Remembering the World War II Frogmen Who Trained in Secret off the California Coast

Recruits learned the arts of infiltration, sabotage, and survival at a hidden base on Santa Catalina Island.

Dick Hamada plunged from a boat into the pitch-black Pacific and swam toward the island of Santa Catalina, a dark shape against the night sky. It was the autumn of 1944, and the 22-year-old was a member of America’s first intelligence agency, the Office of Strategic Services (OSS).

Hamada and fellow recruits had been assigned to sneak past soldiers guarding the beach and infiltrate a building on the point. It was just an exercise, but the soldiers stationed on shore, carrying live rounds in their rifles, didn’t know that. “Had [the OSS commandos] been sighted, they would have been seen as infiltrating spies,” says Johnny Sampson, chief curator of the Catalina Museum for Art and History.

The guards were on high alert over fears that Catalina, less than 50 miles from Los Angeles, might be used as a staging ground for a Japanese invasion of the mainland. Hamada and his class of 13 other Japanese American commandos were particularly vulnerable to friendly fire: As fellow recruit Ralph Yempuku would later tell historian William Sanford White in the book Santa Catalina Goes to War, they “looked like the enemy.”

Glancing up from the dark ocean, Hamada spotted soldiers walking back and forth on a pier. He thought, “I can see him, but he can’t see me,” he’d recall in an oral history for The Hawai’i Nisei Project. After each such training mission on Catalina during this period, the only trace of the commandos was an “X” scribbled on the post office, bank, and other targets.

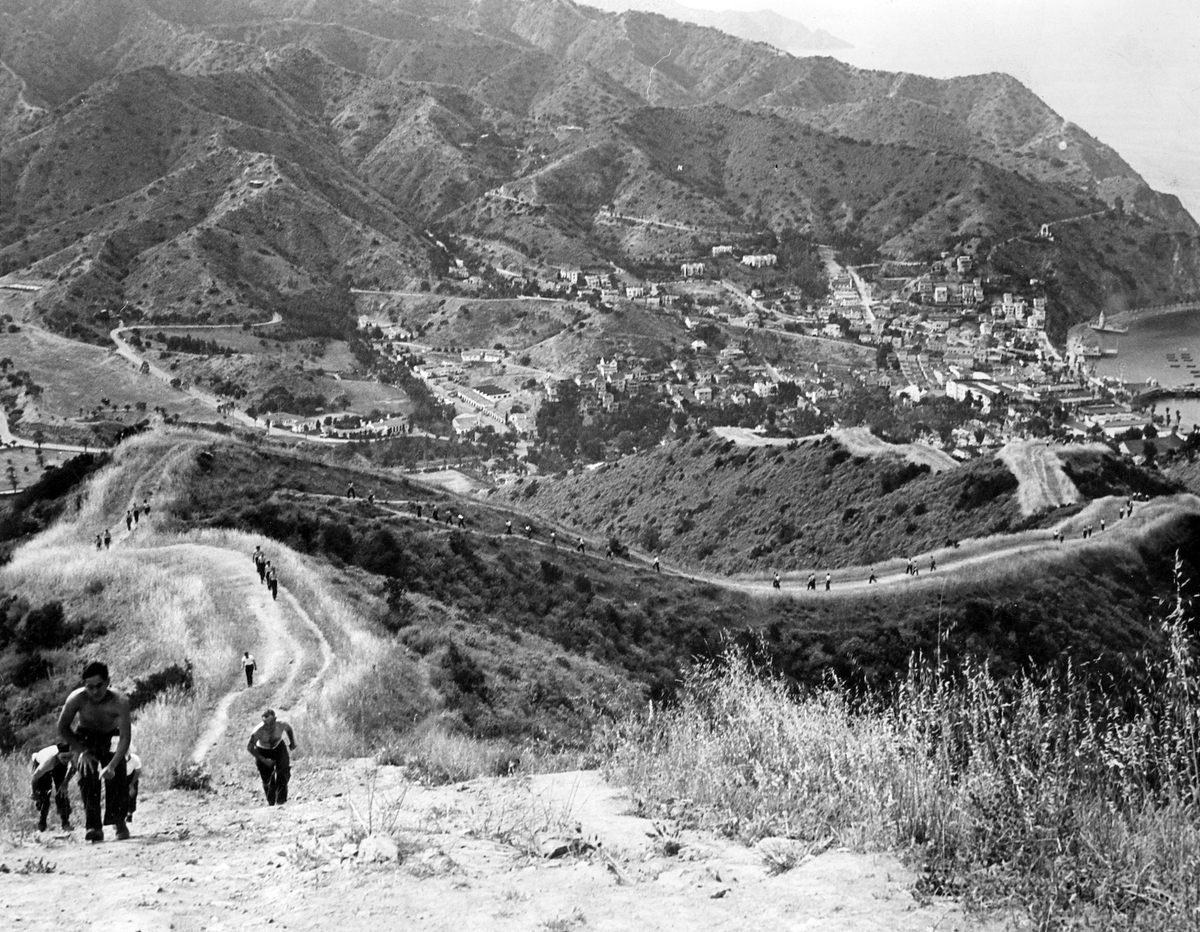

A forerunner to the CIA, the OSS was created in June 1942 to conduct espionage activities behind enemy lines. Training was conducted at 16 bases nationwide, with the Catalina facility specializing in maritime raids and infiltration. Part of the Channel Islands archipelago, Catalina stretches about 22 miles in length, with a shoreline of sandy coves and rocky beaches, and mountains as high as 2,000 feet.

The OSS established its main base at Toyon Bay, a sheltered inlet two miles from the island’s main town of Avalon. Toyon Bay was home to a former boarding school, which the OSS converted into barracks, a mess hall, administration offices, and classrooms. The rugged terrain surrounding the cove was perfect for testing the recruits’ physical endurance, and resembled the geography the men would find in East Asia. Most importantly, Toyon Bay was secluded, surrounded by steep cliffs, with no road in or out of the area at the time. The Catalina OSS base was kept top secret during World War II; not even local residents and other service members stationed on the island were aware of its existence. Only in the 1980s, according to Sampson, were OSS files about the base declassified.

The commandos who trained on Catalina Island were primarily attached to the OSS’s Maritime Unit, assigned to insert into enemy territory by sea for reconnaissance and sabotage. To fill its ranks, the agency recruited top swimmers from throughout the armed forces. Korean prisoners of war, released after showing a commitment to fighting the Japanese, also participated in OSS training on Catalina.

Recruits with Japanese ancestry, such as Hamada and Yempuku, were invaluable as linguists and translators, and for their ability to infiltrate Japanese-controlled territory. Hamada grew up in Hawaii where, on December 7, 1941, he’d aimed a telescope at the sky and witnessed swarms of Japanese aircraft attacking Pearl Harbor. Even as Japanese Americans like him were being locked in internment camps by the U.S. government, he’d volunteered to serve his country as a member of the OSS—despite rumors that commandos had a 10 percent chance of survival.

To improve those odds, the recruits drilled in hand-to-hand combat, cryptography, map reading, and radio operations. For conditioning, they did calisthenics on the beach and took long runs up Catalina’s peaks and along its ridges. They also participated in multi-day survival exercises. Equipped with just a knife and a length of fishing line, the men built primitive shelters in the mountainous interior and hunted the island’s wild boar and feral goats. (Catalina also had a large bison herd, which had been brought to the island for a Hollywood film shoot in 1924. There is, however, no record of an OSS man ever bagging a bison.) Yempuku, another native of Hawaii, had trapped animals as a boy and proved adept as a survivalist, even catching the fast-moving quail that skitter through Catalina’s chaparral. Hamada was less enthusiastic, particularly when his team had to skin and gut a goat. “That was kind of nauseating,” he said. He preferred using a grenade to detonate his dinner, recalling: “You drop a hand grenade in the ocean and you’d see all kinds of fish…crab, abalone.”

The recruits spent many of their waking hours in the ocean, practicing swimming ashore in stealth, attaching dummy limpet mines to ship hulls, diving underneath flaming pools of oil, or blowing up replicas of enemy obstacles. They also tested state-of-the-art equipment such as mini-submersibles, collapsible kayaks, and water-resistant weapons and ordnance, and were among the first to use primitive SCUBA equipment in the ocean.

Jon Council, who heads the Historical Diving Society’s American chapter and operates a diving museum in Avalon, says the trainees “didn’t invent the equipment, but they certainly pushed forward the minimization of its overall size.” Divers had previously used heavy helmets and suits connected by hoses to surface oxygen pumps; the OSS commandos pioneered lightweight and compact rebreathers, such as the Lambertsen Amphibious Respiratory Unit (LARU) and Desco B-Lung. The devices made it easier to maneuver underwater and emitted no bubbles, increasing stealth.

After their training on Catalina, most of the OSS commandos deployed to the Central Pacific and East Asia, where they served with distinction as saboteurs and guerilla fighters. The OSS was disbanded by President Truman at the end of the war but the Maritime Unit’s legacy lives on. Its underwater demolition techniques, swim reconnaissance training, and other trailblazing methods were “the beginning vestiges of what would become the Navy SEALs,” says Council.

Today, Toyon Bay is the site of a children’s science camp. Students study and sleep in the same buildings once used by the OSS; further up the valley, a tennis court has replaced the old firing range. There is currently no memorial to the commandos on Catalina, although you occasionally encounter traces of them. Spent shells can be found glistening in the waters just off Avalon; a little further out, divers might notice a heap of collapsed metal on the ocean floor, the remains of an underwater obstacle course intended to prepare commandos for navigating in and out of enemy harbors. It’s a last relic of Catalina’s secret OSS base, but it’s nothing much to look at, says Council. “If you didn’t know what it was, you’d just think it was old rusty junk sitting on the bottom.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook