Uncovering the Forgotten Female Astronomers of Yerkes Observatory

It all started with a photo of Einstein.

The quest started with a single, black-and-white photograph.

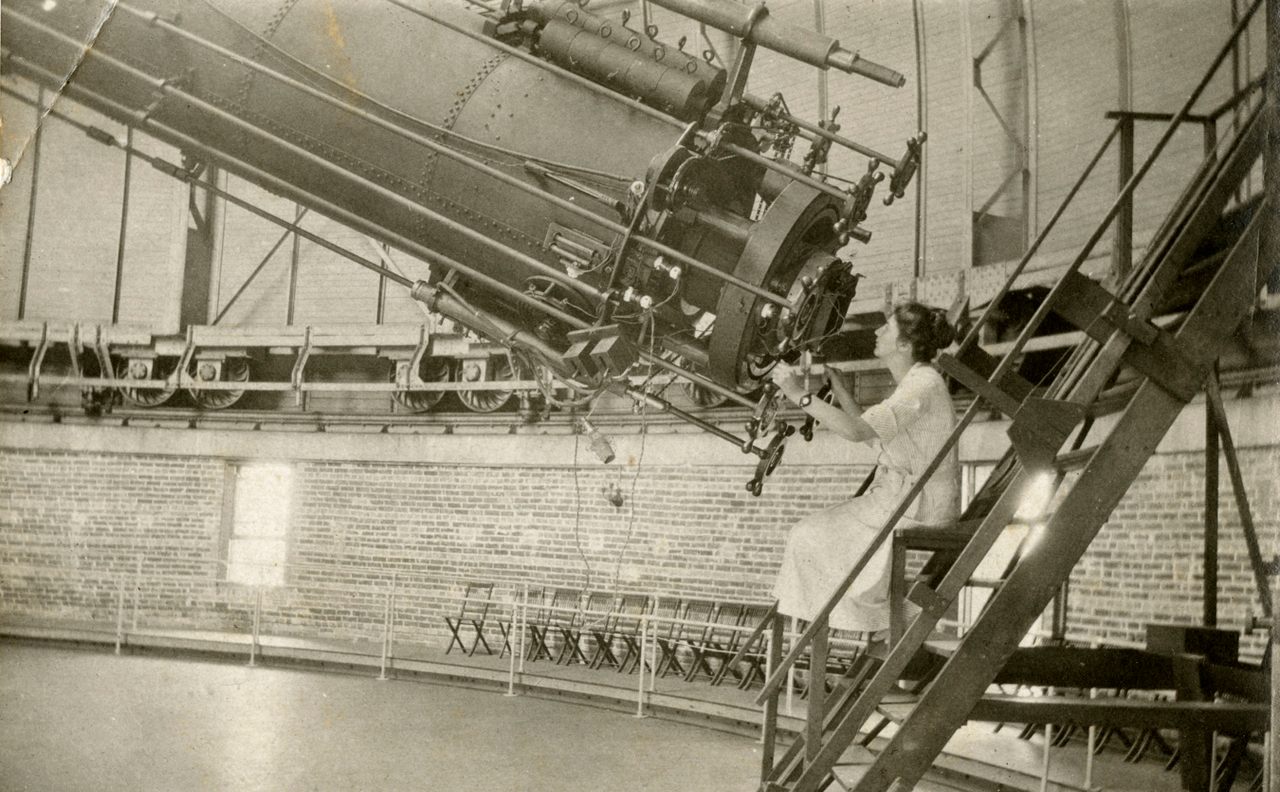

A massive telescope dominates the frame. In May 1921, when the image was captured, the 54-foot-long, 1,200-pound refracting telescope at the University of Chicago’s Lake Geneva Yerkes Observatory was the largest of its type in the world, capable of revealing unseen corners of the universe. Beneath this behemoth is a crowd of scientists. One, with a shock of wild gray hair, stands out.

Nearly a century later, a group of researchers at the University of Chicago evaluating the photograph (below) recognized that distinctive coif first: It was, unmistakably, Albert Einstein, on a whirlwind tour of the United States in the early days of his global fame. Some of those gathered around the physicist were also well-known to the researchers. The distracted-looking man with his tie askew was Edwin B. Frost, the then-director of the observatory. The white-haired man with the walrus mustache was Edward E. Barnard, an astronomer known for his photographs of the Milky Way. “And then someone in the room asked a deceptively simple question,” recalls Andrea Twiss-Brooks of the University of Chicago Library. “Who are all the women in the photograph?”

Of the 19 people documented alongside Einstein that day eight were women. They stand shoulder to shoulder with the men in this hallowed space of scientific exploration, an unusual sight in the 1920s. Even more surprisingly, while their presence at the observatory has been forgotten in the intervening decades, they were not overlooked in 1921. In the margin of another copy of the photograph in the University of Chicago archives, someone identified each person by last name. “Once we had names,” says Twiss-Brooks, “being a librarian, I knew what to do.”

Over the last three years, Twiss-Brooks and her team—including historian Kristine Palmieri and a group of undergraduate students—have rediscovered the lives of many of these women and the story of this unique place in Williams Bay, Wisconsin. In the first half of the 20th century, when men dominated the world of scientific research, Yerkes Observatory employed more than 100 women, some as secretaries; some as “computers,” solving mathematical equations; and many as astronomers. At Yerkes, women scientists could reach for the stars.

Dorothy Block is one of the women in the photo with Einstein. In the spring of 1921, she was 30 years old and a doctoral student with the title of assistant of stellar spectroscopy at Yerkes, a role which required her to operate the impressive refracting telescope. Block was already a graduate of Hunter College and Columbia University and had served as a fellow at the Harvard College Observatory, but still, when she applied to Yerkes in 1919, Edwin Frost was obliged to inform Block that she would be a welcome addition to the observatory—if the two men who had also applied for the position declined it. (They did.) A male professor at Harvard was enthusiastic about her appointment, writing to Frost, “I think Miss Block would do very well anything she undertakes… She has just the right personality, and her astron[omical] Work is done for love of it, for she could get more pay teaching.”

Kristine Palmieri, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Chicago’s Institute on the Formation of Knowledge, found Block’s story told in bits and pieces in government records, newspapers, astronomical publications, and correspondence and journals archived at Harvard University and the University of Chicago, where Yerkes’ extensive records are held. (The Yerkes Observatory is no longer affiliated with the university.) Among the items preserved in the Yerkes collection is another, more personal image of Block: It’s a photo of her engagement party.

For Palmieri, the image helps to explain why the hard-working and well-respected scientist never got the degree she had come to the observatory to pursue—most women of the era gave up their careers upon marriage. But it also provides insight into life at Yerkes: Block married fellow astronomer John S. Paraskevopoulos, who was doing post-doctoral work at the observatory, and many of the same colleagues who stare out, somber-faced from that photo with Einstein can be seen rejoicing with the couple. (Block would continue to work, mostly in an unofficial capacity, alongside her husband throughout his career.)

“One of the really exciting things about Yerkes is that we’ve really been able to demonstrate that there wasn’t some sort of gendered division of labor that we see in other places,” Palmieri says. At other observatories, like the one at Harvard where Block had worked, the women were physically segregated from the men. At Yerkes, men and women could hold the same jobs, in the same place.

“Was it something about the place?” Twiss-Brooks says. “Was it something about the environment that the director fostered there? We think the answers are ‘yes.’” From its founding in the 1890s, the University of Chicago accepted women on an equal basis with men, an ethos that seems to have extended to the observatory. Yerkes was also accessible to the town of Williams Bay and the city of Chicago, providing more socially acceptable options for transportation and housing for young women than could be found at remote mountain-top astronomy outposts. And then there was Edwin Frost, the director of the observatory from 1905 to 1932.

Twiss-Brooks and Palmieri hypothesized that Frost, whose letters to women scientists were supportive and encouraging, was key to the progressive hiring practices at Yerkes. Finally, in one of those “kind of gifts you always hope for” in the archive, Palmieri found a letter Frost penned to Caroline Furness, an astronomer at Vassar College, in 1916.

“You probably know that we are running the Observatory this year by woman power, all the men here being ‘old’ married men,” he wrote. He lists the women scientists, from Swarthmore, Smith, Mt. Holyoke, and Vassar, and adds, “The work of the institution goes on as usual, which should be a matter of congratulations to all suffragists—like myself.”

In the fall of 2023, the University of Chicago Library mounted an exhibit about the women of Yerkes, a peek into life at the observatory which included both scientific and personal artifacts. There is a photo of the staff in their bathing costumes at a picnic and a watercolor of Yerkes painted by Marguerite van Briesbroeck, who worked as a librarian there, but the research into the lives of the women astronomers who passed through this unusual place continues.

There’s an important story to be told about what is recognized as scientific work, who is given the support to pursue their own research, and which contributions are remembered, says Palmieri. Those are all questions the scientific community continues to grapple with today.

Take, for example, a letter from a woman working at the Naval Observatory in Washington DC in 1922. Isabel Lewis wrote to thank Edwin Frost for his feedback on her manuscript, Astronomy for Young Folks. But, she admitted, “the book is not what I wanted it to be…I simply can’t get the time to write.” She was working as a part-time computer and supplementing her income as a scientific writer. She was determined to read all the necessary bulletin and periodicals, and “then too there is a lively boy of eight who demands a good share of my time and a house to take care of in addition.”

“I know so many of my colleagues who are women who could basically write that now,” Palmieri says.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook