The World’s Shortest War Ended Less Than an Hour After It Started

But it’s not easy to say how long the Anglo-Zanzibar War actually was.

Sayyid Khalid bin Barghash Al-Busaid got to be sultan for a day. A little more than that, actually—42 hours—give or take 10 crucial minutes.

It was August 1896 in Zanzibar, the island off the East African coast that is now part of Tanzania, and Khalid’s cousin, Sultan Hamad, had died suddenly. Rumors spread that he had been poisoned, and Khalid was under a cloud of suspicion. In Zanzibar, according to Geoffrey Owens, an anthropologist at Wright State University, “There was a long history of brothers and uncles and cousins trying to overthrow one another.” But the young prince was likely more concerned with the British Empire, which was threatening to declare war on him.

The Anglo-Zanzibar War, as the ensuing conflict is known, was composed of a single battle between an empire upon which the sun never set and an island nation half the size of Rhode Island. It has gone down in history as one of the most lopsided conflicts in history, and certainly the shortest. But due to the murky matters of the rules of engagement, inconsistent reporting, and an extreme lack of clocks on the scene, it’s impossible to say how long the “shortest war” truly lasted.

At the time, Zanzibar was technically its own country, though the British had established a protectorate in the region. The colonial power had coveted the island for its clove industry, which was the largest in the world at the time. Zanzibar’s governing structure was “dual jurisdiction,” in which the British legal structure functioned alongside the Zanzibari sultanate, itself a product of the island’s previous colonization by Omani Arabs earlier in the 19th century.

“The British, at that point, they want a lapdog,” says Elisabeth McMahon, a historian at Tulane University who specializes in East Africa. “They want someone wholly in their pocket.”

Khalid was not that person. The British had been seeking to end slavery in Zanzibar, an agenda that Khalid’s father, when he was sultan, had notoriously resisted. Hamad had been more cooperative toward British interests, but Khalid was openly defiant of their authority. He had attempted to take the throne before, so when he abruptly announced himself sultan after Hamad’s death, the British went into crisis mode. They were supposed to have approval over who became sultan. Consul Basil Cave and the portly First Minister Lloyd William Mathews rallied their naval power. Cave warned Khalid his declaration of sovereignty constituted an act of rebellion. Things escalated quickly.

“Are we authorised in the event of all attempts at a peaceful solution proving useless,” Cave wrote to British Prime Minister Lord Salisbury, “to fire on the Palace from the men-of-war?”

Salisbury assured Cave that he had the crown’s support. Khalid, ever-defiant, quickly overplayed his hand. A messenger from the Zanzibari palace declared to the Brits, “We have no intention of hauling down our flag and we do not believe you would open fire on us.” Whoops. In a curtly British reply, Cave responded, “We do not want to open fire, but unless you do as you are told we shall certainly do so.” What happened next was—technically, at least—a war.

Asked about the definition of war, Michael Rainsborough, head of the Department of War Studies at King’s College London, turns to the writings of Prussian general and war theorist Carl von Clausewitz. In his treatise Vom Kriege (On War), von Clausewitz defined it as “an act of violence intended to fulfill our will.” His other, perhaps more popular maxim, is that “war is the continuation of politics by any other means.” Wars can constitute many kinds of conflicts—insurrections, proxy wars, revolutions, civil wars, and more—and their beginnings and ends can be obscure. They can begin without declaration, and can end without surrender.

“It is not defined by duration or extent, or bound by formal declarations of the beginning and the ending of hostilities,” says Rainsborough via email. “War can be an instantaneous discharge of violence or a conflict extending over years, decades, or centuries.” The events in Zanzibar were much more like the former.

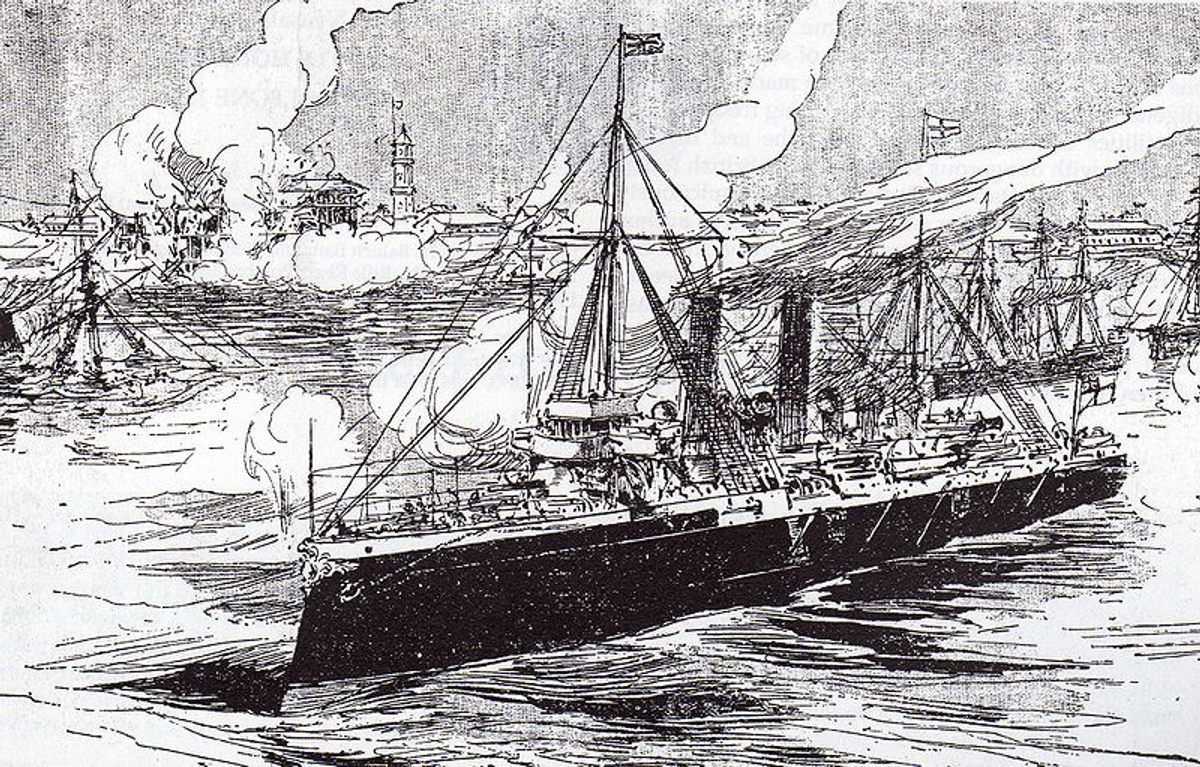

At 9:00 am, on August 27, having received no reply from the palace, the British ships amassed in the harbor and instantaneous discharged violence on Khalid. The outcome was never in doubt.

“The town of Zanzibar is right on the water, and the sultan’s palace in town is directly on the waterfront,” says McMahon. “When Khalid locks himself in the palace, it’s easy for the British to take their boats right there and just shoot into the palace.”

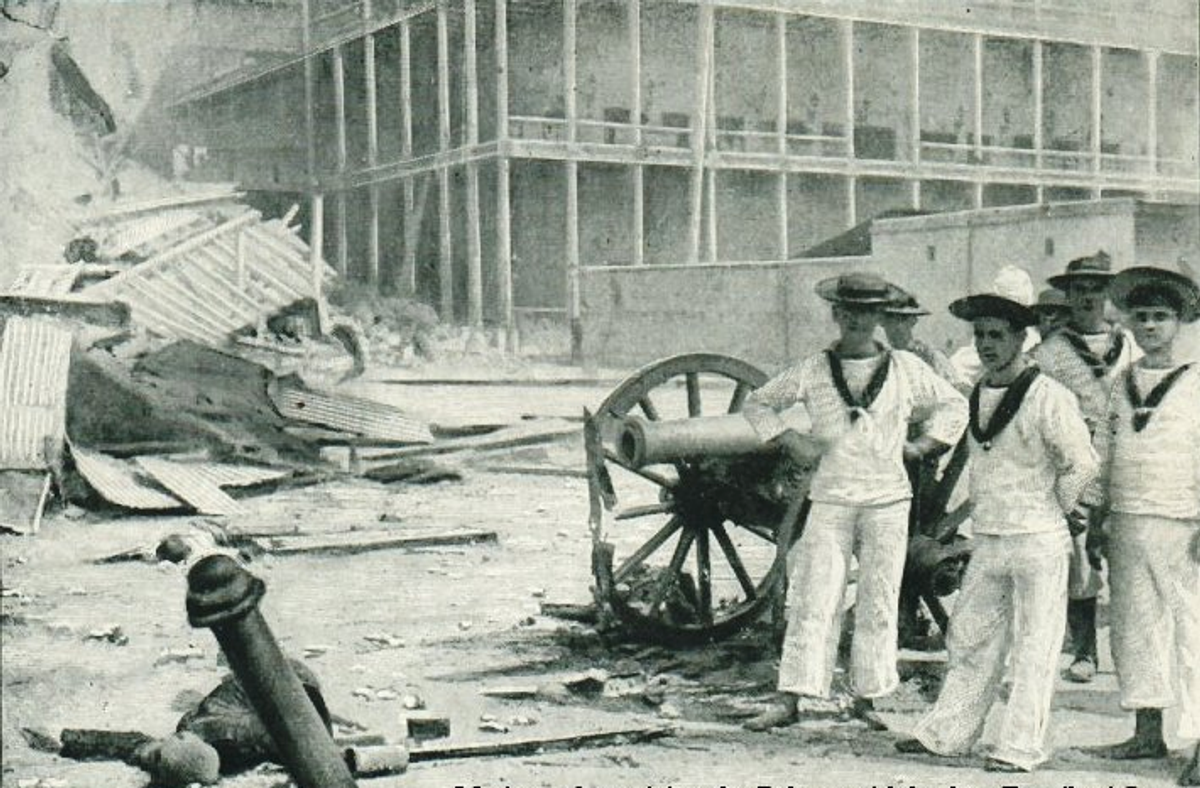

The royal yacht was sunk almost immediately and settled to the harbor floor, its masts jutting out of the water like periscopes. Mortar and stone from the palace lifted in the air and tumbled back to the ground, disassembled.

In a matter of minutes, about 500 Zanzibari soldiers and civilians were killed or wounded. Just one British seaman was injured. How many minutes it lasted, however, is uncertain. A New York Times report the following day said 50; two months later, the same paper said 30. The Guinness Book of World Records says 45. Nobody really knows. (The next shortest wars—such as the 1969 “Football War” between El Salvador and Honduras, and the Six-Day War of 1967—lasted at least the better part of a week.)

The British shelling was definitely less than an hour, but war chroniclers didn’t keep track of every shot fired that day. It’s impossible to say its exact duration in the absence of anything official or definitive. Scholars generally cite the war as having lasted between 38 and 45 minutes. Any additional specificity would be a matter of guesswork.

“They bombed the clocktower, so the big indicator of time in town wasn’t available,” says McMahon. “Most people in town didn’t have watches, so that seven-minute difference in time is hard to say.”

The smoke lifted and dust drifted, and Khalid had fled, seeking refuge in the German consulate down the coast. Military historian Hew Strachan, of Oxford University, notes that “an individual cannot go to war. It is a group activity.” Despite this, the British spent the rest of the day tracking the prince down—maybe further challenging the length of the war itself.

“The reality is they bombed, and he fled, and this ‘shortest war in history’ thing probably took the whole day,” says McMahon. “It still may be the shortest war in history, but it was probably a day-long thing.”

The Germans did not turn Khalid over, but assured Britain that the offending prince would never touch British (and hence Zanzibari, at the time) soil again. Khalid was spirited away to Dar es Salaam, then part of German East Africa. He would eventually set foot on British soil, as following a spell in exile, he died in British Mombasa in 1927. The propped-up sultanate—under more compliant “rulers”—continued until the island gained independence in the 1960s, followed by a merger that created modern Tanzania.

For all its brevity and imbalance, the Anglo-Zanzibar War could go by other names—rebellion, insurgency, massacre—all of which it was. These categories of conflict, it turns out, overlap. This asymmetric war was also a colonial war, as it was an uprising, as it was an attempted coup. Whatever you call it, it was brief.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook