Why Do So Many U.S. Towns Have the Same WWI Soldier Statue?

Decoding the Doughboy, one of the first mass-produced memorials.

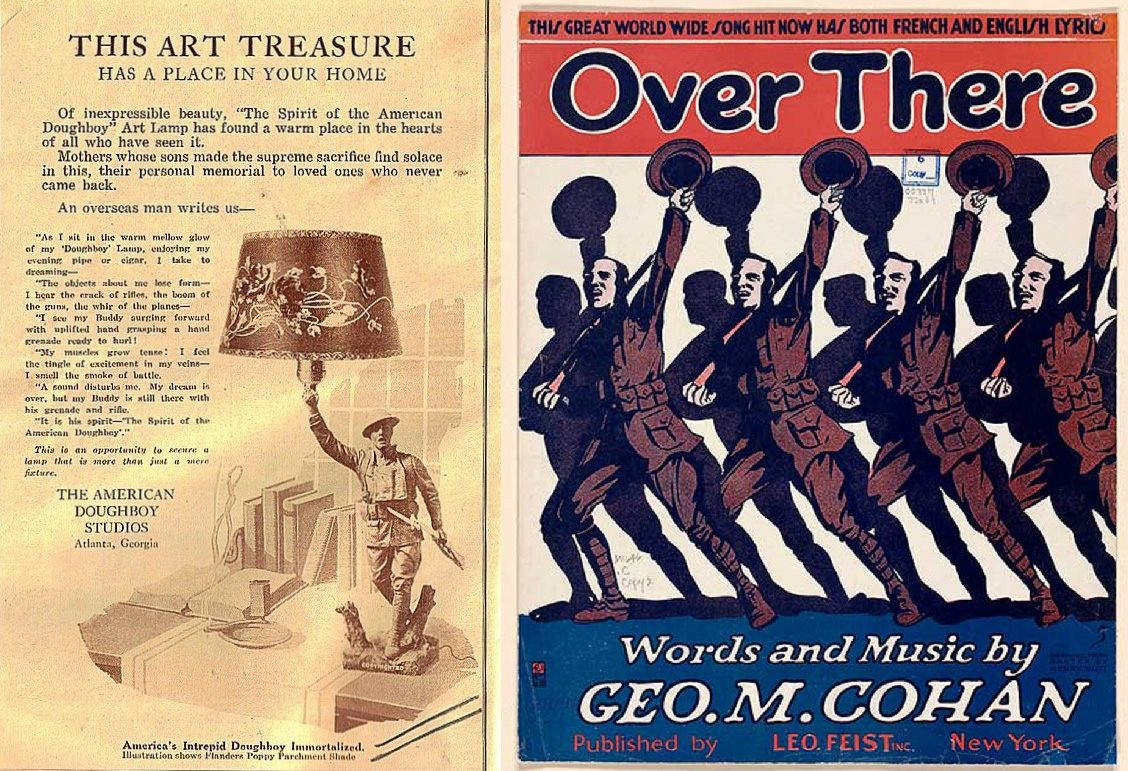

E.M. Viquesney’s the Spirit of the American Doughboy memorial features a single man, dressed in a World War I army uniform, complete with a hat. He raises his right fist, which holds a grenade, toward the sky triumphantly, proclaiming victory. His other arm holds a rifle, complete with a bayonet. And he is everywhere, from Alabama to Wyoming.

These doughboy memorials, all featuring the statue and a stone or brick base, can be found in 39 U.S. states. They sit in town squares, in cemeteries, in front of federal buildings, and in parks. There are around 145 of them, and they all look very familiar—for a good reason. These statues are among the first known mass-produced memorials in existence.

Prior to World War I, if someone wanted to erect a memorial, a complicated process had to be followed. That person had to not only get permission from city hall (or the owner of the piece of property where the memorial would be placed), they also had to put together a memorial committee, raise money, hire an artist, and go through all of the steps required to create one from scratch. This was not cheap, especially once you considered the cost of the stone, usually marble, that went into the memorial sculpture. Viquesney changed all of that.

Born Ernest Moore Viquesney, the Indiana native served in the Spanish American War. He also grew up wanting to be an artist, although he was warned by his father that he would die poor, as “art” wasn’t a real career. However, Viquesney proved him wrong. He started working for a memorial company in Americus, Georgia, where he created the marble headstones for the U.S. Civil War soldiers buried in Andersonville National Cemetery. Though the headstones brought him recognition, Viquesney’s real claim to fame occurred years later, after the end of World War I, when he realized that people would want to memorialize the war in some way.

Viquesney wasted no time in starting his doughboy sculpture, beginning work on it immediately after the war ended in 1918. He had several returning soldiers pose for him while wearing their full combat gear. While he could have had them stand simply, with both arms down, Viquesney wanted a triumphant pose to be the legacy of the war. He chose a position that mimics that of the Statue of Liberty, an important American icon.

By 1920, two years after the war ended, Viquesney applied for a patent for his design, because he planned to mass market it, thus making the memorial statue more affordable and easier to set up all across the nation. His ingenious idea? Instead of carving each doughboy out of marble on demand, he created a mold for them. When one was ordered—at a reasonable rate of $1,500 (around $20,000 today, as opposed to the tens of thousands in 1920s dollars that a personalized memorial cost) Viquesney simply ran one in either pressed copper or cast zinc and then coated it in bronze. They were lighter than marble, thus easier to ship, and the molding process took much less time than sculpting each by hand. He also created smaller versions of the sculpture, as well as one that served as a lamp base, making it possible for veterans or others to place a doughboy in their homes. So much for not making any money as an artist.

Viquesney placed ads in newspapers and magazines around the country for his Spirit of the American Doughboy. In them, he claimed to have sold 300 of the full, 7-foot-tall memorial sculptures, and that there was at least one in every state (48 at the time.) While these claims haven’t been substantiated, the doughboy iconography was so popular that plenty of small towns snapped them up. He produced the statues through a partnership with foundry Friedley-Voshardt Company up through 1934. The popularity of them soared. And then Viquesney’s competitors got involved.

One such competitor, John Paulding, actually patented his Over the Top doughboy sculpture six months before Viquesney. Paulding’s soldier looks a lot like Spirit of the American Doughboy, down to the uniform and triumphant fist. Paulding also came up with different models, each a slight variation on the others. For example, a different knee would be bent, or the gun would be held at another angle. His statues were in cast bronze without the metal underlay of Viquesney’s, making them slightly more expensive. Only 34 of Pauling’s memorials still exist today.

There are other lookalikes, produced in smaller numbers, scattered throughout the country. Some have very similar poses, but are made from different materials, including marble (although Viquesney did make three from marble himself; they are all located in Georgia), and granite. However, none of them had the spread and popularity of Viquesney’s doughboys, which helped people remember the soldiers that fought and died in World War I—the Great War of its time, soon to be overshadowed by its sequel.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook