Your Ticket to the 1893 Columbian Exposition

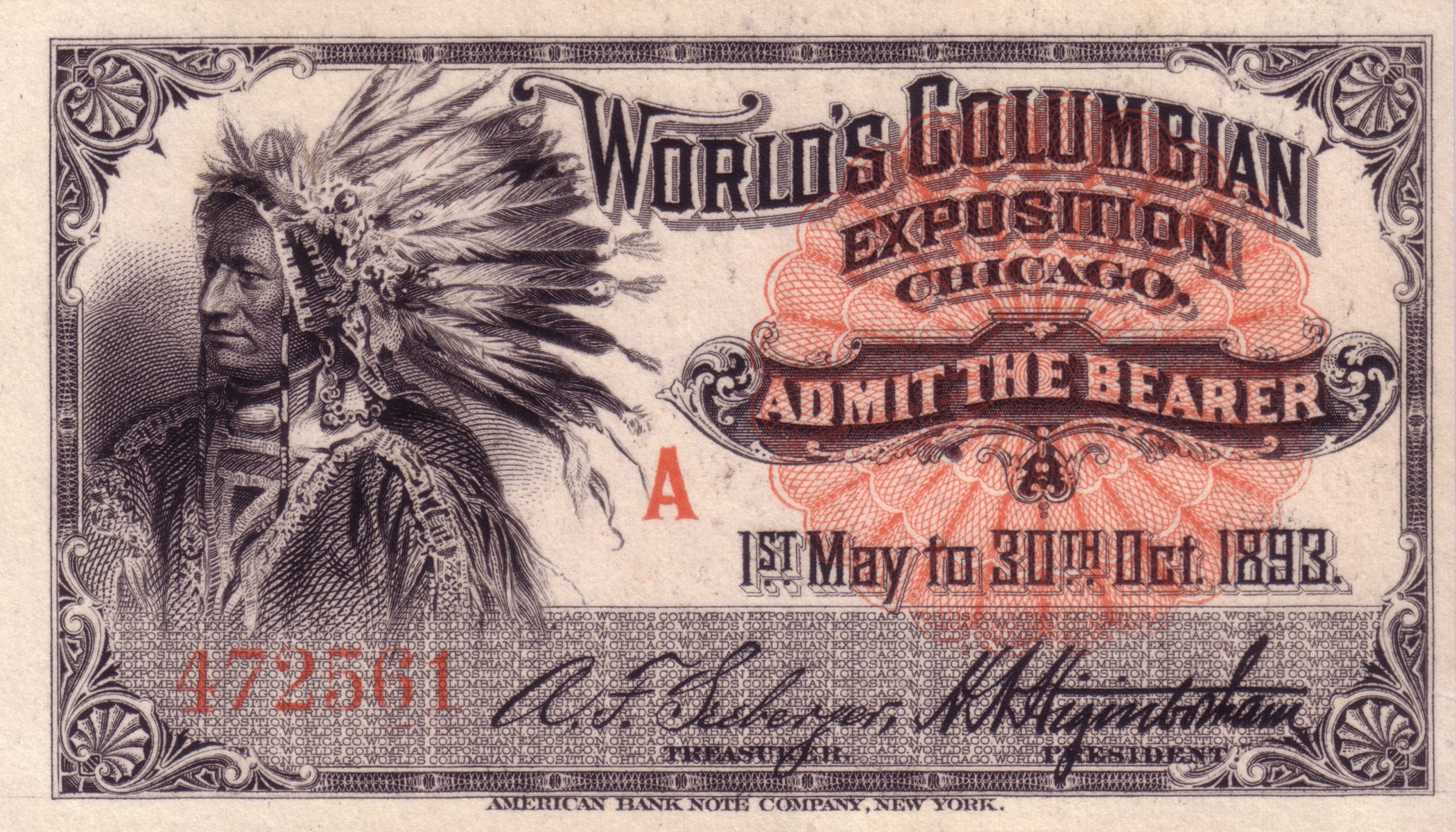

This ticket to the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition showed a Native American chief. Actual American Indians were “displayed to fairgoers as objects of anthropological inquiry.” [All photos: Tom Hoffman]

This story was sponsored by the fine folks of Enjoy Illinois.

Chicago fought hard to host the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition. The competition was steep—New York and D.C. were also top contenders—and the city was still recovering from the Great Chicago Fire two decades earlier. But after they won the bid, city organizers pulled out all the stops. The “White City” they built on six hundred acres of filled-in swamp ran for six months and drew people from 46 countries. Overall, 27 million people came through its turnstiles and ticket booths to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus landing on American shores.

After it was over—when the temporary buildings began to come down, the sounds of the demonstrations died away, and the birds picked at the concession crumbs—fairgoers just had a few tokens to remember it by. Luckily, they were very well-designed tokens, taking the symmetrical, grandiose aesthetic of the entire fair and shrinking it down to pocket size. Below, a collection of 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition souvenirs that might have ended up in your memory box, had you been a 19th-century fairgoer.

Portrait Tickets

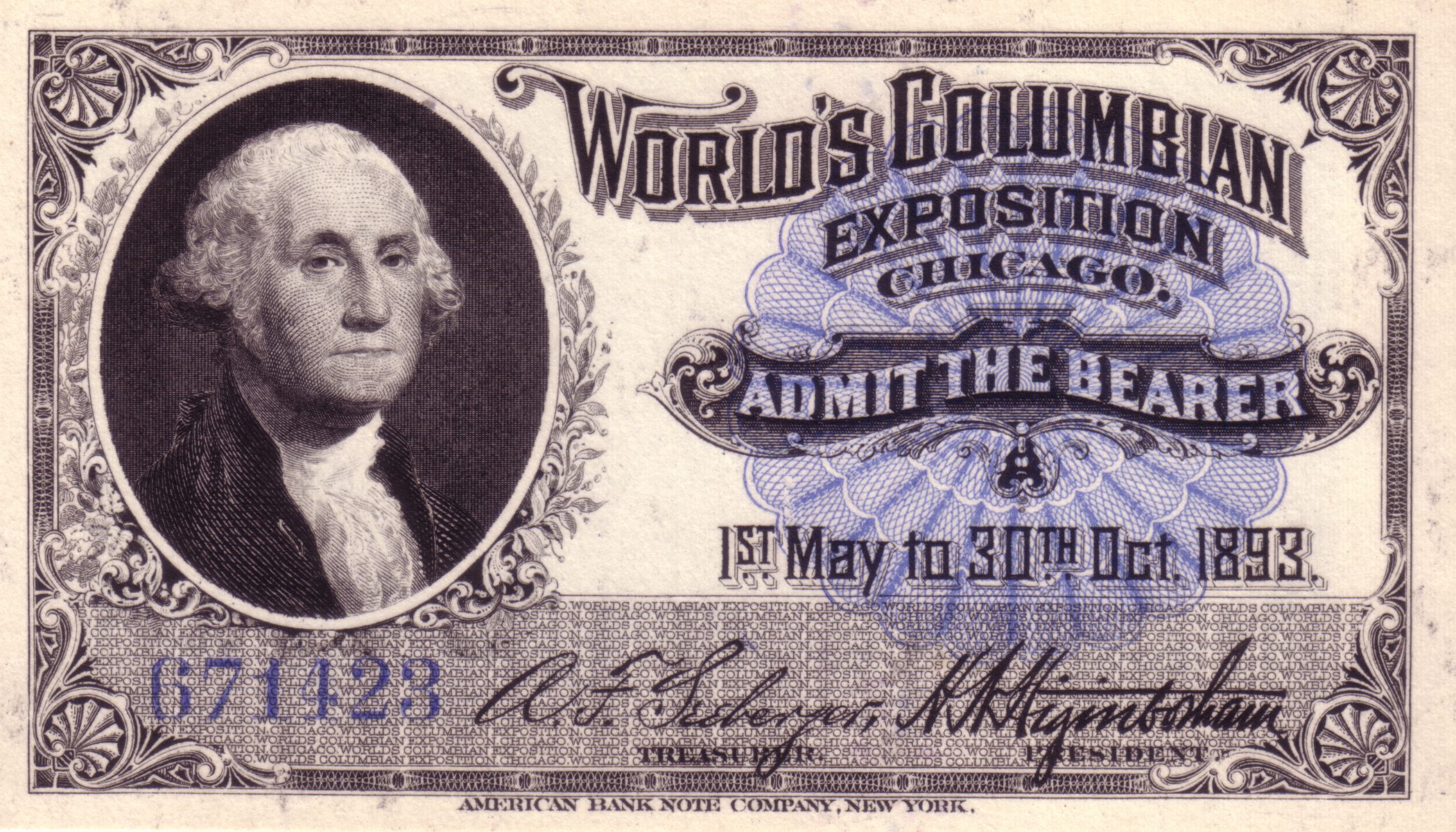

George Washington hopes you have a good time at the fair, seriously.

Out of the tens of millions of people who attended the fair, only a lucky 60,000 managed to get their hands on a ”portrait ticket.” These detailed notes served as season passes for exhibitors, organizers, press members, and other insiders. Engraved with great detail to prevent counterfeiting, each ticket featured either Washington, Lincoln, Columbus, or a stereotypical American Indian chief—figureheads who, taken together, were meant to represent various stages of the country’s history.

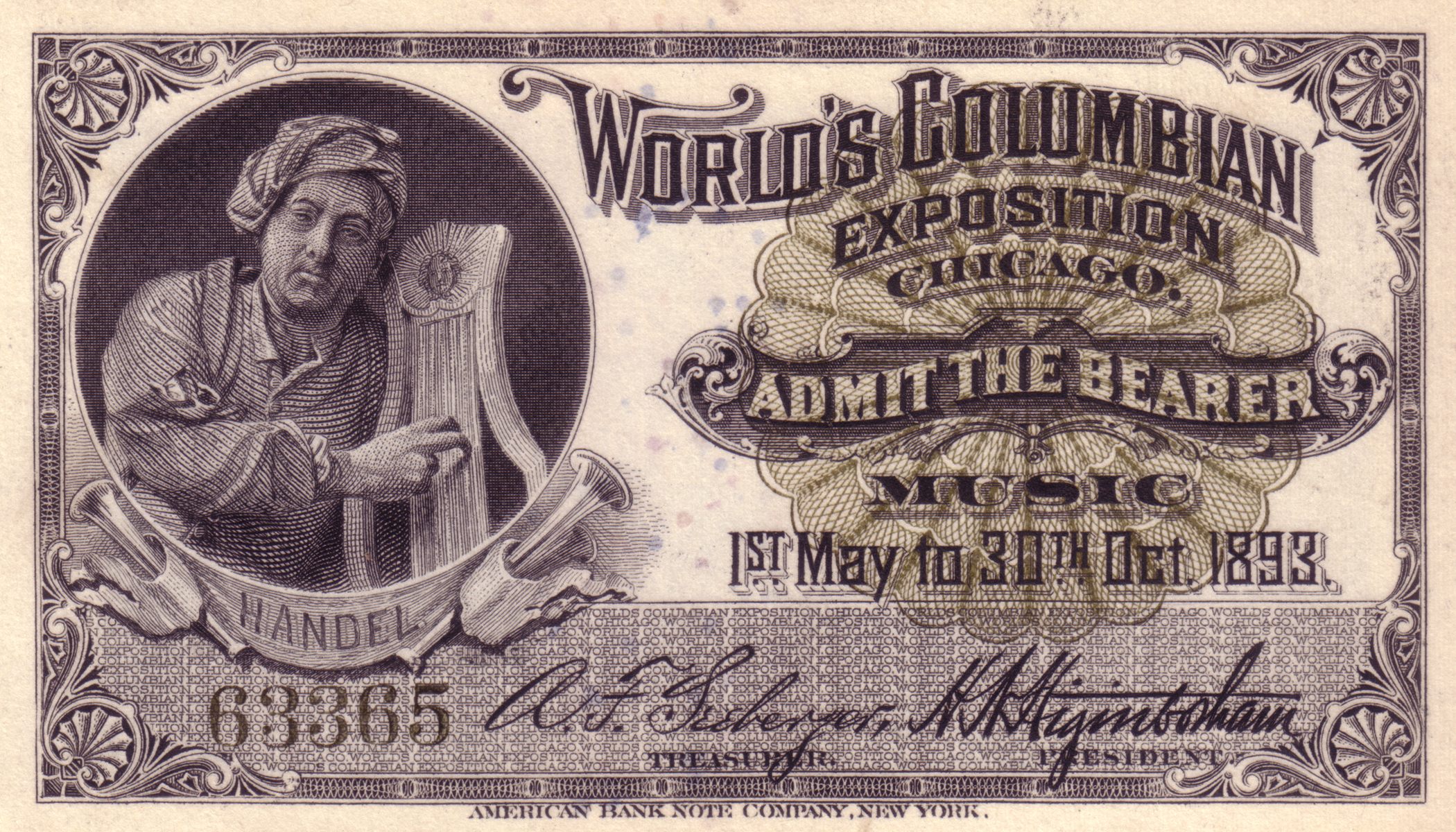

German composer George Frideric Handel also got his own ticket, because his music was played throughout the fairgrounds.

German composer George Frideric Handel also got his own ticket, because his music was played throughout the fairgrounds.

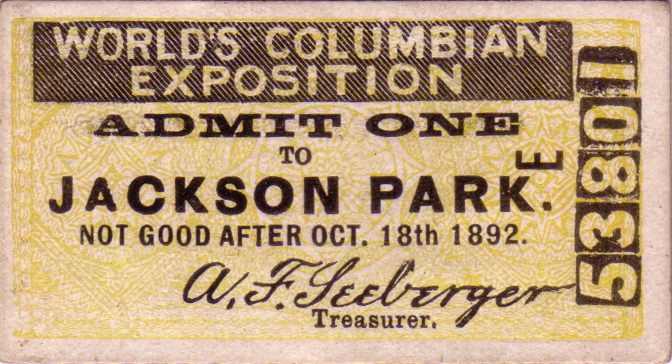

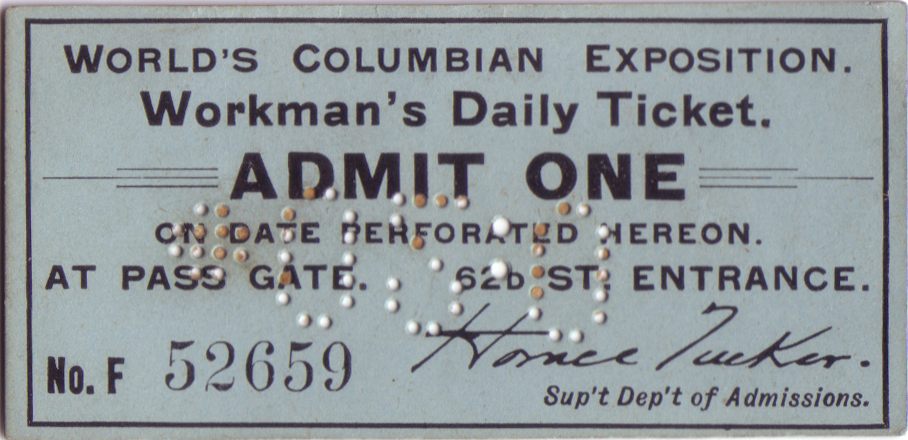

One-day Tickets

Tickets were about the size of a playing card.

Before the fair even started, people paid 25 cents to watch the fairground construction. Once it opened, single tickets cost 50 cents, the equivalent of about $14 today (kids got in for half price). “A great army” of workers manned the hundreds of ticket booths, windows and turnstiles, led by Department of Admissions Superintendent Horace Tucker, whose signature was printed on every ticket. Wide-ranging “special days,” named after states and countries, and more esoteric themes (“Bohemia Day”; “Stenographer’s Day”) got their own collect-em-all ticket designs.

This ticket belonged to a construction worker, and was stamped with the relevant date.

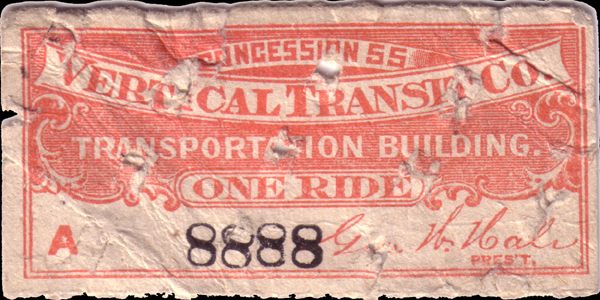

Exciting Infrastructure

Mr. S.H. Hale’s Vertical Transit Co. installed a bank of eight elevators in the Transportation Exhibit. One guidebook wrote that the elevators ”naturally form a part of the exhibit… as they also carry passengers.”

Mr. S.H. Hale’s Vertical Transit Co. installed a bank of eight elevators in the Transportation Exhibit. One guidebook wrote that the elevators ”naturally form a part of the exhibit… as they also carry passengers.”

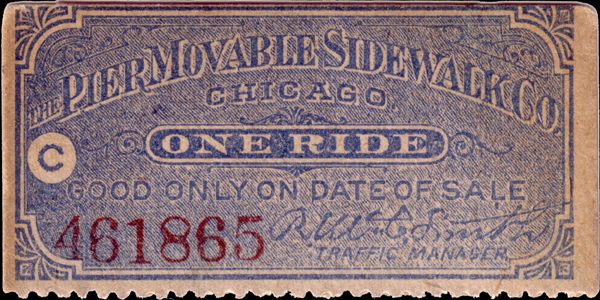

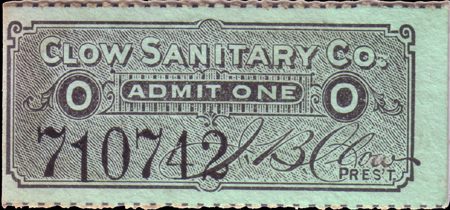

Many inventions that now seem utilitarian had their first large-scale deployment at the fair—supporting such a large number of people required banks of elevators and the first-ever moving sidewalk (along with the first-ever pay toilets). One whole hall was devoted to electricity, which was so new and exciting that one of the more popular exhibits was just a mockup house with enough electrical appliances to ensure ”no occasion for lighting a match in it for any purpose whatsoever.”

When it wasn’t suffering one of its frequent breakdowns, the Moveable Sidewalk went six miles per hour, and carried people from the end of the pier onto the fairgrounds.

When it wasn’t suffering one of its frequent breakdowns, the Moveable Sidewalk went six miles per hour, and carried people from the end of the pier onto the fairgrounds.

James B. Clow provided a cleaner experience than public toilets (and this florid ticket) in exchange for five cents.

Collectible Coins

The Air-Ship Chicago, also known as the Captive Balloon, gave guests an aerial view of the fairgrounds until it was brought down by a gale.

Savvy fair promoters offered collectible medallions to help fairgoers remember their experiences. (The Expo also marked the invention of elongated coin machines that print designs onto flattened pennies.) Other medals honored particular events or organizers—though most just sported the face of the Expo’s namesake, Columbus.

A medal honoring Bertha Palmer, the president of the Expo’s Board of Lady Managers. The Board was in charge of putting together the Women’s Building, which was designed by Sophia G. Hayden, the first female graduate of MIT’s School of Architecture.

The “Champion Load of Logs” medal commemorated one of Michigan’s contributions to the Expo—a 33-foot-tall log pyramid considered “one of the wonders of the world.”

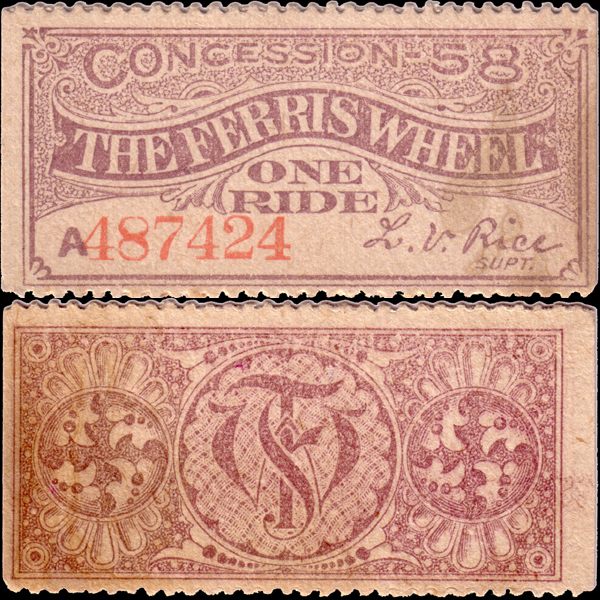

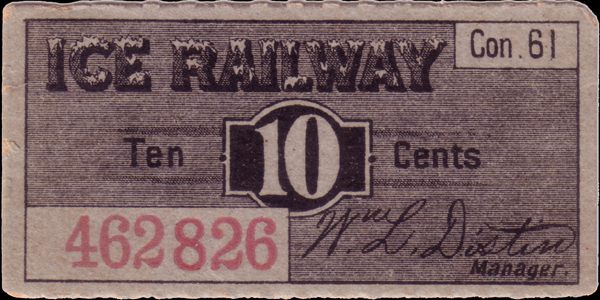

Midway Tickets

Of all the inventions displayed at the Columbian Expo, the Ferris Wheel was the flashiest. Fifty cents got you two revolutions, and a certificate asserting you had really ridden it.

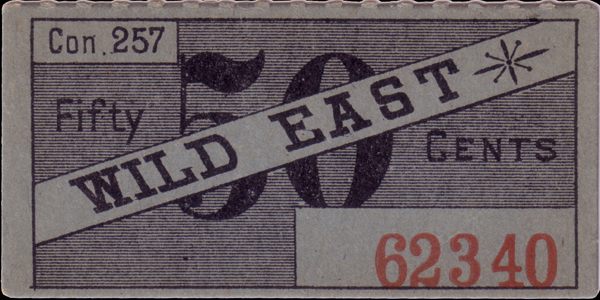

The fair was laid out according to its designers’ ideas of the progression of civilization: the grandiose exhibition palaces, like the Agricultural and Machinery Buildings, were built along the shore of Lake Michigan, while the “less evolved” Midway—a riot of amusement park rides, concessions, and corporate-sponsored ethnographic exhibits—jutted out from the main fairgrounds like a crank handle. Most Midway attractions had separate admission fees, and some fairgoers mortgaged their homes in order to finance the complete experience.

The Ice Railway was originally meant to be a fairground transport system, but was turned into an amusement park ride.

A concession ticket for the “Wild East,” an ethnographic exhibit staffed by Bedouin horsemen and the most direct competition for the Wild West show Buffalo Bill set up just outside the fairgrounds.

Chocolate companies went a little nuts at the Expo—the Stollwerck brothers of Germany built a 38-foot chocolate temple, and a Dutch company served free samples out of a windmill. Chocolat Menier stuck with a regular old pavilion.

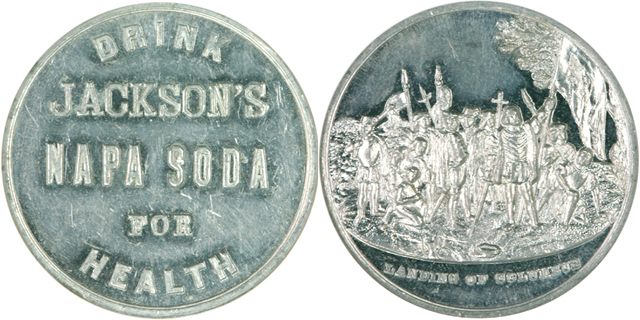

Advertisements In Disguise

Columbus shills for soda water.

Other medallions were just as shiny and collectible, but served as advertisements for the many things guests could buy at the Expo. Dozens of new products were introduced to a mass audience, including Hershey’s chocolate, hamburgers, spray painting, picture postcards, zippers, and carbonated diet soda.

Joseph Nason invented steam heating, which experienced a popularity surge in the 1880s.

A medallion that advertises for itself. “The wonderful metal aluminum” was being touted as the next big thing American stuff could be made out of.

A medallion that advertises for itself. “The wonderful metal aluminum” was being touted as the next big thing American stuff could be made out of.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook