The Wild Legacy of America’s Most Eccentric Roadside Attraction

Wild Bill came from a family of die-hard Republicans and clowns, and he created a destination where the only rule is “faster, wilder.”

The last big purchase that William “Wild Bill” Ziegler made was a talking tree with one bum eye. He stationed it right inside the doorway of his store, underneath a mural of a clown with a light-up red nose, across from a figurine of Charlie Chaplin, a suit of armor, and a collection of knockoff antique statues and vases. Bill used to sit behind the counter with the tree’s microphone and make it talk to customers. If they ignored the tree, he was disappointed. Any person who can pass by a talking tree is going to have a hard time fully appreciating Wild Bill’s Nostalgia in Middletown, Connecticut.

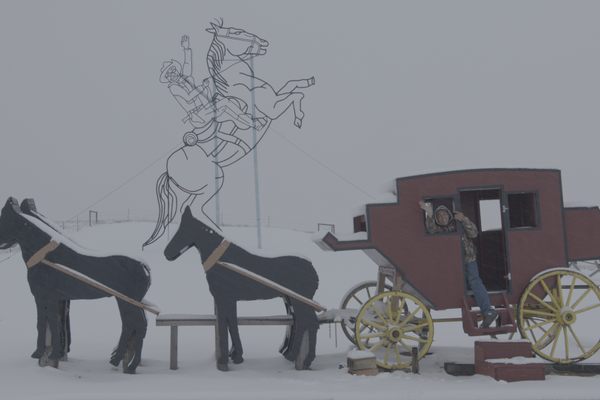

By birthright, Wild Bill was a sideshow man, and he loved anything that could make people stop and look and wonder. The store is crowded with vintage posters and bobbleheads, nesting dolls and pennants, buttons and beads. Hidden among these gems are still greater treasures—a mummified cat, Pee-wee Herman’s bike, a giant sock monkey, a whale rib, a portrait of P.T. Barnum priced at $5,000, a mechanized clown named Laughing Louie, and the Trap Man, a sculpture made of old hunting traps. In the back, there is an old Heidelberg press, and rows of shelves stacked with posters that the shop sells wholesale. Across the cracked parking lot is his book and record store, made out of an old carnival “dark ride,” in which a car on a track carried riders down a dark, twisting corridor between illuminated scenes, so the experience of browsing is more akin to getting lost in a maze. There is a funhouse, too, still incomplete, and a farm, and fields that serve as a concert venue. There are also giant sculptures and VW vans decorated at painting parties, a giant jack-in-a-box built into a silo. Oh, and there’s the sheds and the side projects, too …

“There are a lot of moving parts,” says Heather Page, Bill’s daughter, who has managed the retail store for years. Her title, if she has one, is “owner, now?” In April, at 70, Wild Bill died without warning. Now his family has to figure out how to keep everything about the place going.

Before he was Wild Bill, he was Uncle Bill, of Uncle Bill’s Buggy Whips, which manufactured specialized horsewhips as souvenirs for Texas tourists. He worked in intelligence during the Vietnam War, but when he realized that code crackers like him, who were sent out in low-flying reconnaissance planes, had a low survival rate, he decided to become “one of the klutzier black marketeers you could find,” says Cindy Ziegler, his former wife. Sent home from his station in Turkey, he finished his military career and earned a bachelor’s degree in Texas. Living off-base, he had military friends, Texas friends, and college friends, and every weekend he had a party. “The flavor would change significantly depending on which groups showed up,” Cindy says. “I would always want to see what the heck was going on.” She and Bill married in 1971, after dating for just two weeks. He had been telling her about the bachelor pad he was going to have in Connecticut, and she told him that the only way she would see that bachelor pad was as his wife.

Ok, he said. She told him he’d have to phone her dad. Ok, he said. They were married the next Saturday, after a six-day engagement, and they stayed married for forty years.

In Connecticut, where Bill grew up, they opened a series of stores (Uncle Bill’s Apple Core was once featured in a book of funny signs for its “Apple Core in Rear” placard), where they sold baseball cards, comic books, adult novelties, framed posters, helium balloons, troll dolls, and other bits of kitsch. One shop had a mini-arcade. In 1999, Wild Bill’s Nostalgia settled into its permanent home, and began its evolution into an amusement park-ish roadside attraction/oddity shop/sculpture park.

Behind the store, Joe McCarthy’s sculpture studio is still full-up from the claustrophobia of winter, when the store was always closed and Bill’s ideas gestated. Giant silk screens used by late artist Ford Beckman are suspended from the ceiling. To the side, a part of a VW Beetle is waiting to be turned into an actual six-legged insect. There are rows of small skulls pressed into strips of concrete, and a buffalo head that Bill wanted shaved because it had started to rot. “We’ll call it an albino buffalo,” he had said. A pile of rusted keys are gathered on a work bench because Bill once called Joe up to the store and asked, “Can you make a bird out of these keys?”

Joe first started working at Wild Bills Nostalgia about seven years ago, when he came to document the creation of the funhouse, which a friend of his was working on. Joe and Bill got along, and they came up with a couple of bigger ideas. “Like the Yugos,” Joe says.

The Yugos are a sculpture in which three vintage Yugo cars balance on end on three circus balls, like acrobats. It was originally named I’d Go Where Yugo Stanley Marsh 3 because it has “a Cadillac Ranch thing going on.” (Stanley Marsh 3 and the San Francisco art collective Ant Farm are responsible for the iconic Texas sculpture, which features 10 cars half-buried in the earth.) Joe didn’t know exactly where the cars had come from. Bill had one, and the two others showed up because people just bring things here. According to Heather, Wild Bill originally wanted to make a Yugo pyramid. But when Joe floated his vision, Bill immediately approved the idea—and the $10,000 or so it would take to execute. After Joe cautioned that it wouldn’t sell, Bill offered to pay him for the time it would take to create it.

It seems strange to use the word “patron,” but that’s what Bill was to Joe, in addition to “boss/buyer/seller,” who paid him for his sculpture, let him start a silk-screening business on the property, and asked, in return, for T-shirts, creativity, and a willingness to help out with whatever. Joe built a three-story installation, which he showed at the Governors Island Art Fair in 2014, on Wild Bill’s property, and together they started work on what Wild Bill came to call BoatHenge, an incomplete installation that shoots up from the field behind the record store. In its fullest execution, the boats will be surrounded by earth sculpted into waves and planted with blue wildflowers.

All of the unique sculptures at Wild Bill’s, and there are a lot of them, come from his relationships with artists such as Joe. The Trap Man and the Bear, a creature of twisted metal and bone, for instance, were created by the artist Chris Hausbeck from traps that once belonged to Bill’s father and grandfather, who taught Bill how to hunt and fish. It’s from this side of his family that Bill inherited his conservatism. He was a committed supporter of Donald Trump, which surprised people, because most men in the Northeast with long beards and hair and tie-dye-colored murals painted on their walls are not fans of the president. It’s also from that side of his family that Bill inherited his circus legacy: His grandfather and namesake, William Ziegler, was a baton twirler and clown in the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus. “They were die-hard Republicans and clowns,” Heather says.

Once you know to look for it, Bill’s affinity for his family’s circus and sideshow past is all over the property. Just inside the store, to the right, is a painting of Bill’s grandfather, balancing a flaming baton from his mouth while holding one in each hand, and a painted promotional spread featuring a bearded lady, a Fiji mermaid, a monkey boy, a mummy man, and more—characters that are mash-ups of classic sideshow figures and people associated with the store. (T.J. the Monkey Boy, for instance, is based on a friend who cuts down trees.) The disembodied heads on one of Joe’s giant sculptures—a demon-like, skeletal creature that squats over the heads, a VW Beetle, and scattered bricks—are modeled after an old piece of carnival ornamentation that sits in the store. A wooden wheel of chance that hangs nearby is similar to three that Bill’s father made and that are somewhere on the lot. That portrait of P.T. Barnum is priced at $5,000 in part to discourage potential buyers. The art of Ford Beckman, whose silk screens hang in Joe’s studio, often featured clowns. In fact, there are clowns everywhere, including a life-size Ronald McDonald. Not all of them look friendly.

Bill’s taste, too, which Joe describes as “wilder, wilder, faster, faster,” has a showman’s gestalt. He was guided by a sense of delight and of mischief. Take the mermaid on a surfboard above the store’s counter—he once arranged its shirt so that if kids stood at the right angle, they could see her boobs. He was also willing to run with an idea. “Not necessarily a good idea,” says Heather. “Anything that was an idea. It was: Is this possible? Let’s see. And he went with it.”

In her relationship with her father, Heather was often the voice of reason. When Wild Bill first mentioned the talking tree, he told her, “I had the opportunity to buy a talking tree, and I think it’s really cool.” Her reaction: We’re not doing that. He started to chuckle. He had already bought it! It was coming tomorrow! “He knew I was going to veto some of the stuff that was kookier.”

Heather has been working in her family’s shops since she was two years old, although “work” at that age might have meant putting a handful of objects into a small box to earn the right to a toy. As a preschooler, she helped customers pick out gifts for their children; she had an instinct for what a 15-year-old boy would want. Bill “fired” her two brothers for misbehavior and then ordered them to come back to the store early the next day, but he only “fired” Heather once, when she was 15 or 16. She got a job at Blockbuster. “He was devastated,” she says. “My mom had to explain to him that most people who are fired don’t come back the next day.”

She did come back eventually, and has worked with her dad on and off for her whole life. After he died, Heather’s daughter asked her, “Are you Wild Bill now, Mommy?”

She knows that she’s not, but she shares some of his qualities, including his affinity for people. “I’m hoping for myself that people will still come in, though I’m not Wild Bill, that they’ll be excited about coming and talking to me and keep that side of things going,” she says.

It’s only been a few weeks since Wild Bill died, and everyone is still processing the change. A couple of days earlier, on a Sunday, there was a memorial here, and maybe a thousand people showed up to share stories. Bands that Wild Bill loved played out in the fields. However, some of his plans and projects have had to be put on hold while legal and logistical questions are answered. “The general sense is ‘Let’s keep this place going,’” says Joe. “But the logistics are, you know … no one could do it like Bill could.”

An older couple, a man and a woman, come into the store, and the man asks about the record collection. The woman tells Heather that she remembers this place from even before Wild Bill moved in. (It belonged to the Knights of Columbus and, before that, was a night club where Heather’s grandfather once played the harmonica.) “I heard that you were planning on closing the store down,” she says.

“No, we’re not closing it down,” Heather tells her. And then, more quietly, “Not yet. Hopefully not at all.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook