About

Salzwelten Altaussee, Austria’s largest active salt mine. It is remarkably old, having been mined almost continually since 1147. During World War II, the rock salt tunnels were turned into a storage facility holding hundreds of pieces of artwork stolen by Nazis.

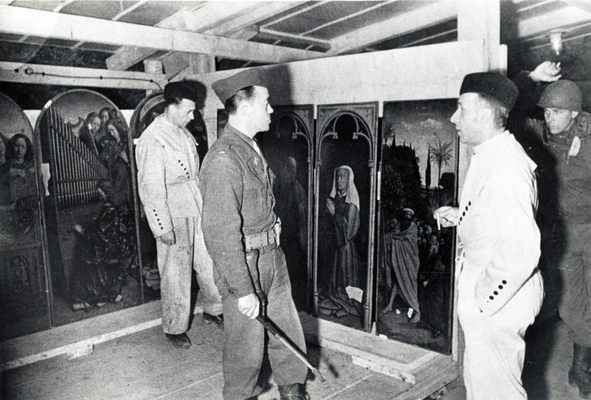

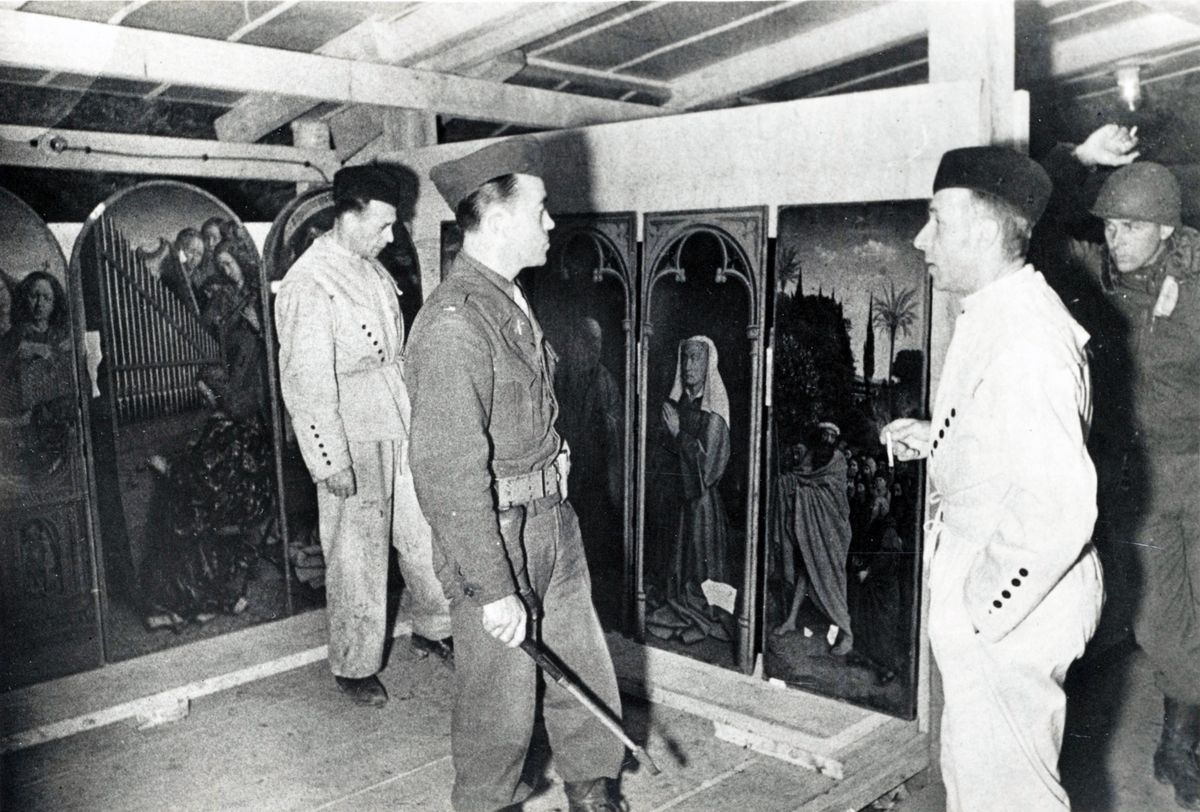

The salt mine became Nazi Germany's art repository in 1943, housing artwork looted from some of the most important public and private collections in Europe. Most of the pieces were destined for the prospective Führermuseum, planned for Hitler's hometown of Linz, Austria. Ultimately, it came to be the hiding spot for nearly 8,000 paintings, drawings, and sculptures. The collection contained some of the most famous and valuable pieces of art in Europe, including paintings by Vermeer, Breughel, and Rembrandt, the Ghent Altarpiece by Jan and Hubert van Eyck, the monumental bible from St. Florian’s Monastery, the Rothschild family jewels, and Michelangelo’s Madonna of Bruges, stolen from the Church of our Lady in Bruges in 1944.

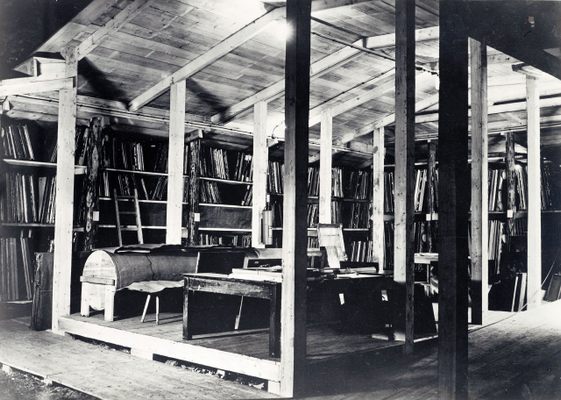

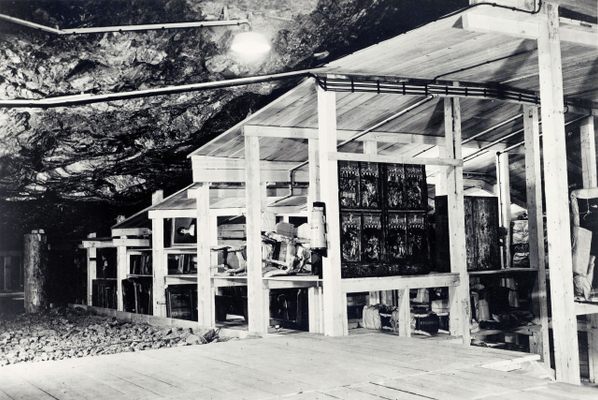

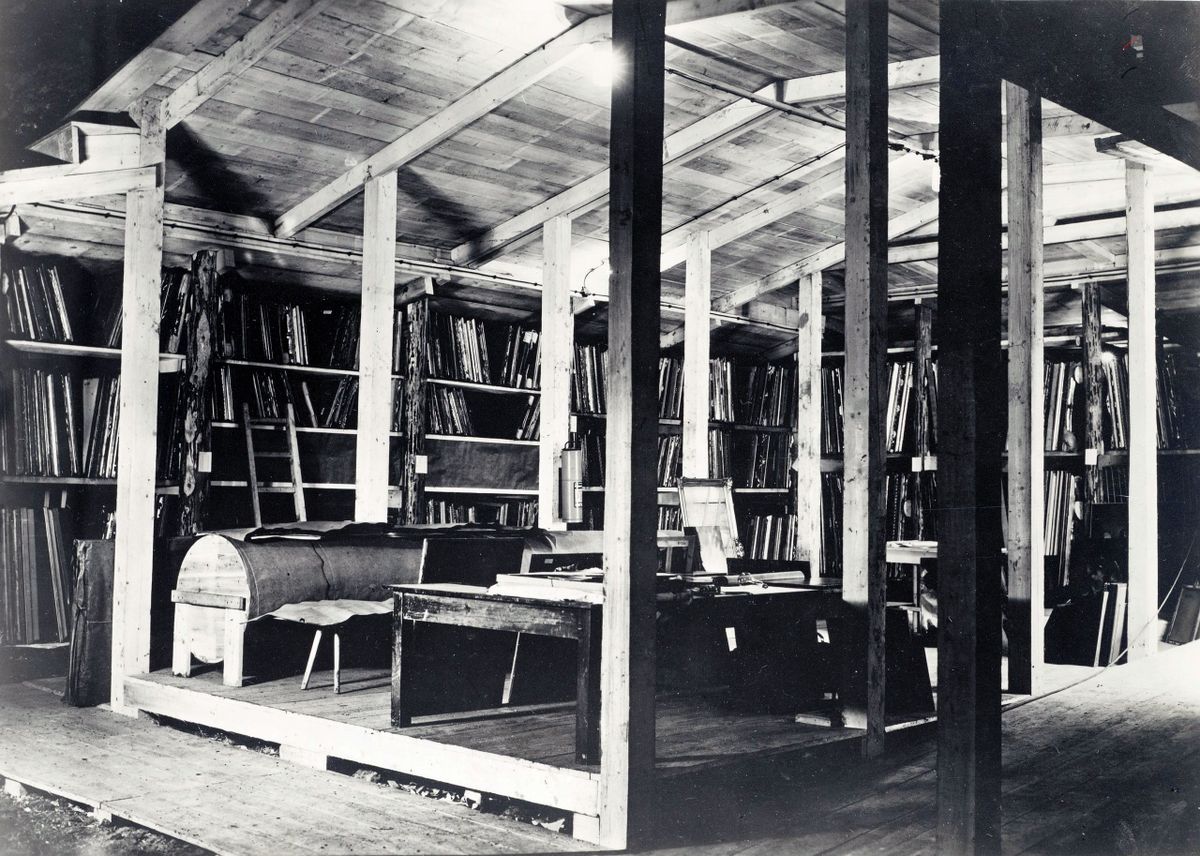

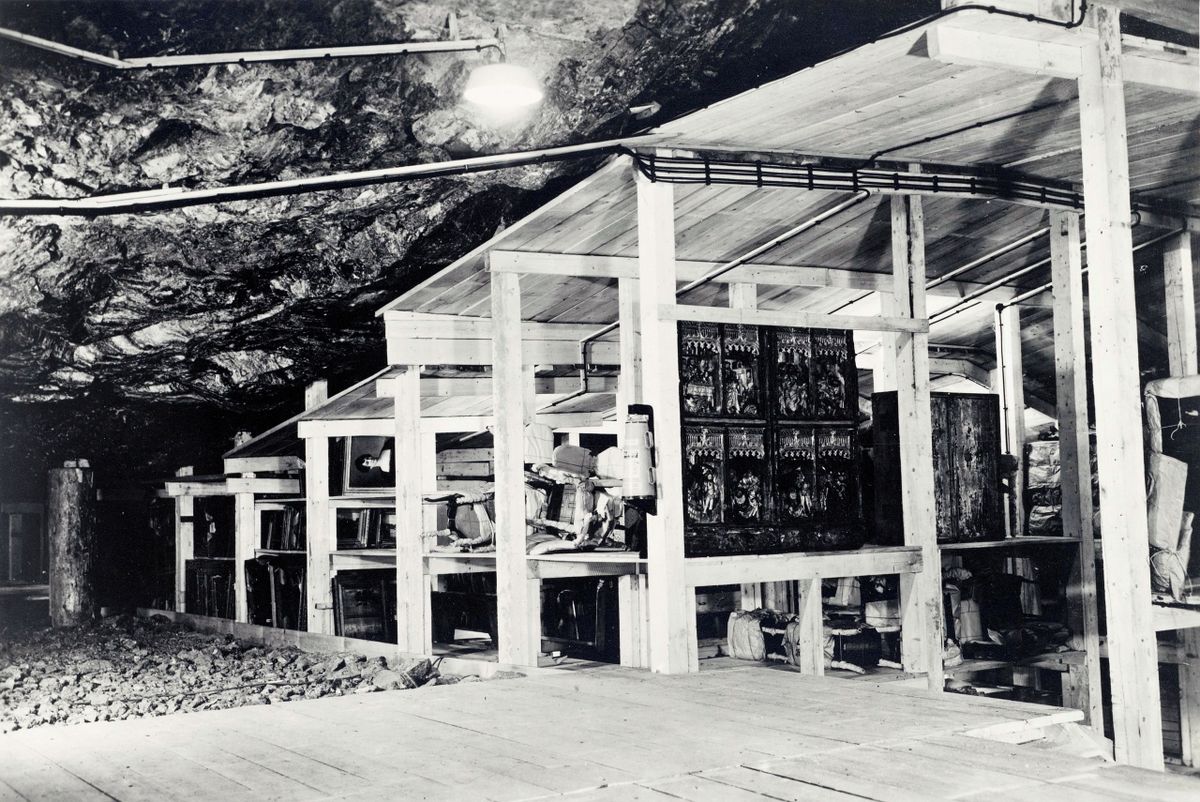

The conditions in mines were ideal for storing art. The rock salt tunnels have a consistent interior temperature of eight degrees Celsius (46 degrees Fahrenheit) and they were deep underground, sometimes up to 800 meters, which provided protection from aerial bombing. Altaussee had 137 of these tunnels, all able to fit hundreds of pieces of art. The climate in these tunnels was also perfect for conservation, as they were cool, dark, dry, and, most importantly, stable. According to the Monuments Men and conservator George Stout, who was present at many of the recoveries found in mines, they were relatively dry with a low average relative humidity of 40 percent.

As the Allied and Soviet advances were nearing Berlin in 1945, a desperate Hitler issued the Nerobefehl (Nero Decree), ordering the destruction of German infrastructure to prevent the Allied advance. It was also interpreted to extend to the art hidden in Altaussee. At that time, the salt mine was under the authority of August Eigruber, the regional head of the Austrian Nazi party. Even after the rescindment of the decree, he ordered eight bombs to be placed inside the tunnels, but disguised them by placing them in crates labeled “Caution - Marble - Do Not Drop.” However the general director of the mine, Dr. Emmerich Pöchmüller became suspicious of these new crates, and his team instead moved them out of the mine in the dead of night. Using a system of small explosive charges, they blasted the entrance to the mine closed, sealing the treasures inside, to wait for the arrival of the Allies.

The Monuments Men and Women (the serving personnel who worked in the Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives Unit) heard about Altaussee through Herman Goering’s past second-in-command Hermann Bunjes. Wanting to travel to Paris with his family safely, Bunjes told the Allies about Hitler’s hiding place, and Monuments Men Maj. Robert Posey and Pfc. Lincoln Kirstein arrived in Altaussee the second week of May 1945. The Allies had no time to lose, as the surrounding area would soon be turned over to the Soviets. This led to a huge scramble to evacuate as much art as possible from Altaussee.

By July 1945, it was reported that 6,577 paintings, 230 drawings and watercolors, 954 prints, 137 sculptures, and 129 pieces of arms and armor had been removed from the mine. In addition to these pieces of art, there was also furniture, tapestries, and cases of archival objects, books, and unidentified content. These pieces were relocated to a number of collecting points across Germany, to begin the long process of restitution.

In 2019, the mine opened “The Fortune of Art” permanent exhibition at the location where Hitler’s looted art had been hidden. There you can find, among other exhibits, a cast of Michelangelo’s Madonna of Bruges. The mine is still active, and has 30 active mining sites and 57 employees, with brine production at 500,000 tons of salt a year.

Related Tags

Community Contributors

Added By

Published

May 4, 2022