Why Making a Better Umbrella Is Way Harder Than It Seems

Their design hasn’t changed in a very long time.

The inside of an umbrella. (Photo: Ralph Hockens/CC BY 2.0)

A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.

Umbrellas are a good way to protect your head in case of inclement weather.

Problem is, they’re not a perfect way. And that is made obvious by the fact that you’re sometimes hit by at least a little of the wet stuff even after you use such a device. If it gets windy (or even if it doesn’t), their structural integrity breaks down easily, exposing users to rain.

They can also be bulky, even unreasonably so. And they’re incredibly easy to forget and lose. For these reasons and others, this scenario is likely a common one: A person, frustrated by the device supposedly covering their head, thinks to themselves, “there has to be a better way,” runs to their garage, and starts working on a rethink of the device. Eventually, they form their idea, call up the big umbrella manufacturers, and go to the patent office, thinking their idea is unique. Turns out, they are far from alone.

Since 1790, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office has had a mandate to help register the ownership of products to specific people and companies.

For nearly as long, people have been registering patents for umbrellas and all sorts of other things of varying complexity.

And it has its own designation from USPTO. According to the government office, an umbrella is generally considered ”subject matter comprising an easily-portable canopy type having a cover, a stick, and a framework comprising stick-supported ribs and stretchers for supporting or shaping the cover.”

That fairly broad canvas of a design (along with the “subcombinations and appurtenances peculiar to umbrellas” covered by patent law) has been used and abused in thousands of ways over the years, especially in the name of pet owners.

Umbrellas are, unfortunately, very easy to forget. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-USZ62-11573)

(And the popularity of umbrellas isn’t just limited to the patents: The Travelers Companies has filed more than 30 trademark challenges against other companies attempting to create a logo with an umbrella baked in. “We have one of the best and most recognizable brands in the world and take seriously our responsibility to protect its value,” a spokesperson told the Wall Street Journal about its decision-making process, which has led the company to take on even tiny firms that would never hope to compete with the $33 billion company.)

In 2008, New Yorker scribe Susan Orlean highlighted the fact that the patent office received enough umbrella patent filings at the time that four people were on the umbrella patent beat in the federal government. A search of Google patents shows that, since Orlean’s article was published in February 2008, 1,617 new umbrella-related filings have gone up in the USPTO database in the “Walking Sticks; Umbrellas; Ladies’ or Like Fans” section, which is where umbrellas, fans, or other items on sticks appear.

And all those patent filings don’t seem to actually impress the manufacturers of those umbrellas. Orlean explained why:

Totes Isotoner, which is the largest umbrella company in the country, stopped accepting unsolicited proposals several years ago. One of the problems, according to Ann Headley, the director of rain-product development for Totes, is that umbrellas are so ordinary that everyone thinks about them, and, because they’re relatively simple, you don’t need an advanced degree to imagine a way to redesign them, but it’s difficult to come up with an umbrella idea that hasn’t already been done. The three-section folding umbrella, for instance, which seemed so novel when it was first manufactured, in the nineteen eighties, was actually patented almost a hundred years ago.

But those long odds and cynical comments still haven’t stopped folks from trying. In 2012, for example, a pair of Taiwanese designers took on the rain using a bold concept design it called the Rain Shield, which takes on sideways rain and avoids getting blown out of the way by wind.

(Despite the buzz it received, however, it has yet to hit the market in a meaningful way. Bummer.)

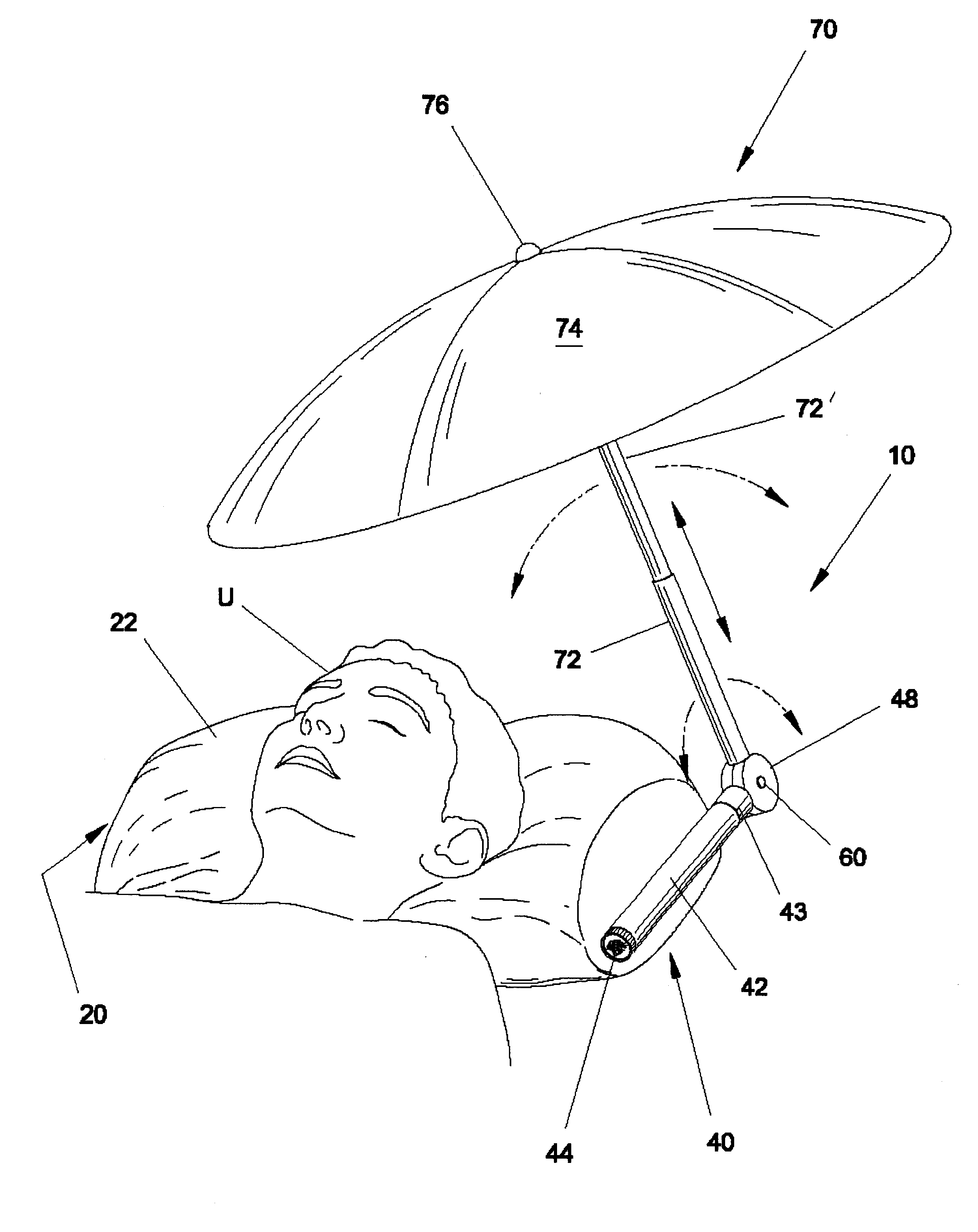

A patent for a pillow with a retractable umbrella. (Photo: Google Patents US 6711769 B1)

That’s a good idea. A lot of other ideas are terrible, of course. A few samples from some of the most unusual umbrella-related patent filings out there:

- “An umbrella sheath is usable with the lightning rod to provide shelter from rain and to demarcate an area of lightning protection. An alternative lower electrode is disclosed for physical and electrical contact with water.” — A filing for a portable lightning rod that, for some reason, comes with a built-in umbrella. The filing, when approved in 1983, was approved on utility grounds, despite a court stating, “we do not hesitate to say we would not consider using the claimed device for its intended purpose.”

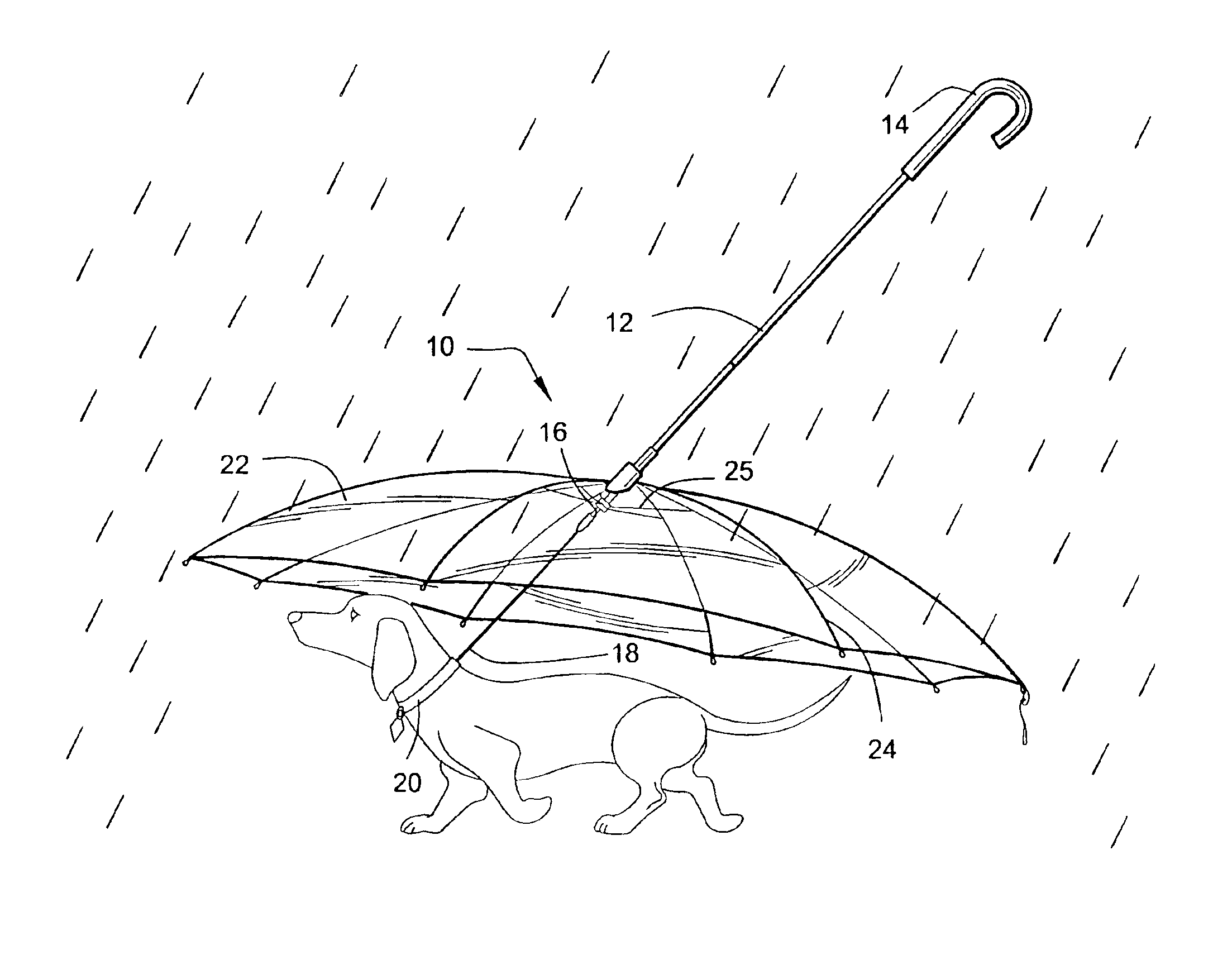

- “It will be appreciated therefore that there is a need for an umbrella to protect a pet from inclement weather conditions and which umbrella is under control of the individual walking the pet as well as enabling the pet to be under control of the individual via the umbrella and a leash in both umbrella opened and closed positions.” — A filing for a combined pet-leash and umbrella, a device that raises the obvious question: What about the owner? Multitasking two umbrellas and a dog leash sounds like a great exercise in coordination.

- “This frame is set and riveted on the brim of the hat, and supports the whole mechanism. It may also be fixed below the hat-brim.” — A filing for an umbrella hat that dates back to 1882. The innards of this thing had a number of pins that look a heckuva lot more complicated than actually picking up an umbrella.

- “The present invention relates to sunning accessories, and more particularly, to pillows with retractable umbrellas.”— A 2004 patent filing for a pillow with a retractable umbrella, just in case you were expecting something else.

- “Briefly, to achieve the desired objects of the instant invention in accordance with the preferred embodiment thereof, a helium-filled sun shade is provided for protecting individuals engaged in outdoor activities.” — A 1991 patent filing for something called a helium-filled sun shade. Sound confusing? Well, another way to put it is that it’s essentially an always-on umbrella for the sun.

You have to wonder why, in an era when we can shove a computer into a watch, we’ve struggled to improve on this basic design in a way that’s truly gone mainstream.

Sure, the basic design of the umbrella is pretty simple, and it’s somewhat built to last. And the Totes exec quoted in the Orlean piece has a point about it simply being too common for a new design to break through.

On the other hand, while everything else on our person tends to get an upgrade, whether it’s our phone, our shoes, or our personal style, umbrellas persist despite having a design that struggles at the one job it’s been tasked to do. Why is that?

If I had to pin it on a single item, it’d be the fact that people don’t want to actually pay for umbrellas. According to a 2010 report done by Accessories Magazine in accordance with NPD Group, the average price of an umbrella was just $6, a price point that suggests “disposable commodity” rather than “thing I actually care about.” (That said, the report notes that 80 percent of the industry’s profits come from umbrellas sold above a $5 price point. So maybe people who really like their umbrellas are willing to spend more?)

A patent for a combined pet leash and umbrella, filed in 2003. (Photo: Google Patents US 6871616 B2)

That issue is not limited to the present day, either. Umbrellas and Their History, an 1855 book by William Sangster, noted that a lot of innovation was happening in umbrellas at the time, but consumer interest was nonexistent in most of these innovations, as Sangster explains:

Simple as the construction of an Umbrella may appear, the number of patents that have been granted within the last thirty years might have been enormous, and a small book might be written on them, so it is of no use to attempt, in our small space, to more than mention a very few of the various improvements in their manufacture. With very few exceptions the inventors have not been repaid the cost of their patents. This has arisen, partly from the delicacy of their mechanical construction, unfitted for the rough usage to which Umbrellas are exposed; but chiefly in consequence of the increased cost of manufacture not being compensated by the improvements effected.

There are probably a variety of reasons for this incredibly frugal state of affairs—for one thing, wetness is a temporary condition—but I would say a big one is that umbrellas are really easy to lose. In fact, thousands of umbrellas get lost each year in London’s public transportation system—10,907 in 2014 alone, according to the BBC.

Sure, people should be better about keeping their stuff, but in a world where we use many of the things in our bags for multiple reasons, a bulky single-use device is going to be the first to lose out.

Charles Lim, the author of the site Crooked Pixels, suggests that it’s this disposability that makes it unnecessary to redesign umbrellas at all. In fact, he suggests (while responding to yet another umbrella redesign) that a better strategy would be to buy the cheapest, tiniest umbrellas you could find—say, from a dollar store—and carry one on you at all times.

An umbrella and stroller rain cover, c. 1913. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-USZ62-56156)

“So what do you do with an imperfect dollar store umbrella? You throw it out,” he wrote on his blog. “It’s disposable, like a condom. Most umbrellas sell for 10-20 dollars. A small Dollarama umbrella is two dollars. At that price, you can buy more than one because hey, you never know.”

When people reinvent the umbrella, often the designs are along the lines of the KAZbrella, a hit Kickstarter last year.

The company, which raised $344,000 from pledges, clearly was onto something (evidenced by the fact that some copycats quickly appeared). The umbrellas pull off a neat trick: Inventor Jenan Kazim figured out a way to produce an umbrella that traps the moisture inside—rather than leaving it outside to drip everywhere—while still looking exactly the same as an umbrella you’d see on the street during regular usage.

The problem with the idea, ultimately, is the price. When the umbrella goes on regular sale, it won’t be cheap: It’ll sell for a not-insignificant $58 a pop.

It’s a good solution, but what if it’s going after the wrong problem?

Maybe umbrellas need to be made of the cheapest, smallest, most recyclable materials one can find. And maybe we should just admit to ourselves that we’re going to ditch them after a short period of use.

In other words, maybe our inventors haven’t caught up with where the market actually is.

Umbrellas: imperfectly structured for wind and rain. (Photo: Peter/ CC BY-SA 2.0)

The other day, as I was leaving home, I forgot my umbrella. It wasn’t the first time I’ve done that, nor will it be the last. In fact, I’ll probably do it more often than not.

It was raining during the day, sure, but it was doing so in such a way where there were pockets of dryness. I ended up sticking around where I was at, waiting around for one of those pockets of dryness to show up, at which point, I skidaddled as a fast as I could to avoid another storm.

If there’s something I could redesign about the umbrella, I would make it possible to only be there when I need it, and go away when I don’t. If we figure out how to teleport stuff one of these days, the first thing we need to teleport is umbrellas into the hands of people walking out into rainstorms.

It’s a single-use device in a many-use world. But without it, we’re soaked.

A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook