Does the thought of creamy, chewy wheat berries, roasted nuts, and dried fruit—spiced with cinnamon and sweetened with honey—make your mouth water? In the Eastern Orthodox Church, that’s a heretical move.

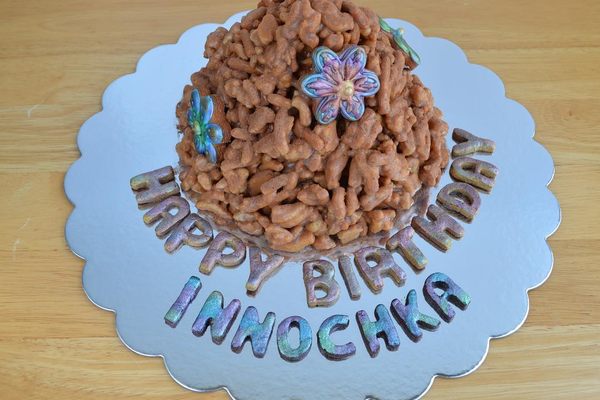

Orthodox Christian families honor the memory of deceased loved ones with a special dish called koliva. This ritual, common in the Balkans (especially Greece) and Russia, employs the whole grain of the wheat plant to symbolize everlasting life. These starchy “berries” give koliva a firm bite and subtly nutty, earthy flavor.

Mourning families prepare the dish by adding raisins, which represent life’s sweetness, as well as spices like cinnamon and anise as symbols of plenty. They then mix in some combination of sesame seeds, almonds, parsley, pomegranate seeds, honey, Jordan almonds, and ground walnuts. Topping the commemorative dish is a blanket of confectioner’s sugar, to represent resurrection and abundance. A cross often graces the top, sometimes accompanied by the initials of the deceased.

Scholars believe koliva dates back to the early years of Christianity, but some medieval manuscripts assign the dish divine origins. A 14th-century Byzantine Greek service book includes a story in which the pagan Roman emperor Julian sought to undermine Lent by contaminating Constantinople’s food supply with animal blood. Saint Theodore came to the rescue, revealing the recipe for koliva to an archbishop in a dream and thus saving Christians from eating unholy food.

Today, Orthodox Christians make koliva to usher in Lent and for special Saturdays throughout the year, called Saturdays of the Souls. At memorial services, mourners serve it on doilies. They also bring the dish to church at designated times throughout the year following a funeral, and on subsequent anniversaries of a loved one’s death.

Despite koliva’s inventory of tasty ingredients, it is meant to be eaten solemnly in conjunction with rituals. As one Greek Orthodox woman wrote in response to an article that showcased koliva as a dessert as well as a sacred dish: “It is prepared during requiem and memorial services for the departed, and not as the end of a stuffing feast topped with whipped cream! What’s next? Dinner at a cemetery?”

Written By

Madeleine Kenyon

Madeleine Kenyon

Sources

- blogs.bl.uk/digitisedmanuscripts/2017/03/a-heavenly-recipe.html

- www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/gfc.2007.7.4.84?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

- web.archive.org/web/20100916201745/digicoll.library.wisc.edu/cgi-bin/HistSciTech/HistSciTech-idx?type=turn&id=HistSciTech.Cyclopaedia01&entity=HistSciTech.Cyclopaedia01.p0420&q1=colyba

- books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=z3DbXtnB0dwC&oi=fnd&pg=PR7&dq=koliva+greek+funeral+food&ots=GADABG7Zhu&sig=dhnJMrwX5MFZNW0TjWYHlHbTfoA#v=onepage&q=koliva&f=false

- www.researchgate.net/profile/Katherine_Burlingame/publication/299594488_Whispers_of_a_Common_Past_Mapping_Intangible_Heritage_of_the_1923_Greek_and_Turkish_Population_Exchange/links/5701553008ae650a64f8c149/Whispers-of-a-Common-Past-Mapping-Intangible-Heritage-of-the-1923-Greek-and-Turkish-Population-Exchange.pdf

- www.thespruce.com/what-are-wheat-berries-3376779

- latimesblogs.latimes.com/dailydish/2009/04/the-importance-of-koliva.html