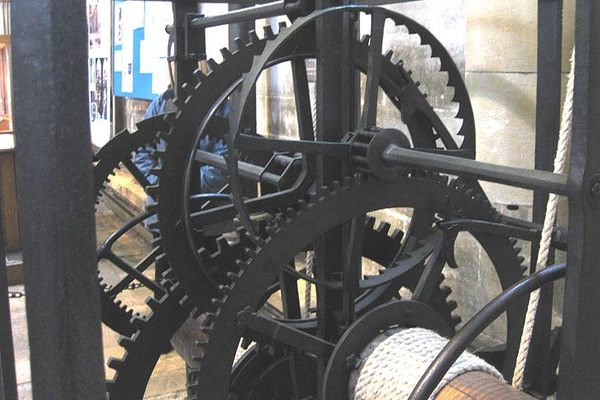

The radiocarbon dates from charcoal from both quarries show that the stones were extracted around 3000 B.C., which lines up with the first stage of Stonehenge’s construction (when bluestones were erected in the Aubrey Holes) and with previously found dates for when people were buried near the Neolithic monument. Additionally, researchers found tools such as sharp hammer stones and stone wedges that appear to illustrate how the quarrying was performed. In a stroke of early engineering genius, the stone wedges were likely used to maneuver naturally occuring vertical pillars off of the parent rock by creating space between “joints.”

These quarries sit about 180 miles away from Stonehenge, which is much farther than initially reported by Thomas in 1923. Mike Parker Pearson, who studies British prehistory at University College London’s Institute of Archaeology, and led the project, says that this “shows an unusual degree of connectivity and unity between different tribal groups in the west and east of southern Britain, uniting to build Stonehenge despite their geographical distance apart.” Previously, scientists flirted with the idea that the early builders may have transported the bluestones south to Milford Haven and then brought them to Stonehenge’s location by water. But now, since both quarries are located on the hills’ north side, Pearson and his team think that people probably carried them east over land instead. “It is making us think that this was part of a coordinated and unified operation that extended across southern Britain and that Stonehenge’s purpose was to unify the two cultures (east and west) of Neolithic Britain,” he says.

Richard Bevins of the National Museum of Wales is one of the two geologists involved in the study, and his work contributed greatly to pinning down the exact quarry locations. Based on his findings, he says, it’s likely that the “bluestones were first erected to form a henge by a Neolithic population in Pembrokeshire, and then as that population migrated to Salisbury Plain they literally took their henge with them.”

One quarry site, Carn Goedog, is what principally produced dolerite (diorite) bluestones, a blue-green igneous rock with white spots. Craig Rhos-y-felin, the other quarry, is responsible for the rhyolite bluestones found at Stonehenge. Rhyolite is a similarly “hard” rock, but lighter blue in color. Though both quarry sites produced rocks that made their way to Stonehenge, Bevins says, they don’t have much in common beyond that. Rocks from both locations are “very well-jointed,” he says, “so extracting a ‘pillar-sized’ monolith would be a relatively easy task.” Bevins and his fellow geologist, Rob Ixer of University College London’s Institute of Archaeology, performed “detailed whole rock chemical analysis as well as detailed mineral chemistry analysis”—specifically involving flecks of zircons in the stone, which he calls “an innovative approach.” This analysis indicated a match between the rocks at Craig Rhos-y-felin and at least one type of rhyolite at Stonehenge.

The only other known megalith quarry in Neolithic Europe is one on the Orkney Islands, where the slabs lie horizontally, not vertically. Moving forward, the team plans to look for a dismantled bluestone circle close to those quarries. Depending on what they find, it may suggest whether Bevins is right, and Stonehenge once stood elsewhere before it was dismantled and moved, stone-by-stone, to the familiar Salisbury Plain.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook