Who Really Designed the American Dime?

The controversy that has long roiled the coin world.

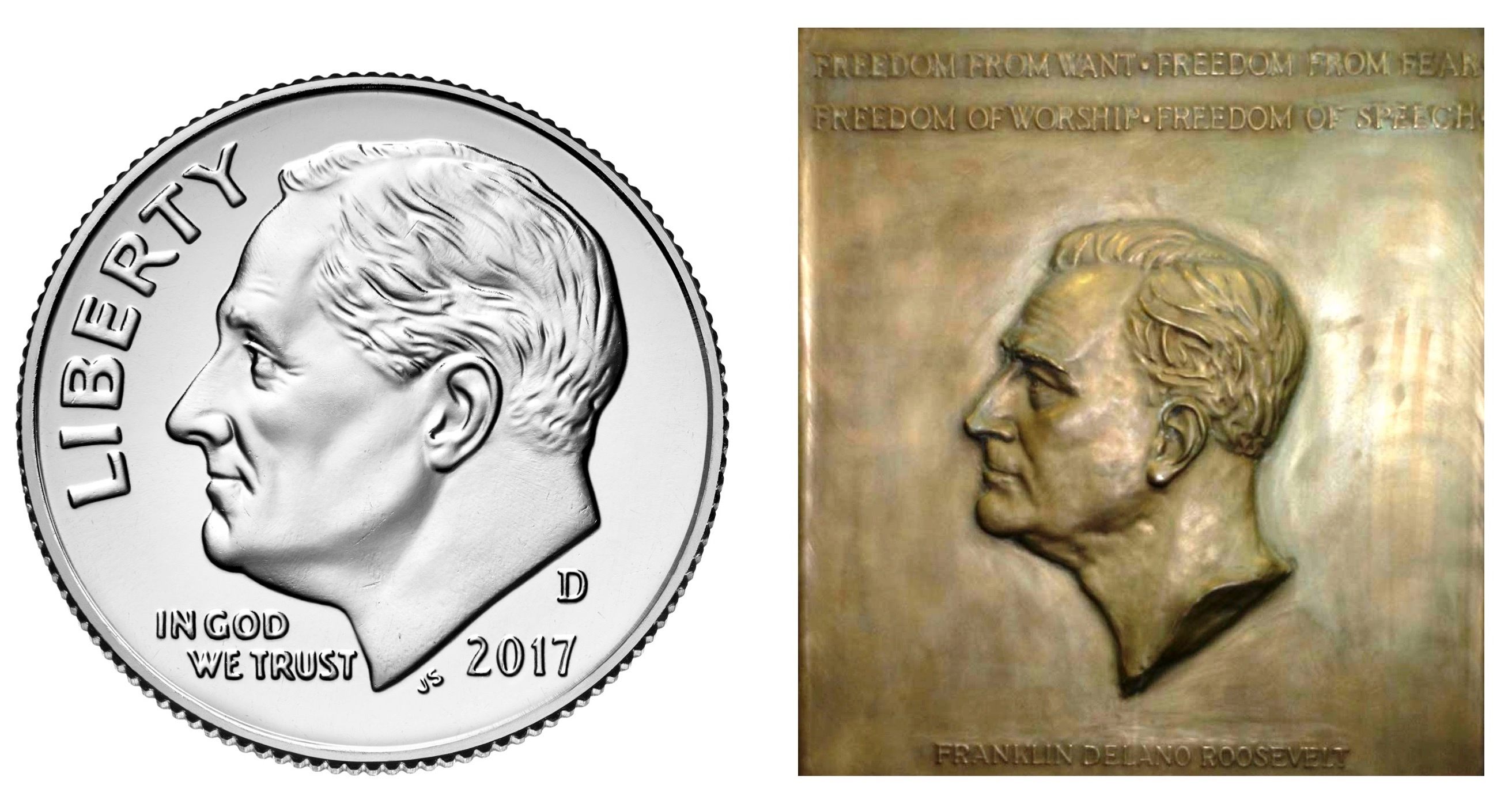

When was the last time you looked—really looked—at a dime? It is the smallest coin in U.S. circulation, so it takes a keen eye to see the very subtle “JS” just beneath Franklin D. Roosevelt’s truncated neck. These are the initials of John Sinnock, the U.S. Mint’s Chief Engraver from 1925 to 1947, who is credited with sculpting the profile of the 32nd president. However, institutions such as the Smithsonian American Art Museum—and even Roosevelt’s son—credit another sculptor with inspiring the design: Selma Burke, the illustrious Harlem Renaissance sculptor. So where is credit due? The answer is … complicated.

In 1943, 43-year-old Selma Burke won a Commission of Fine Arts competition and a rare opportunity to sculpt the president’s likeness for the new Recorder of Deeds Building in Washington, D.C. Burke, renowned for her Booker T. Washington bust, ran into some problems, since she didn’t feel that photographs captured Roosevelt’s stature. So the sculptor wrote to the White House to request a live-sketch session. The administration, to her utter shock, agreed.

On February 22, 1944, Burke met with Roosevelt for 45 minutes, sketched his profile on a brown paper bag, and engaged in a lively conversation about their childhoods. At one point, Burke said, “Mr. President, could you hold your head like this?” He invited her back for another session the following day. About a year later, just months before Roosevelt’s death, Eleanor Roosevelt visited Burke’s home in New York to see the profile-in-progress. The first lady told her, “l think you’ve made Franklin too young.” To which Burke replied, “I didn’t make it for today, I made it for tomorrow and tomorrow.”

Roosevelt died five months before the official unveiling of the plaque, in September 1945. To commemorate his legacy and his founding of the March of Dimes to combat polio, the U.S. Mint and Congress proposed engraving his portrait on the dime, which at that point held the profile of the goddess Liberty wearing a winged cap. U.S. Mint Director Nellie Tayloe Ross (the first woman elected governor, in Wyoming), tapped Sinnock for the job.

Sinnock had experience sculpting presidents in profile. For years, he taught at Pennsylvania Museum School of Industrial Art*, and in 1917 joined the Philadelphia mint as an assistant engraver. There, he designed presidential medals for Calvin Coolidge and Herbert Hoover, and later Roosevelt’s third inaugural presidential medal.

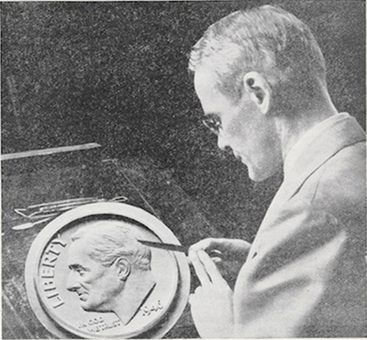

In a 1946 interview with The Numismatic Scrapbook Magazine, Sinnock said he referenced old photographs and a “composite of two studies (sculpted in relief)” of Roosevelt for his work on the dime. He also sought “the advice and criticism of two prominent sculptors” who specialized in relief portraiture before submitting his final sketch to the Commission of Fine Arts on October 12, 1945. The new Roosevelt dime rolled into circulation the next year to much celebration—and controversy.

The dime’s most vocal critic was Burke. She claimed that the dime bore a striking resemblance to her portrait. Edward Rochette, former American Numismatic Association president, supported her argument, and went a step further, suggesting that the reverse of the dime was also inspired by the Four Freedoms sculpted into Burke’s plaque, though it’s not entirely clear how.

According to Rochette, Sinnock allegedly had also taken undue credit for the design of the Sesquicentennial of Independence half-dollar coin, which he sculpted based on sketches by another artist, John Frederick Lewis, after Sinnock’s own designs were rejected. Burke believed the administration change after Roosevelt’s death and her political affiliations were reasons her claims were dismissed. When she demanded an investigation into Sinnock, Burke said the FBI investigated her instead. Mooresville Museum president David Whitlow and Andy Poore, a local historian from Burke’s hometown in Mooresville, North Carolina, confirm Burke’s sentiments about the FBI. Under J. Edgar Hoover’s direction, Whitlow states, “the FBI was investigating everyone,” including many artists. Burke was also clear that she believed racism played a role. In a 1994 interview with journalist Steven Litt, she said, “This has happened to so many black people.”

Sinnock denied Burke’s accusations, and died just a year after the coin was issued. Years later, debate among numismatists continues. Some credit Burke unequivocally, while others have conducted side-by-side comparisons to suggest significant differences between the sculptures, particularly in Roosevelt’s nose and hair.

U.S. Mint officials cite Sinnock’s previous Roosevelt work as evidence that his initials on the coin are warranted. Brenda Gatling, a former U.S. Mint public spokesperson, told Litt that “both Ms. Burke and Sinnock conducted live sittings with the president” for their designs. Current U.S. Mint Curator Robert Goler states that, according to archival records, Sinnock began sculpting Roosevelt in 1936 for “a presidential medal,” and that he “used that particular design of Roosevelt multiple times between then and the president’s death in 1945, and it’s the same the design” on the dime. (Though the 1936 medal and dime profiles face opposite directions).

Burke continued sculpting, founded the Selma Burke School of Sculpture in New York and the Selma Burke Art Center in Pittsburgh, and was honored with the Women’s Caucus for Art lifetime achievement award in 1979. Even without credit for the dime, Whitlow says, “she was great in her own right,” and Poore concedes that “Sinnock was a talented artist.” But even until her death in 1995, Burke held on to her conviction about the dime: “Everybody knows I did it.”

* Correction: This story was updated to correct the school at which Sinnock taught.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook