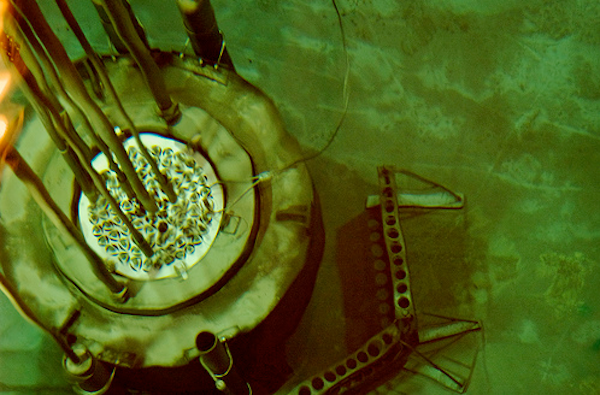

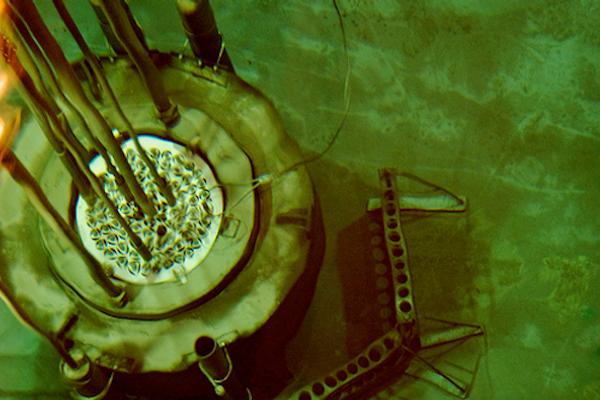

Who Put These Undergrads In Charge Of A Nuclear Reactor?

The Reed College nuclear reactor. (Photo: Sarah Brumble)

Three years ago, as Ilana Novakoski was settling into her freshman year on campus at Reed College in Portland, Oregon, she saw “the most bizarre poster I’ve ever seen.” Written on it was a question that made little sense to her: “Do you want to be a nuclear reactor operator?”

Intrigued, Novakoski investigated, and discovered the poster was real and the question legitimate. As she was told during a tour of the reactor—led by a purple-haired man in a wizard hat—the liberal arts college is home to the only nuclear reactor in the world run by undergraduate operators.

The reactor, established in 1968, is used for research and analysis, both by students at the 1,400-person college and on behalf of outside agencies. It uses a process called Neutron Activation Analysis, in which a sample—liquid, solid, or gas—is placed in the reactor and made radioactive by being bombarded with neutrons. The elements of the irradiated sample each then emit distinctive gamma rays. By measuring these gamma rays, an experimenter can identify what elements are in a sample.

This can be useful for things like analyzing rock samples and identifying contaminants in an industrial sample, but also has surprisingly broad applications outside the physical sciences. It’s ”great for artifacts,” says Margie Oxley, a reactor operator and history major studying ancient China. “We had this one experiment where we had pieces of an ancient vase. By putting them into the reactor and activating certain metals, we could identify the metals and trace the trade routes that the vases went on thousands of years ago.”

Unlike Novakoski, Oxley knew about the Reed reactor before arriving on campus. Not only that, but she was “pretty obsessed with it,” she says: “I just thought it was a great idea that I could operate a reactor and not have to be a science major.”

The reactor does not tie directly into any particular area of study—there is no nuclear engineering department at Reed—but any student at the college is welcome to use it for experiments. Likewise, the reactor operator training program is open to all students. Though the majority of Reed’s 40 undergrad operators are physical science majors, there are also English, history, economics, and psychology majors.

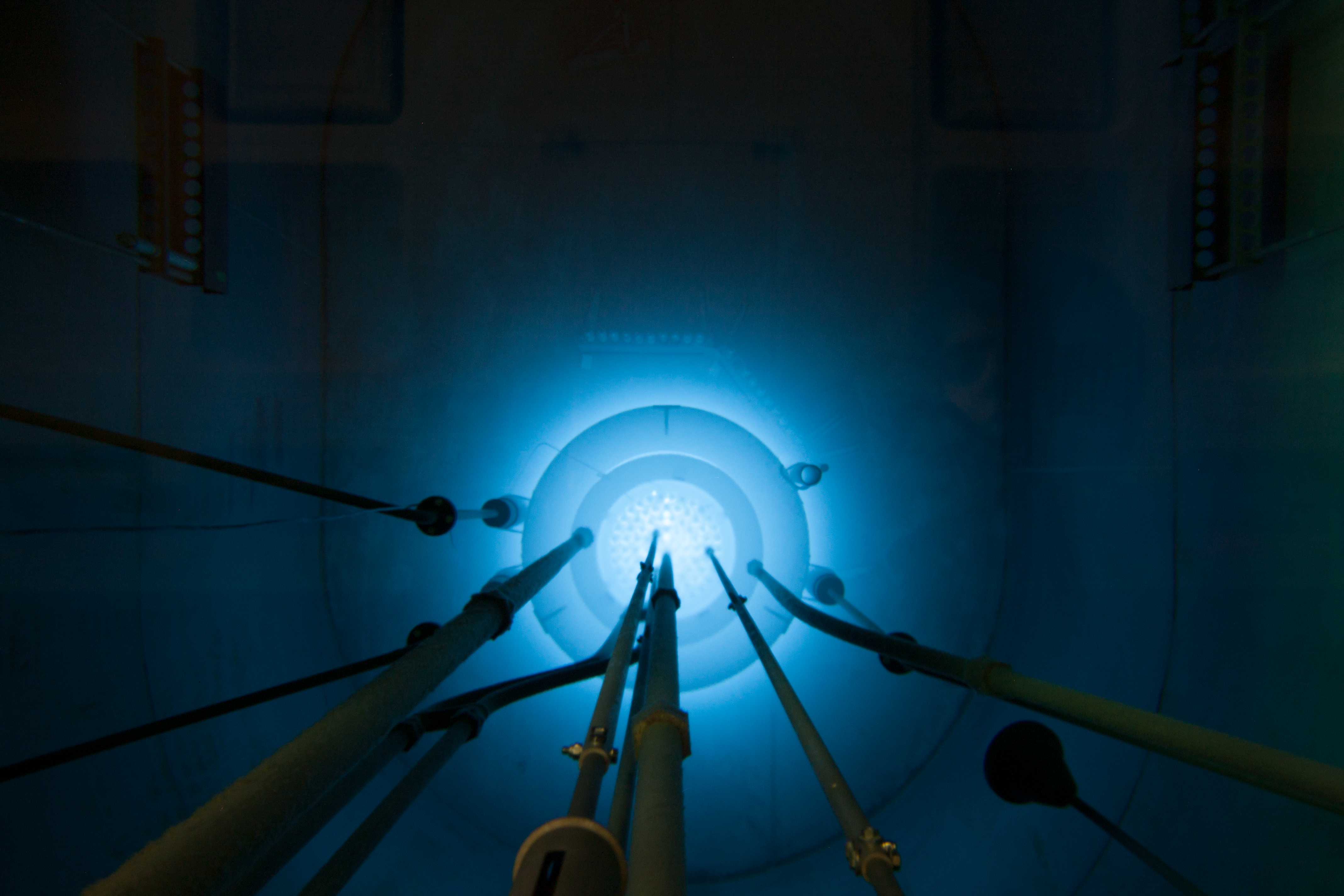

The Reed reactor pool. (Photo courtesy of Noah Lerner)

To become licensed operators, students must take a seminar two nights per week and participate in practical training tasks. After one academic year, they may take the seven-hour licensing exam administered by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, the government agency that regulates the nation’s nuclear reactors.

During their training phase, the student operators learn to irradiate samples, which can involve putting unexpected things into the reactor. “I put a bunch of my stepmother’s cosmetics in the reactor to see what sort of heavy metals were in them,” says operator Marin Sklan. Oxley and fellow operator Noah Lerner “irradiated some chocolate samples from both the local student store and from China” to see if there were any adulterants inside.

Once they have become licensed, students can conduct reactor experiments on behalf of visitors, companies, and other institutions. Hawkins recalls irradiating samples from a Nigerian uranium mine to determine whether there was a contaminant problem there. “There wasn’t,” she says. “They decommissioned the samples, so I have them sitting on my coffee table—16 tubes of water and red dust.”

“We call ourselves ‘the funnest reactor in the United States,’” says Oxley. In-jokes, double entendres, and reactor-related puns are plentiful in the “joke logbook,” which sits alongside the real logbook of standard operating procedures. The joke book contains ”infinite double entendres about inspecting fuel elements and vital area accesses,” says fellow operator Natalie Hawkins. A sophomore majoring in biology, she cites the reactor as “half the reason” she chose to study at Reed.

The playful spirit among the operators can occasionally be problematic in the eyes of the nuclear regulatory agency. The NRC, says Oxley, “isn’t always a huge fan of how much fun we have.” For example, they ”couldn’t really think of a reason why we weren’t allowed to have a rubber duck on top of our nuclear reactor pool, but they just didn’t like it.” The government agency instructed Reed’s operators to complete an official form proving the duck wasn’t dangerous. The form required a lot of work, so the students relented and removed the duck from the pool. “I feel like the NRC are our parents,” says Oxley.

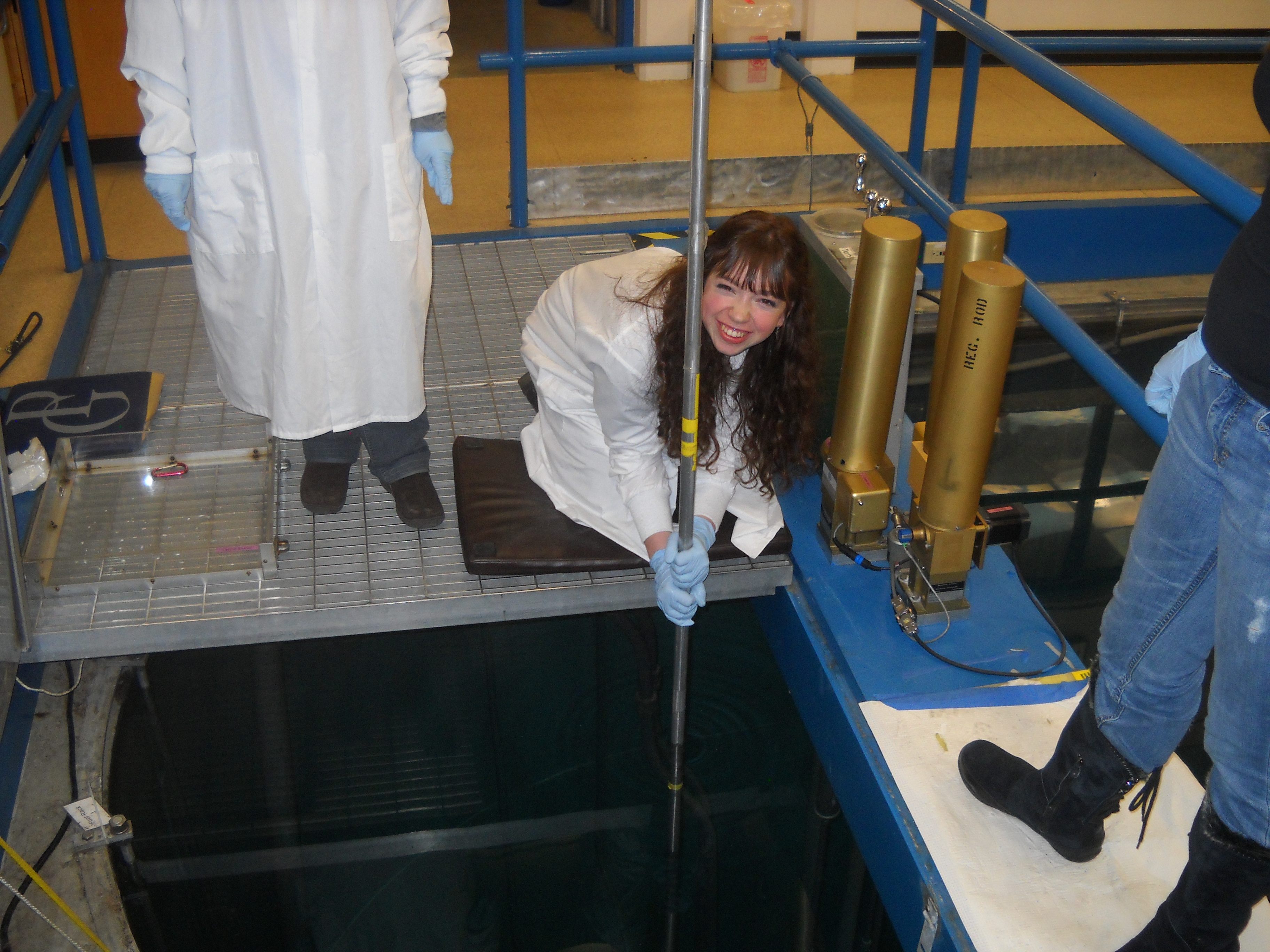

Ilana Novakoski handling fuel. (Photo courtesy of Ilana Novakoski.)

With so much irradiation happening, some visitors who take a tour of the facility wonder if it’s safe. “Everyone comes in thinking it’s going to be like Chernobyl,” says Oxley, but “it’s pretty much impossible for our reactor to melt down.” Reed says that if the worst imaginable accident were to happen at the reactor, anyone present “would have to leave the room.” That would be the extent of the fallout, both literally and figuratively.

“People are more scared of nuclear energy than they should be,” says Helena Pedrotti, a reactor operator and math and economics double major. As one of the students running the operator training program, Pedrotti says the incoming trainees have an “expectation that everyone else knows more about nuclear physics than they do, but the reality is that they all come in completely blind.” From what she’s seen, ”nobody knows how a reactor really works, even if they are a physics major.”

“The thing I find about the reactor,” says Sklan, who is majoring in English, “is that it kind of takes care of the other half of my brain.” A senior currently working on a collection of poetry that will comprise her final thesis, Sklan says that being an operator gives her “an outlet to be really analytical and quantitative and scientific.”

Reactor Operations Manager Christina Barrett at the console. (Photo courtesy of Ilana Novakoski)

Novakoski, too, has found a way to balance both sides of her brain. Initially planning to major in theater, she switched to chemistry because she enjoyed working at the reactor so much. As a freshman, she even wrote a musical devoted to the Reed reactor. It included outlandish stage directions—“have a fog machine going the whole time”; “two pounds of confetti should be used”—and featured lyrics like the following:

I can calibrate a meter

Pump the primary through a heater

I’ve memorized every sort of system chart

I can operate under direction

Perform contamination detection

But I don’t know how to fix a broken heart

When she had finished writing the 20-minute musical, Novakoski left a copy of it in the joke log book and promptly forgot about it. Two years later, she had just finished training a new group of operators. They were wrapping up a staff meeting when something unexpected happened. “All of a sudden there was this fog machine going,” she recalls. The lights dimmed, and two students, illuminated by a flashlight, began to sing. The musical she wrote as a freshman was being performed—in its entirety.

A few of the newbies had found the pages in the joke log book and decided to stage “Reactor! The Fermi Award-Winning Musical” as a thank you at the end of their training. Lerner, who wrote music to accompany Novakoski’s lyrics, says they even added a small part for her. “We brought her up from the audience as part of the show and gave her cue cards,” he says. Novakoski remembers it as “one of the highlights of my year.”

Noah Lerner and Helen Zhang perform a duet from Reactor! The Fermi Award-Winning Musical. (Photo courtesy of Noah Lerner)

Experiences like this, says Lerner, show that the reactor program has created a vibrant community of people united by a rare set of circumstances. “It’s a really neat prospect: a nuclear reactor at a tiny little school,” he says. “I’m really happy to be a part of it.”

Hawkins agrees: “When are you ever going to be given the chance to be inside of a nuclear reactor, let alone have the opportunity to mess with the structure and the nucleus of an atom?” To have had the reactor experience at Reed, she says, is to have been given ”a superpower.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook