Why the Race to Mars Requires Astronauts to Become Onion Farmers

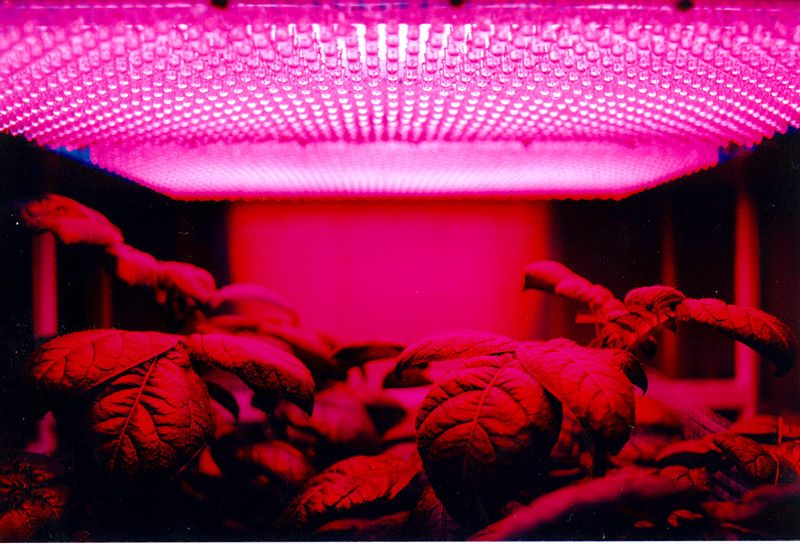

A panel of red LEDs used for illumination for a plant growth experiment with possible future application to food growing in space. (Photo: NASA/Public Domain)

When NASA astronauts tweeted this month that they had harvested a batch of red romaine lettuce aboard the International Space Station, in the microgravity of space, it was seen as an important step in the journey to travel to Mars. But it wasn’t the first time that homegrown food appeared in space.

In fact, that lettuce was nearly half-a-century in the making.

As early as 1963, Melpar Inc, an aerospace firm in suburban Virginia that was contracted by the American government during the Cold War period, began working on tissue-culture techniques in the hopes that astronauts might one day be ableto grow a meal from the scraps of a preceding one, like stem cell therapy for instant TV dinner. Nearly a decade later, the Soviets led the race to growing onions on the moon.

Bags of International Space Station food and utensils on tray from 2003. (Photo: NASA/Public Domain)

Bags of International Space Station food and utensils on tray from 2003. (Photo: NASA/Public Domain)

From 1971 to 1981, crews on the Salyut space stations attended to a greenhouse called Oasis, where they experimented with growing flax seeds, tulips, cucumbers, and fresh green onions using hydroponic techniques and others that were surprisingly low tech.

“One cosmonaut…used what he called the ‘simple peasant’s way’ to help the onions grow, carefully trimming rotting stalks as they poked out…,” reports Air & Space Magazine. “To his delight, the trimming helped the healthy stalks grow faster.”

Still, the Russians eventually abandoned the greenhouse. In a weightless environment, it’s virtually impossible for root systems to absorb water, so the onions died of thirst. And yet their efforts laid the groundwork for last week’s harvest of lettuce, which was sustained by a gravity-defying gel that may be a promising development for the future of long-term space travel, and belongs to a larger story of human survival in space.

Astronauts Thomas P. Stafford (left) and Donald K. “Deke” Slayton hold containers of hold borscht over which vodka labels have been pasted, in July 1975. (Photo: NASA/Public Domain)

Astronauts Thomas P. Stafford (left) and Donald K. “Deke” Slayton hold containers of hold borscht over which vodka labels have been pasted, in July 1975. (Photo: NASA/Public Domain)

On a million-mile journey–where your body is constantly under attack, your senses of taste and smell are diminished, and food is generally less appetizing–keeping astronauts nourished and psychologically fit is a difficult task. The trick, it seems, is to create a menu that delivers a mix of nutrition and tactile and sensual pleasures, as well as a taste of home, wherever that might be.

That helps explains why one of the first dishes that Russian astronauts and cosmonauts ate in space was borscht. A mixture of dehydrated beets in a tube that had been manufactured in a high-end factory in Estonia, it was one of the earliest attempts to replicate a beloved national dish in outer space. But that’s not all.

According to Cathy Lewis, a curator at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum who has expertise in international and Russian space programs, the dehydrated soup was also a moment to showcase the country’s cosmic ambitions.

Cosmonaut Gennady I. Padalka, Expedition 9 commander, pictured near fresh fruit floating freely in the International Space Station (ISS). (Photo: NASA/Public Domain)

Cosmonaut Gennady I. Padalka, Expedition 9 commander, pictured near fresh fruit floating freely in the International Space Station (ISS). (Photo: NASA/Public Domain)

“Yes, Russian writers like Turgenev have written about beets stew and cabbage soup, which go way back in Russian culture,” Lewis says. “But the government contracted out this factory in Estonia to make food for their cosmonauts as a sort of prestige measure, as in, ‘See, we’re going all out. This isn’t just some run of the mill Lenin-Moscow food factory.”

In fact, it was a well-known plant in Estonia that had been processing food inexpensively and well since before World War I. “It was this interesting historical mix of perceptions of prestige and food,” she adds.

Other notable menus have catered to the idiosyncratic tastes of the astronauts. In 2006, Sunita Williams became the third astronaut of Slovenian descent to go to space, but she was the first astronaut ever to take a kranjska klobasa sausage, a Slovenian delicacy, with her. The sausages had been one of Williams’ favorite foods as a child growing up in Cleveland.

Shrimp cocktail is another American astronaut favorite, “especially since they managed to make a spicy cocktail sauce that adheres to the shrimp,” Lewis says.

Sunita Williams during a spacewalk conducted on 5 September 2012. (Photo: NASA/Public

Sunita Williams during a spacewalk conducted on 5 September 2012. (Photo: NASA/Public

A NASA astronaut named Sandy Magnus recently published a diary about her attempts to cook for her Russian and American colleagues during a three-month mission over the holidays; it chronicles many feats of DIY ingenuity. “I use the foil bags that our food comes packaged in as a container for re-hydrating,” she writes. “The foil bag also comes in handy for cooking the garlic and onions.”

Magnus’ first crack at cooking in space was an attempt to season the astronauts’ canned chicken with olives, pesto, and rehydrated sun-dried tomatoes. Unfortunately, her efforts failed to soften the ”overwhelming flavor” of the original product. An experimental Christmas day feast of Russian crab salad, mesquite-grilled tuna, cornbread stuffing, and a waffle cake proved more successful.

“Food tastes are just very local, even in space,” Lewis says. “People tend to like what they’ve grown up eating. Russian astronauts, depending on where they grew up, may have different preferences than those from the Caucuses. It’s a comfort food thing.”

A close-up of a tube of Russian Borscht soup in tube, consumed by cosmonauts in space. (Photo: Aliazimi/WikiCommons CC BY 3.0)

NASA astronaut Don Pettit captures just how attached an astronaut may become to the rituals around food in his blog, Diary of a Space Zucchini, Pettit writes:

“Our part of the mission is nearly complete and the new crew will take over for us. I am a bit worried about Broccoli, Sunflower, and me. If Gardener leaves, who will take care of us? And what about little Zuc? He is now a big sprout and ready to branch out on his own. Gardener talked about pressing us. I am not sure what that means; this does not sound good.”

This need for ritual and comfort, as well as evolving perceptions of prestige, appears to be advancing food in space. According to Lewis, the European Space Agency has been pushing to make the presentation of food in space more attractive, and hopefully thus more palatable, by swapping out metal trays for “more enticing options.”

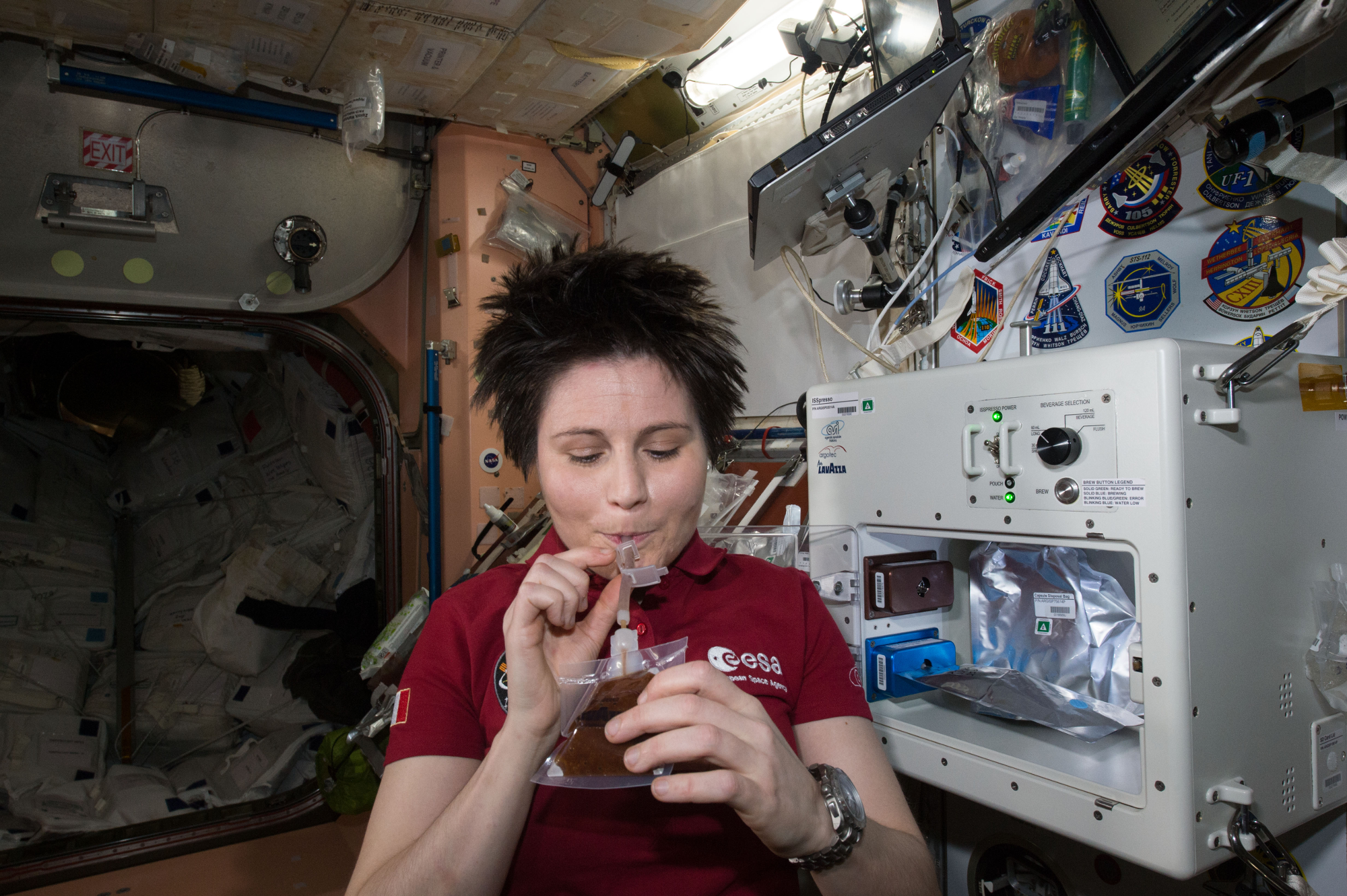

And now, thanks to the Italian Space Agency, astronauts can brew a proper cup of espresso in microgravity. The coffee cup has also been improved. Outfitted with a spout, it funnels the coffee straight into an astronaut’s mouth, allowing them to savor its aroma without sloshing hot liquid all over their faces.

Samantha Cristoforetti with an espresso in orbit, an initiative between Argotext, Lavazza and the Italian Space Agency. (Photo: Courtesy Argotec)

Samantha Cristoforetti with an espresso in orbit, an initiative between Argotext, Lavazza and the Italian Space Agency. (Photo: Courtesy Argotec)

It is a step up from the previous option for coffee drinking, which had been freeze-dried in a pouch, injected with a hot water gun, and then sucked—not sipped—from a bag.

As for fresh fruits and veggies, they have always been among the most prized items in any space station kitchen—as are spicy foods, since they tend to have more flavor, or at least give the illusion of flavor. Earlier this month, the astronauts used balsamic vinegar and virgin olive oil to dress the leaves of lettuce, before cleaning them with sanitizing wipes.

“Part of the work on the space station is establishing a foundation for long term exploration of the solar system, and there are many, many hundreds of little problems that will have to be worked out before we even consider sending humans to Mars,” says Lewis.

“As a coffee junkie myself, that’s one of the things you would have to perfect before going up.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook