Where Are the World’s Most Dangerous Seas?

From the Drake Passage to the Bermuda Triangle, these waters have a reputation for death and destruction.

In December 2004, San Francisco business owner John Dorning embarked on his first journey aboard the iconic Queen Elizabeth 2. Dorning was making the crossing from Southampton, England, to New York City. It was their first full day at sea. “Sometime during the afternoon, the weather suddenly started getting really rough,” says Dorning.

Within minutes, gale-force winds were whipping through the air. They created massive waves, causing the bow of the ship to pitch upward and then slam back down. A series of loud booms accompanied each pounding, the sounds almost deafening. The entire ship was shuddering and vibrating. Dorning, who spent his teenage years working on clamming boats off the coast of Long Island, rarely got seasick. This was an exception.

“First, my stomach started feeling queasy,” he says. “Then I noticed this little layer of cold sweat on my face.” About the same time, Dorning became aware of the ship’s barf bags, discreetly placed beside the elevators and stairways. “Once I started looking, I saw them everywhere,” he says.

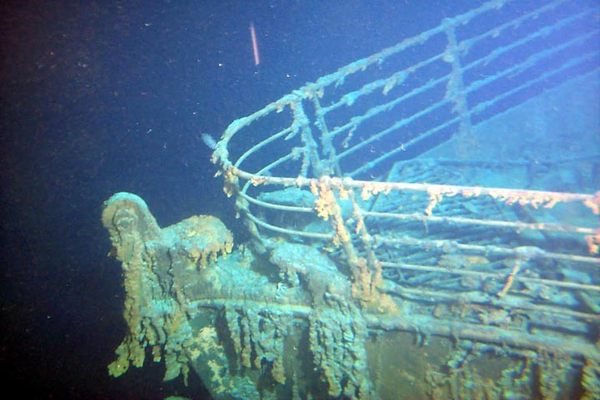

The Atlantic Ocean between Southampton and New York City is a notoriously rough stretch of sea, especially during winter months, when heavy winds and rains can seemingly whip up in an instant. But despite this being the final resting place for the RMS Titanic—which sank in 1912 about 400 miles off the coast of Newfoundland—most marine professionals wouldn’t deem it to be the world’s most dangerous body of water. More likely candidates would be the infamous Drake Passage, a deep waterway that lies between South America and the Antarctic Peninsula, the seas around South Africa’s Cape of Good Hope, and those off Cape Horn—the southernmost headland of South America’s Tierra del Fuego archipelago. But when it comes to nailing down which of the world’s seas are the most dangerous, the answer gets complicated quickly.

“Factors like weather, water depth, and currents are all a part of defining rough or dangerous seas,” says Lindblad Expeditions’ Heidi Norling. As captain of the company’s National Geographic Resolution, a Polar Class 5 ship built for extreme high-latitude conditions, Norling has seen her fair share of maritime challenges. These include the ice-laden waters around Antarctica and in the Arctic. There, says Norling, a combination of unusual conditions—such as low pressure systems with high seas and strong winds, which can cause a ship to roll or pitch up and down—can really wreak havoc on ships.

Ocean crossings are also well known for rough seas, like those Dorning experienced, because there are no large landmasses to slow or redirect winds and currents. “I’d say the North Atlantic is the roughest of the northern oceans, for sure,” says James Griffiths, general manager of ocean operations for Scenic Cruise Services and a captain with more than 20 years of at-sea experience. “Those very strong prevailing westerly winds, paired with low pressure systems that often start in the Caribbean, move up and curve over the North Atlantic Drift, staying very strong over a prolonged period of time,” he says.

In addition, dangerous waters exist where the current moves in one direction and the wind blows in another. This can give rise to so-called freak or rogue waves, terrifyingly large waves up to 100 feet high. “They are quite unusual,” says Griffiths. “But they do happen.”

One such place is the waters around the Cape of Good Hope, a rocky promontory at the southern tip of the African continent. It’s where the Atlantic and the Indian oceans meet. Here, the warm waters of the fast-flowing Agulhas current, moving east from the South Indian Ocean, and the cold and wide Benguela current, traveling west, create the perfect storm for these unpredictable ocean monstrosities to occur.

Winter weather brings its own set of issues to already precarious seas. It might be exceptionally strong winds caused by a greater pressure difference between air masses, or freezing sea ice that makes navigating waters nearly impossible—conditions that have challenged mariners throughout history.

The Age of Exploration (1492-1607) is especially full of tales regarding sunken ships and stranded sailors, particularly in the most notorious waters, such as around Cape Horn. English explorer Sir Francis Drake (for whom the Drake Passage is named) found himself navigating this place of fierce winds and massive waves, where ships had to contend with stray icebergs, rocky coastal shoals, and the Southern Ocean’s circular current, which flows unimpeded by land. Before the opening of the Panama Canal in 1914, sailing around the Horn was the primary maritime route between New York and North America’s west coast. It was a costly one, too. At least 100 sailing vessels were lost around Cape Horn between 1850 and 1900, including some carrying prospectors and supplies to the California Gold Rush.

Then there’s Drake Passage, which stretches approximately 600 miles just south of Cape Horn. “When you get further and further in latitude toward the poles, you get higher winds and in turn, higher waves,” says Daniel Wagner, chief scientist at Ocean Exploration Trust, a nonprofit dedicated to ocean exploration. “You also get more unpredictable kinds of patterns. In turn you get a lot of shipwrecks.” The Drake Passage has seen more than 800 of them, claiming the lives of some 20,000 sailors.

For anyone considering travel to Antarctica, crossing the Drake Passage is often the biggest obstacle standing in their way. Norling believes that this body of water is worthy of its fear-inducing reputation, due to its potential for 30-foot-plus waves and gale-force winds. The area’s waters are so unpredictable that passage through them is often referred to as the Drake Shake or—during unexpected periods of eerie calm—the Drake Lake.

One of the world’s most notorious stretches of water is the Bermuda Triangle, a 500,000-square-mile area of the Atlantic between Bermuda, Puerto Rico, and Florida’s southern tip. At least 50 ships are believed to have vanished here, leading to some wild speculation. The truth is more mundane: Many Atlantic hurricanes and other severe storms travel through the loosely defined triangle, which is also heavily trafficked by vessels of all sizes. More storms and more ships mean more wrecks. There is also some research that suggests the region is home to localized magnetic anomalies—a phenomenon found in several places around the world—that could cause errors in older navigation methods. It’s no coincidence that the number of vessels reported as lost fell as both weather prediction and navigational tools improved. But while most mariners agree that the Triangle is safe, its legendary status lives on.

According to veteran mariner Griffiths, the reputations of the North Atlantic, Drake Passage, and many other notorious waters are all well deserved. However, the safety of traveling through them has improved dramatically. For instance, purpose-built vessels plying Antarctic routes have features such as strengthened hulls and oversized stabilizers that help steady the ships in high winds and battering waves.

Advances in weather forecasting and satellite navigation systems have also changed how sailors view the world’s roughest seas. “These days you don’t often run into weather that hasn’t been forecasted,” says Griffiths. Well ahead of extreme conditions, crews also complete severe weather checklists to prepare vessels, including closing watertight doors, securing open decks, and prepping the engines to handle any required major changes to course or speed.

Despite all the modern technology and safeguards, rough seas can’t be avoided completely. And some people actually seek them out, such as members of the Cunard Winter Crossing Club, many of whom are repeat passengers on the line’s mid-December transatlantic voyage, which often encounters wild weather.

“They’re like storm chasers, but with martinis in hand,” says Dorning, who was not dissuaded by his initial transatlantic crossing. Since that 2004 experience, he’s done it nine more times, and confirms the Atlantic has earned its “not for the faint of heart” reputation.

Regardless of the reputation of any particular body of water, veteran mariners know the most dangerous stretch of sea is the one you underestimate.

As Norling, an experienced captain, puts it: “Even in a beautiful location where things appear calm, anything can happen on a dime.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook