Why Kids Find the Darndest Prehistoric Things

It helps to be curious, low to the ground, and not afraid to look a little silly.

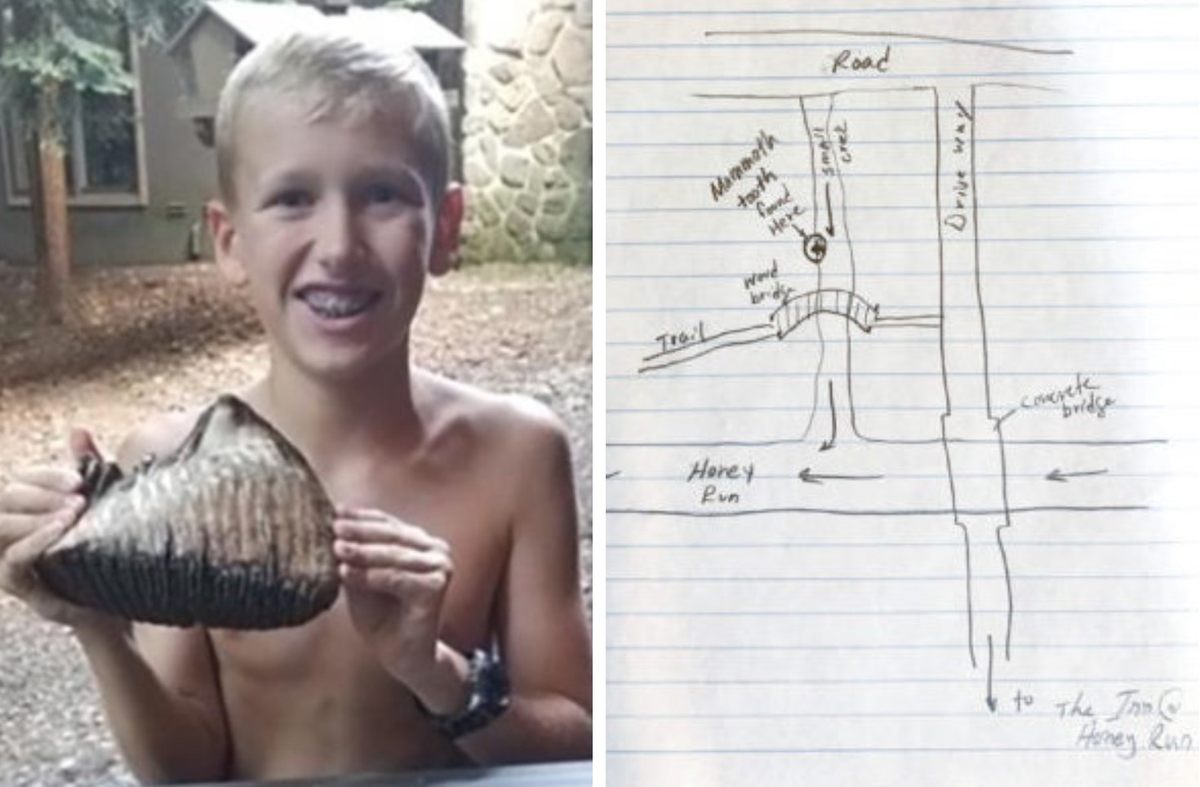

Jackson Hepner could retrace his steps easily. He knew exactly where he found the mammoth tooth.

He sketched a map on a sheet of notebook paper: roads, trails, a wooden bridge arcing over a creek. He remembered he had walked about 10 yards from the bridge, where he’d been posing for pictures with his family. He was off alone, just looking around, when he spotted it: a brown-beige, white, ridged thing, about seven inches long. “It looked like this big, lined rock coming out up of the mud,” he recalls. It wasn’t fully buried, and he easily pulled it loose with his hands. He thought it might be “a ribcage from some animal that another animal didn’t finish,” because there was some ruddy coloration that reminded him of long-dried blood. Several researchers would soon identify the object as an upper molar from a prehistoric pachyderm. In photos of Hepner and his find, the 12-year-old is cracking an enormous, toothy grin.

Hepner found the fossil in July 2019, while visiting his uncle’s inn in Millersburg, Ohio. His story made the news, but he’s hardly the first kid to find something prehistoric or just pretty darn cool. Each year brings new stories of kids finding swords or stegomastodons while they’re exploring. (Hepner himself has around 400 shark teeth in a jar at home—his bounty from several summers at Myrtle Beach, South Carolina.) When it comes to spotting fossils and other amazing things in and on the ground, kids have quite a few things going for them.

There is ample opportunity for amateur fossil hunters of any age to find something out there, if they look in the right place. “There are only so many paleontologists in the world, and we can only spend so much time in the outcrops looking for fossils,” says Bill Simpson, head of the geological collections and collections manager of fossil vertebrates at the Field Museum in Chicago. Parts of the Midwest in particular are lousy with fossils because 430 million years ago, the area was covered by a shallow tropical sea, brimming with life. Reefs stretched across portions of Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin, Indiana, Ohio, and beyond. Later, glaciers carried fossils through and deposited them along the shores of present-day Lake Michigan. Finding something big like Hepner did is relatively rare, but if you count fossil fragments, the amount of ancient stuff in the Midwest is “just about infinite,” says Paul Mayer, collections manager of fossil invertebrates at the Field Museum, who regularly examines amateur finds at the museum’s identification days.

Kids don’t have a monopoly on spotting things. The state fossil of Illinois—the so-called “Tully Monster,” or Tullimonstrum gregarium—was found by an adult amateur collector, Francis Tully, in the 1950s. (It looked a little like an earthworm, but with a dragon’s tail, a long snout and pincher jaw, and two eyes jutting off the sides of its body.) Adults working farm fields or construction projects have a good shot of seeing something in turned-up earth, but kids have certain advantages.

For one thing, they’re curious. “They ask more questions,” Mayer says. “They grab something and say, ‘What’s this?’” Many of them have keen eyesight and, frankly, they’re closer to the ground, and have fewer qualms about getting dirty and rooting around down there. “Their stature makes them closer to the target, so they’re more apt to see things we’re overlooking,” says Carl Mehling, a senior museum specialist in paleontology at the American Museum of Natural History in New York, and a regular at that institution’s identification events. Youngsters aren’t necessarily nervous about scrabbling, scuttling, or otherwise contorting themselves to get a good look at something. “For me, it’s perfectly normal to get down on all fours and go looking for things,” Mehling says. “Many collectors or adults aren’t willing to do that. Kids bumble into things more often.”

Mehling saw that firsthand in June 2015, when he was in Big Brook, New Jersey, searching for Late Cretaceous marine fossils with some museum members. A shaggy-haired 13-year-old named Braden Vande Plasse handed him a little chip of something he had found on the ground. It looked like a smashed bit of eggshell, tinted gray and speckled with white dots—easy to overlook. “What caught my eye first was that it wasn’t shaped like the other polished stones in the creek,” Vande Plasse says. “It was polished, but looked more like a pottery shard than a normal rock. It certainly did not look like any type of rock I’d learned about in science class.”

At first, Mehling wasn’t so sure. “My immediate reaction was, ‘It’s nothing,’ but I try to go through the motions, look through the lens, give it its due at least from an acting perspective,” Mehling says. He peered at it through his loupe—and his opinion changed in an instant. “I thought, ‘Holy shit, this is actually something,’” he says.

Back at the museum, Mehling enlisted some ichthyologists for a second look. After consulting with a few experts, he concluded that the freckled fragment was probably a portion of a tooth plate from a Late Cretaceous fish from the family Plethodidae. Mehling had never seen one like it in three decades of fossil hunting in New Jersey. Vande Plasse donated the fragment to the museum.

That’s not to say that kids are experts in knowing that they’ve stumbled across something great or unusual. Often, they think (and hope, and pray) that they’ve found a dinosaur. “Something bitey, pointy, huge—that’s what they want it to be,” Mehling says. With annulations on their shells, long, orthoconic cephalopods, such as Dawsonoceras, do look a bit like backbones that could have come from a dinosaur, Mayer says—but the rock formations in Chicago that yield these fossils are hundreds of millions of years too old for that. (Mayer tries to be gentle and get any disappointed kids excited about the distant past in other ways, such as explaining how different Chicago would have been at the time—“warm like the Bahamas, no Snowmageddon, no polar vortex.”)

When experts or experienced amateurs go fossil hunting, they sort of know what they’re looking for. If he’s been to a place before and knows what to expect, Mehling calls up images in his mind, like a search engine, and sifts out anything that doesn’t match (though he also stays attuned to anything that departs so markedly from those images that it just might be extraordinary). “I know my mind basically ignores all the pebbles, thrown to the side,” Mehling says, and that can restrict his ability to spot something he’s never encountered before. Kids and first-timers, however, cast a wider net, and might be more likely to spot something unexpected, Mehling says. “They don’t have the blinders.”

There’s no way to keep track of fossils found by kids to compare against ones found by adults. (The majority of noteworthy finds donated to the Field Museum, Simpson says, were found by grown-ups, not to mention the concerted effort of adult paleontologists all over the world.) But when kids do find things, it could be more likely to make the news, partly because they look so cute when they’re psyched about something. Hepner was excited about his find, but isn’t quite sure what he’ll do with it: It’s sitting on a shelf in his bedroom, “gathering dust,” he says. Down the road, he can picture selling it or making it a family heirloom.

But the lessons of his discovery and so many others are worth remembering: Whether you’re a kid or just a grown-up geeked up about fossils, keep an open mind and always be willing to crouch down for a closer look.

Did you ever make any incredible discoveries when you were young? Head over to our Community forums and let us know, or share any other thoughts or comments!

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook