Why Do Tennis Crowds Have to Be So Quiet?

The game’s long, weird, elitist history provides some clues.

Ladies and gentlemen, quiet please. Players are ready. Thank you.”

This is a common refrain at tennis matches, especially rowdy ones, which are not particularly rowdy by the standards of almost any other major sport. It’s a line delivered by the chair umpire, the lead on-site official. Weirdly, if you think about it, the crowds aren’t dismayed at this message. Sometimes they applaud it. “Yes,” tennis crowds seem to say. “Tell us to shut up.”

The US Open, one of the four biggest annual events in professional tennis, announced recently that it plans to move forward with the tournament in New York during the COVID-19 pandemic. As with some other sports, like NBA basketball, English Premier League soccer, and Major League Baseball, the US Open will be conducted this year without a crowd.

We’re now learning how the absence of crowd energy will affect professional athletes. How that absence will be felt in tennis is even more entertaining, because even when there is a crowd at a tennis match, they are not supposed to make any noise, save the occasional gasp.

Tennis is a deeply weird sport, a psychological, physiological, gladiatorial war of attrition. But how did silence from the crowd come to be so thoroughly associated with the sport that spectators literally applaud being told to be quiet?

Silence among tennis spectators, however well established, is not an official rule. The guidelines to Wimbledon, the most staid and stately of tennis tournaments, state: “The use of any anti-social, aggressive, annoying or dangerous behaviour, foul, abusive or racist language or obscene gestures, the removal of shirts or any clothing likely to cause offence and the climbing onto any building, wall or other structure/equipment is forbidden and may result in ejection from the Grounds.” But that’s it. There is nothing about quiet during play. That silence is not officially required is itself a tradition.

The 1923 Spalding’s Lawn Tennis Annual, a book that includes the rules of the game and recaps previous seasons, echoes this. There are extensive lists of rules, it states, that are unwritten—though they are written about there—regarding etiquette and decorum. Those include “refrain from talking loudly while a match is on,” “do not applaud or give vocal expression of your feelings while a rally is on,” and more.

The origins and evolution of tennis, like those of just about all organized sports, are messy and unclear. There are many sports from the same general family as tennis, in which a ball is hit back and forth between opponents. Often cited by historians as the grandfather of tennis is a French game called jeu de paume, or “hand game,” which, as the name suggests, was played without a racket.

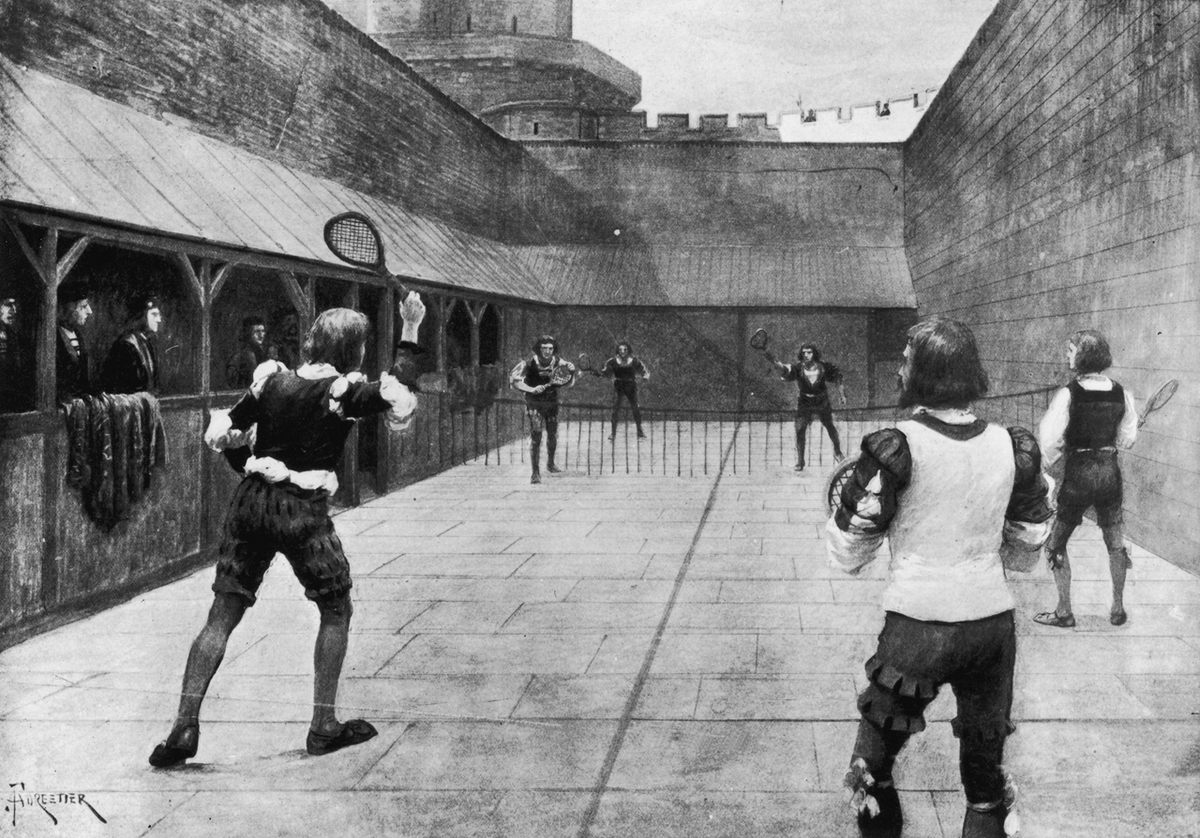

By the 1500s, a racket had been added, along with a net, and the game took off among European royals and aristocracy, especially in England, where Henry VIII was an avid player and fan. At this time it began to be known by a few different names, including the word “tennis,” which is of uncertain origin. (Some suggest it comes from the French tenez, meaning “Here, take this,” basically a variation on “Fore!” as it is used in golf, but there’s little documentation that anyone ever shouted “Tenez!” before a serve.) Sometimes what they played was called royal tennis or court tennis. That form is actually still played in extremely limited numbers, and kind of pompously called “real tennis.”

Court tennis, as it’s called in the United States, is a bonkers sport. Imagine a squash-like court—smaller than a tennis court, enclosed on all four sides, with a ceiling—and add some seriously weird shit. There are long awnings on three sides of the court, halfway up the wall, called “penthouses.” Not only can you hit the ball off of these, you have to serve off the top of them with a funky spinning lob shot. Oh, and there are a bunch of holes in the wall that you can hit the ball into, like a pinball machine, called “galleries.” And there’s an anomalous notch, only on one side of the court, called the “tambour,” off which shots can also be played. Also the racket is small, heavy, wooden, and as asymmetrical as the court itself; the head tilts to one side, as if it melted and drooped while being formed.

But this utterly eccentric sport may be key to figuring out why modern tennis audiences are silent. Because it must be played in an enclosed room, it’s basically impossible to get much of a crowd in there. The spectators sit off to one side and in a balcony, but that’s pretty much it. “The physical limitations of the space meant that no more than a hundred people could watch the contest,” says Rob Lake, a tennis historian and sociologist. Lake went to a recent world championship court tennis match, and the “arena” was at capacity, he says, maybe 60 or 70 people at most. Tennis’s origins do not involve huge stadiums or even bleachers. They involve a scattered few kings, queens, and princes in a strangely shaped box.

Court tennis was comically aristocratic. The courts were difficult and expensive to construct, the equipment has always been handmade and thus pricey, and, more to the point, the people who loved it wanted to keep it a game of leisure and affluence. Court tennis matches were social events, places to be seen, maybe to find a spouse for a wayward niece or nephew, or secure a business deal. The public—the cheering, drinking, boisterous public—was not a part of it.

Starting in the 1800s, tennis began to open up, bit by bit, while never really letting go of its roots. In 1874, Major Walton Clopton Wingfield drew up rules for a new game called “lawn tennis,” which drew on court tennis and various other racket sports. Played on an hourglass-shaped grass lawn, Wingfield’s tennis spread through his native England like crazy. Only a few months later, it made its way to the United States. The first Wimbledon tournament was in 1877, the first US Open in 1881. It was a hugely successful creation, probably helped by the fact that Wingfield sold tennis kits in a box, with everything you might need, for under $200 in today’s dollars. This tennis, the one we know and love today, with minor variations, was still called “lawn tennis” more recently than you might think. The United States Tennis Association, the national governing body, only dropped the word “lawn” from its name in 1975.

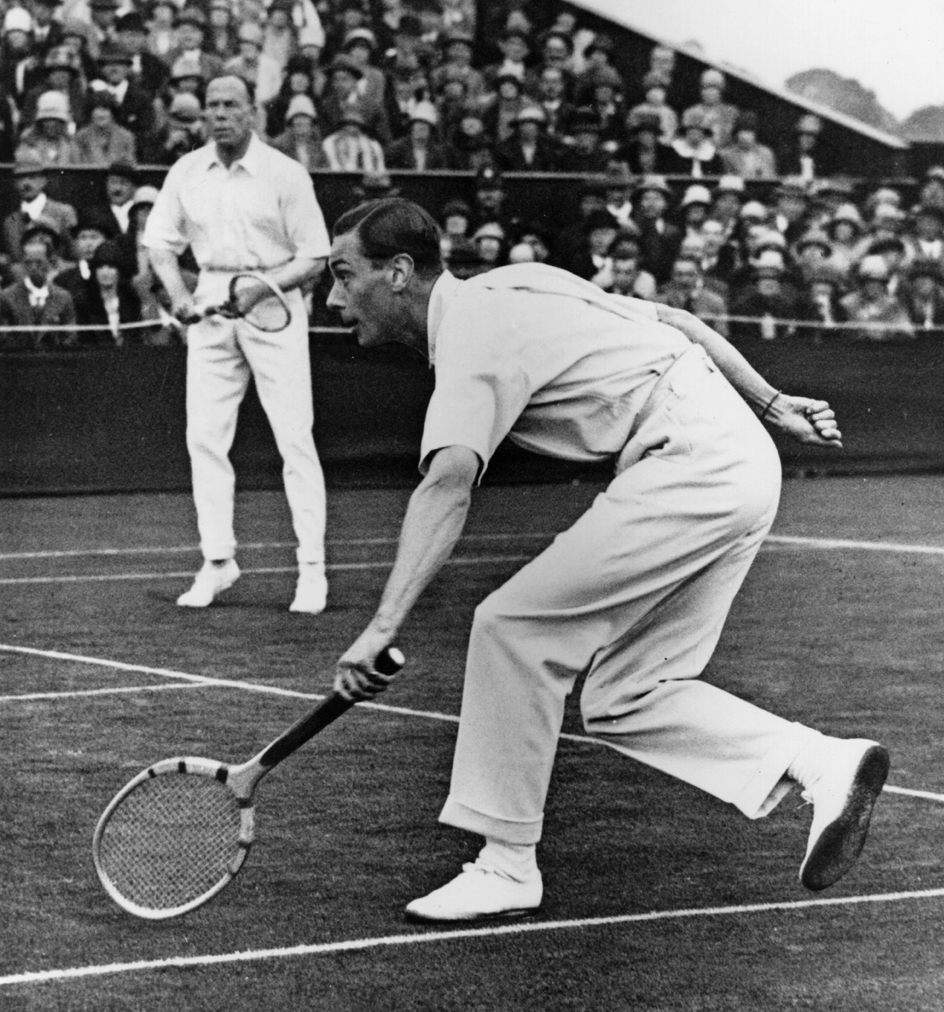

Tennis’s jump in popularity was sharp, but it maintained its elitist court tennis roots for a few different reasons. One of them is the concept of amateurism, which does not exactly mean what you might think it does. Tennis was an avowedly amateur sport, and the biggest tournaments weren’t played by professionals until 1968. Amateurism in this case doesn’t mean the players weren’t good, but rather that those who played tennis didn’t need to. It was a lark, and wealthy people would play tennis the way they wrote poetry or played the piano. It would be considered vulgar or common to make a living from it. “Amateurism at that time meant not just that you weren’t getting paid, but that you played a certain way,” says Nancy Spencer, a tennis sociologist at Bowling Green State University who has played the sport professionally. It was a gentleman’s game because it simply wasn’t taken as seriously as professional sports. There were major debates on the use of certain shots, like the volley (in which the ball is hit before it bounces) and the lob (in which the ball is hit over the opponent’s head) because these, though absolutely not against the rules, were considered unsportsmanlike. Hitting a lob, for example, makes your opponent look foolish, since he or she has to turn around and scramble backwards and make an awkward return. Obviously it’s useful in some cases if your aim is to win, but then the aim wasn’t to win, at least not at the cost of bad, undignified form.

“It was never supposed to be something that people took seriously, which is reflected in the way people played and the way they spectated,” says Lake. To play tennis at all, and even to play it well, was a sign of wealth and breeding, not sweat and practice and toil. Sweat and practice and toil, in fact, were seen as deeply uncool. The 1923 book reads, “Bear in mind that tennis is an amateur sport, played for its own sake and not for profit. Most tournaments are run at a loss. The matches give pleasure to the spectators and players and your attitude toward these contests should always be governed by this consideration.” What a luxury! Nobody needs to be doing this, nobody will be materially harmed if they lose or helped if they win. The tournament loses money, because what’s money, anyway?

The audiences in the early days of lawn tennis were exceedingly tony. The US Open was played at the ritzy Newport Casino in Newport, Rhode Island; Wimbledon was located in the posh London suburb of the same name. The New York Times and other publications covered the US Open for its first few decades, but were more concerned with the parties, hosts, and celebrities than the game on the court. In England, Wimbledon was part of the upper-class summer social circuit, alongside the Oxford-Cambridge Boat Race, the Epsom Derby horse race, and the British Open golf tournament. Tennis wasn’t for sports fans, it was for aristocrats and those who aspired to aristocracy.

“Pre–World War I, the U.S. looked to Britain as the model for behavior,” says Lake. “The British Empire was at its height and the aspirational middle-class American looked to Britain as a model not only for sport, but how they should behave.” In the early days, Britain absolutely set the tone of tennis: reserved, sophisticated, wealthy without being gaudy.

The audiences were already not particularly inclined to be noisy, because of the sport’s gentlemanly, courtly, considerate undertones. But there’s another wrinkle to the whole amateurism thing: The players were often of the same social class—and race, which we’ll get to in a minute—as the audience. This is not always the case with professional sports, where players have long been treated as assets to be bought, sold, and traded. In that 1923 book, the rules include, “Just before a match, do not try to renew an old acquaintance or express your wishes for victory to a player. Leave him alone; he has enough on his mind at that time.” The players and spectators were equals.

Professional baseball or basketball players perform for their money, as a job. Sure, salaries are astronomical today, but they weren’t always, and professional sports were long considered a fundamentally blue-collar, physical job, one that required little education or advantages in life to excel in. The Newport version of the US Open, on the other hand, sometimes gave a cask of rare wine as the championship prize.

It seems likely that with the absence of need, or incentive for victory, nobody really cared much about tennis as a sport. The result? Be quiet while a player is serving. He’s a Harvard man! A person of means! Just like us! Be nice and help him out with some quiet while he’s trying to serve.

Tennis did start to spread further, but it took a different route than other sports. Basketball, which was created, codified, and popularized around the same time, was invented by and embraced by the YMCA and its “muscular Christian” ethos. “The YMCA was trying to create strong, robust, Christian men, and tennis just didn’t fit into their idea of what that looked like,” says Lake. The YMCA wanted to get as many people as possible to play basketball. “It’s often considered that those sports [baseball, basketball, association football or soccer, American football, and more] rose as we ceased being agrarian, and that sports conferred manhood, collaboration, and teamwork,” says Joel Drucker, a tennis journalist who was named historian-at-large by the International Tennis Hall of Fame (which happens to be in Newport). Tennis has none of that. It’s a one-on-one (or two-on-two) sport, with no physical contact. It has always been an oddball among the other major sports.

Tennis requires land, at the time carefully manicured land, and is a terribly inefficient use of sports space. At most, four people can play at once, usually only two, and the space has little use beyond the game. Basketball can be played on any hard surface, needs only a single basket for casual play, and can easily be played by 10 people in a space that’s roughly 50 percent smaller than a tennis court. Baseball can be played in a field or on a street. Soccer or football are at home nearly anywhere, on any surface, where there’s enough space to run and kick or throw a ball.

Of the sports created or codified in the late 19th century, says Drucker, “Tennis isn’t pastoral like baseball, or urban like basketball.” Tennis was essentially suburban.

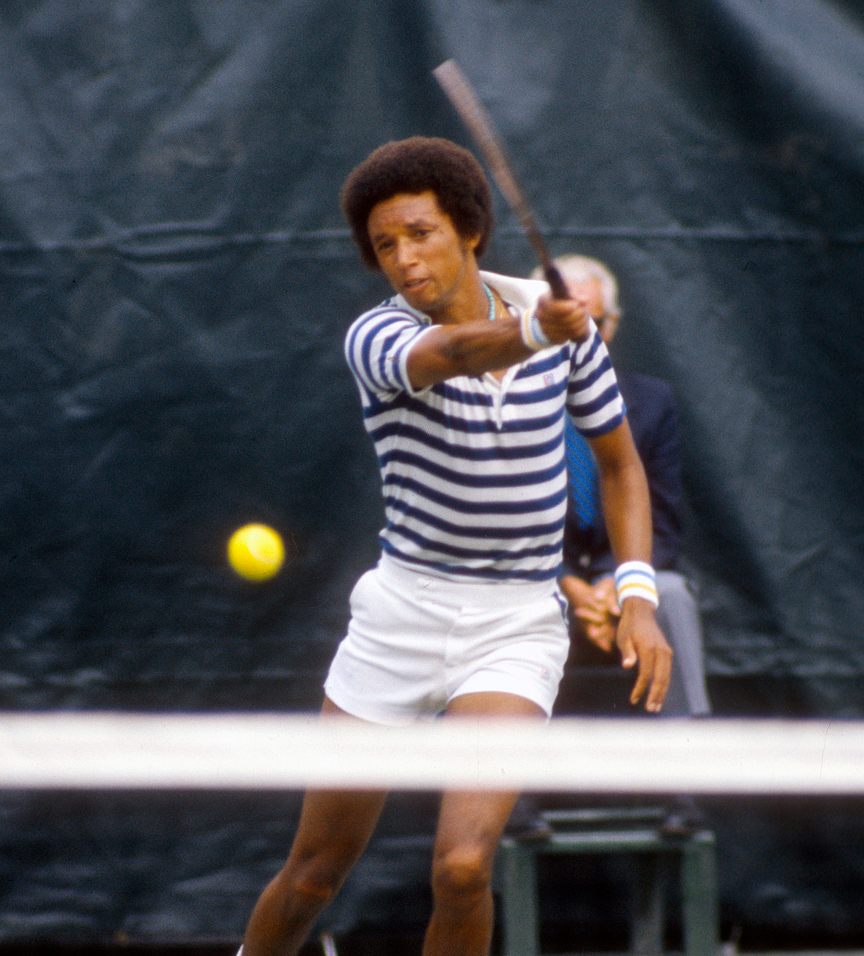

In time, tennis became a country club sport. For a long time, this didn’t just mean that tennis was popular in country clubs. Rather, players literally had to accrue points through playing at country clubs to qualify for tournaments. Those country clubs, including the Marylebone Cricket Club in London and the West Side Tennis Club in New York, held incredible sway over what the sport looked like, who played it, and how.

Technically speaking, the tennis organizations that put on the tournaments did not allow discrimination. It was the clubs that did that, effectively barring Black and Jewish athletes from its highest levels. It took the mayor of New York City and Eleanor Roosevelt to force the West Side Tennis Club to end its discriminatory policies—in the 1950s. These policies had allowed tennis to stay what it had been: an activity, not a sport, for suburban white people. (Women, it’s worth noting, have been a more significant and accepted part of tennis for longer than in any other sport. The biggest tennis stars in the world, from Suzanne Lenglen in the 1920s to Serena Williams today, have often been women.)

As a whole, the powers that controlled tennis wanted to keep it the way it was. “Tennis never had, from a leadership perspective, people who were particularly keen for it to become a mass sport,” says Lake. It wasn’t until the first decade after professionals were allowed into the tournaments, in 1968, that tennis opened up to the masses. The introduction of hard courts, which were inexpensive to build and maintain, along with the new popularity of the professional version of the sport, meant that parks and schools across the country started constructing public tennis courts—around 250,000 in the United States, these days. But the inefficiency of space still meant that it was best suited for the suburbs—and more of its unspoken standards and traditions have continued, even if they’re almost relic-like.

Take Wimbledon, which is today constructed and marketed as a posh, extremely English summer event, with champagne, strawberries, bowler hats, green grass, and a participant dress code that allows any color, so long as it is white. “It’s not the reality of how Britain is,” says Lake, whose accent betrays a major chunk of his life spent in England. “It’s kind of how Britain wants to be thought of, historically. It’s kind of a fabricated reconstruction.” When people go to Wimbledon, they’re participating in this playacting of “tennis in an English garden,” which is a phrase Wimbledon actually used for a long time. It is, as it has always been, a place to be seen and perform the genteel English tradition.

But the crowd there, as elsewhere, is a mishmash. Smaller events, even those that regularly attract all the biggest stars, are in places like the desert of Indian Wells, California, or Shanghai, or Monaco, or Cincinnati. The crowds are often diehard tennis fans who, of course, know the tradition of respect among spectators. Tennis’s lack of a clear season, jumble of tournaments around the world, and confusing professional organizations are deterrents to casual fans, outside of the four biggest tournaments of the year (Australian Open, French Open, Wimbledon, and US Open). And tickets to those events, known as the Grand Slam tournaments, are wildly expensive, making them function as elite social events as well. “It’s been a sport of privilege, so maybe there’s more resistance because people who play the sport and have that association don’t want to let go of that,” says Spencer.

This all factors into the actual reason why the tradition of being silent at tennis matches was introduced, though never explicitly, and why it remains today. There are other theories, but they’re not altogether convincing. One is that tennis requires such concentration that any distractions are excessively penalizing. While the ball in tennis does fly faster than in any other sport besides maybe jai alai, that reasoning feels like tennis exceptionalism. Silence is, of course, helpful for focus, and would also be when facing down a 100-mile-per-hour fastball, shooting a critical free throw, being heard in the huddle, or taking a penalty kick. But players in those sports don’t get that privilege. Tuning out the noise or, better yet, feeding on it, is something they must learn to do. In certain tennis tournaments—the Davis Cup, for example, or World Team Tennis—there is more crowd noise, and players who have grown up and trained with silence find it annoying—but only until they get used to it.

Another theory is that players need silence to hear the sound the ball makes coming off an opponent’s strings. The ball is coming so fast—140 miles per hour, sometimes—that players need all the information they can get. It’s true that the ball makes different sounds when hit with different spin or force, but it’s not clear that that information is required for high-level play. One study looked at whether grunting (an oft-maligned aspect of, usually, the women’s game) affects opponents. It didn’t seem to distract opponents at all. Players often insist that sound is vital to their play, but there’s no research to confirm that. Regardless, as with concentration, it’s surely helpful to hear that stuff, but just as it would be in any sport. It’s not that other athletes wouldn’t appreciate silence in some cases, it’s that only tennis players actually get it.

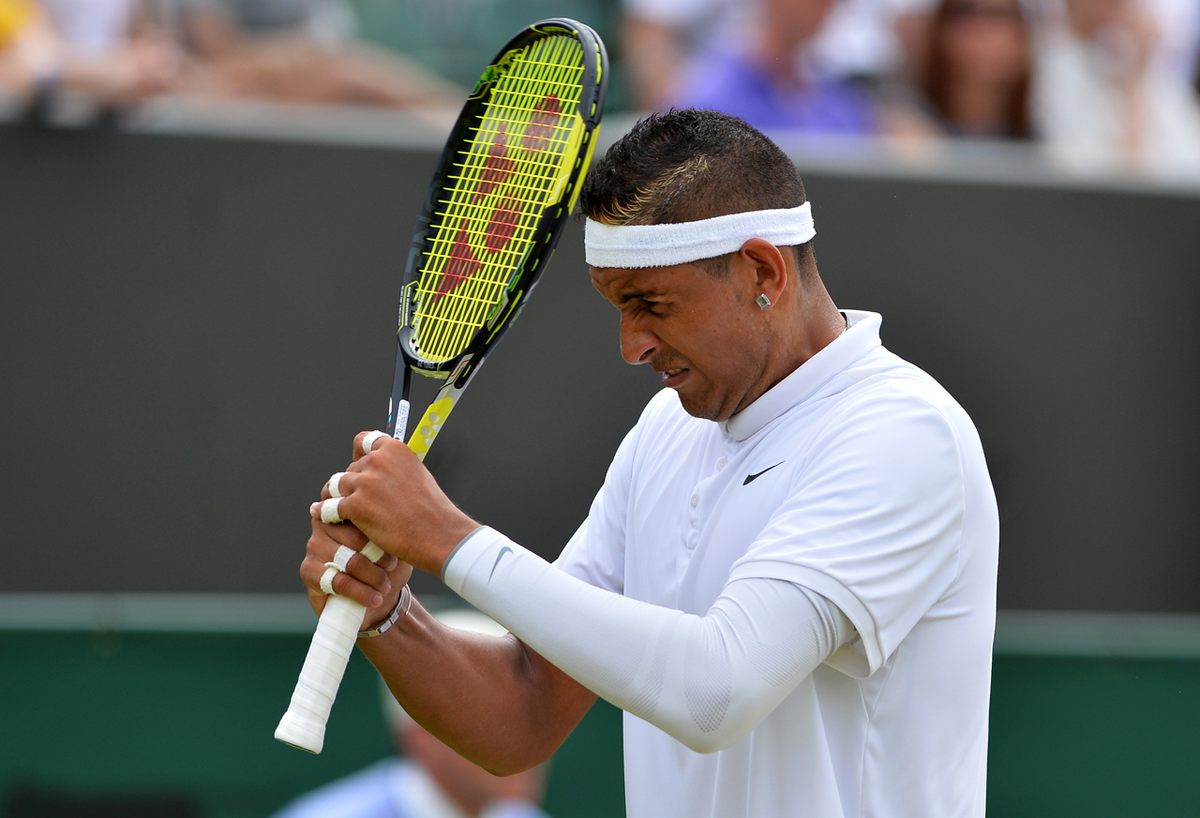

One other reason for silence that is offered, and one that I happen to like (taking into account the aristocratic roots), is that tennis as it is played today, is an unusual, slightly deranged sport. Singles players (at the major tournaments, at least) are completely alone. They walk out in front of huge crowds, all by themselves. They have to carry their own equipment, their own water bottles full of mysterious colored liquids, their own bananas. They are not permitted to communicate with coaches in any way (though it’s generally acknowledged that illegal coaching, like hand signals from the stands, is common). In singles, there aren’t any teammates to talk to or lean on. Matches are not timed, and in some tournaments they can theoretically go on for hours and hours. And these are not amateurs playing for fun and wine casks, they’re world-class athletes who’ve spent their entire lives training mentally and physically to balance speed and power, stamina and precision, instinct and planning. This all combines to make tennis a psychotically destructive sport. “The good news is, you have space to concentrate. The bad news is, you have space to concentrate,” says Drucker. Players have visible breakdowns, hitting themselves with their racquets, destroying equipment, screaming at themselves in unhinged, self-directed monologues, or engaging in deeply personal tirades with officials. No other sport is like this so regularly. It makes for a tense, sometimes uncomfortable, extremely entertaining viewing experience.

The silence, or at least the aspiration to silence, contributes to this, partly because it is not really possible to have complete quiet in a packed, 15,000-seat stadium. The fact that silence is expected and never really achieved—just listen to the number of times a chair umpire asks the crowd to shut up—is yet another way for tennis player to get into their own heads. The slightest distraction—from the fan in the third row going to the bathroom during a point, to someone in the nosebleeds screaming “COME ON!” during a serve, to the stray, useless cell phone camera flash—can trigger a full-on meltdown. It is fun and interesting, like waiting for a car crash during a high-wire act.

All of this means that the US Open’s decision to go crowdless is much more fraught and complex than it might be for other sports. In the English Premier League, canned crowd noise was piped in, with a soundboard operator essentially pressing buttons in accordance with the on-field action. The fake crowd noise, according to German soccer league players who played with it, is weird, but probably better than echoey silence. Surely when they’re in the midst of a match, it all fades to loud white noise anyway.

Until 2020, tennis players these days do not or cannot ignore crowds, or let their antics fade into the background. Some are known for attempting to get the crowd on their side, to cheer for them and against opponents to boost their energy—but not during points. This is going to be a strange time for professional athletes, as the sensory settings of their workplaces have changed dramatically. It’s going to be a whole different kind of weird for tennis players, and that somehow seems fitting for a weird kind of sport.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook