About

To see the sprawling 230-foot Bayeux Tapestry is to be endlessly enthralled by the power of art and storytelling. As if woven with magic, this tapestry bewitches the viewer, drawing him or her into the flowing narrative of a true tale of medieval intrigue and bloody warfare that changed the course of European history.

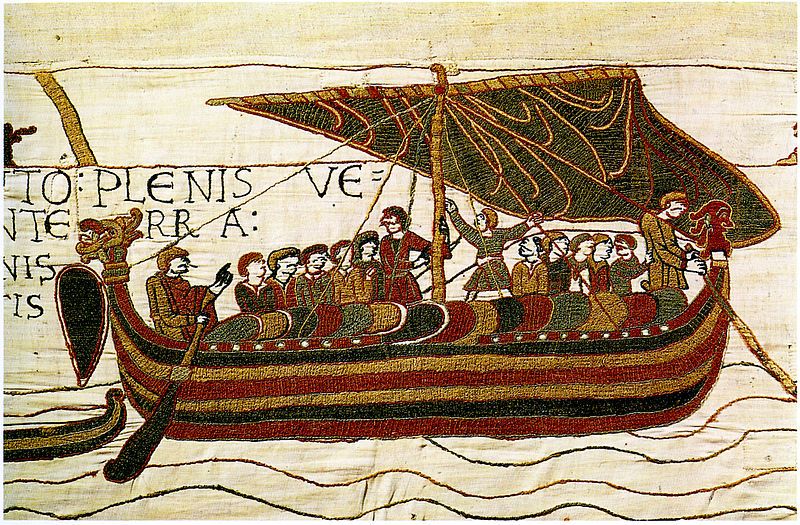

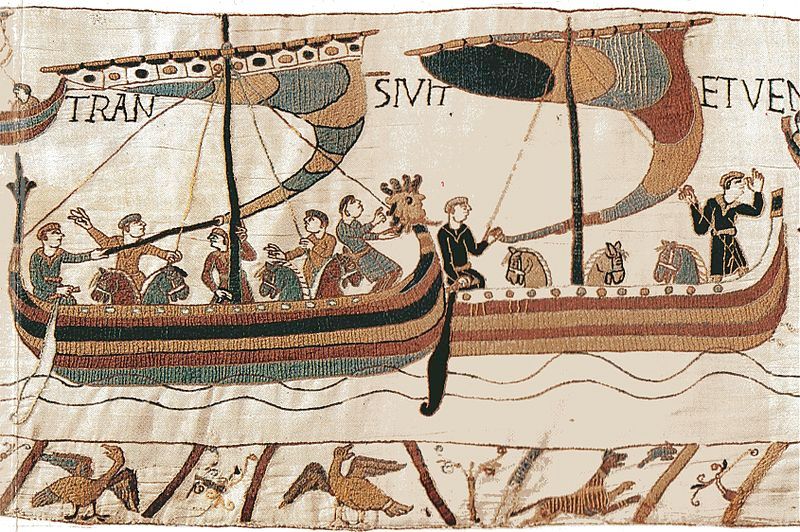

At almost 230 feet (70 meters) long and 20 inches (50 centimeters) tall, the embroidery is one of the largest ever made during the early medieval age. It winds around a wide gallery in a serpentine fashion in France's Museum of the Bayeux Tapestry, where visitors can appreciate every small detail through the glass of its exhibit case.

Historians believe it took a decade of daily weaving for artisans to complete this masterpiece, which was woven by hand from wool yarn and linen cloth. Although the exact origin of the tapestry remains a mystery and the subject of scholarly debate, it is widely believed to have been commissioned by the half brother of William of Normandy, the Bishop Odo of Bayeux, who was also a knight whose prowess on the battlefield was renowned.

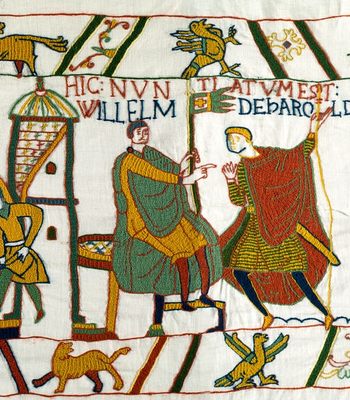

It is evident that the purpose of this extraordinary embroidery was both to commemorate the battle and to be used as a piece of propaganda to legitimize and aggrandize the Norman dynasty. In 50 sequential scenes of barbaric beauty, the embroidery relates the story of the fierce battles for the English throne. It portrays the lead-up to the Norman conquest of England in 1066: eerie omens, the carnage of the Battle of Hastings, the defeat and gruesome death of the ill-fated King Harold of the Saxons, and finally the victory of Duke William "the Conqueror" of Normandy who would take the English crown.

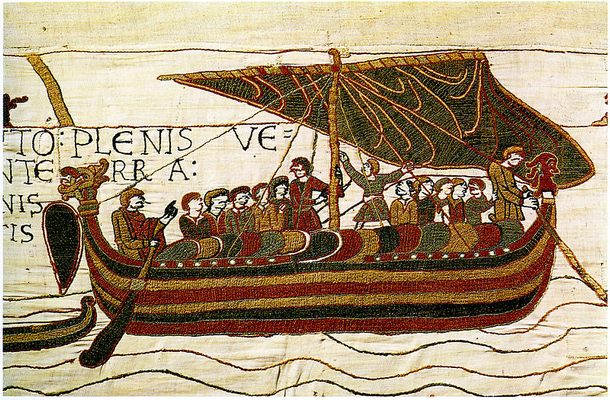

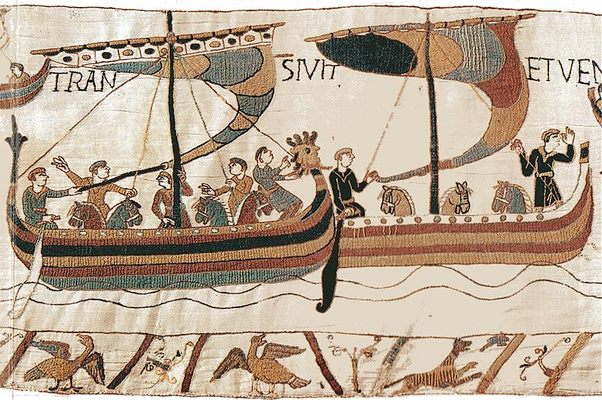

The attention paid by the craftsmen and craftswomen to the tiny details in each scene is astounding. The tapestry depicts men training in sword-fighting and combat, ships being built, men rolling up their trousers to wade through the sea and board the boats, and the transport of war horses from France across the English channel. Also here are scenes of a more lighthearted nature, such as the hunting of hares with falcons, games of hockey and chess, feasts, drinking, and merriment. The tapestry even shows characters playing practical jokes on one another, all of which make this piece of art a surprisingly human one.

Elements of the supernatural and mythological are included throughout the tapestry, too. A strange and colorful bestiary of heraldic birds, beasts, and entities cavort along the margins as if dancing to the beat of music. A fiery image of Halley's Comet can be seen in the top margin passing above Saxon figures at Harold's court, who gasp and point in wonderment. This celestial body trailed through the sky in 1066 in the months before the invasion and was interpreted by many as a sign from God of the impending victory of the Normans.

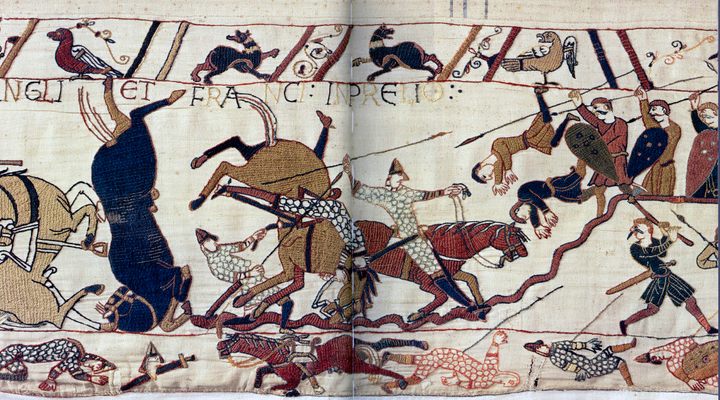

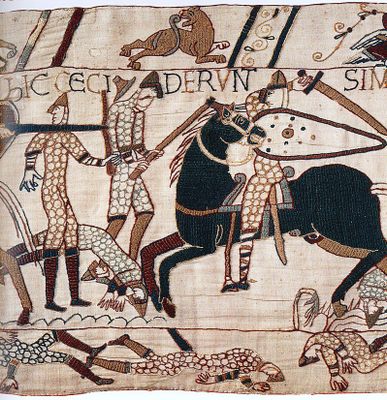

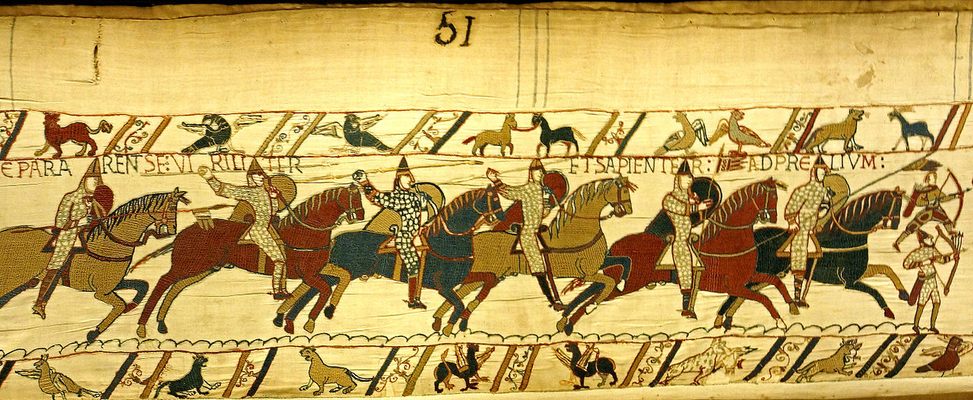

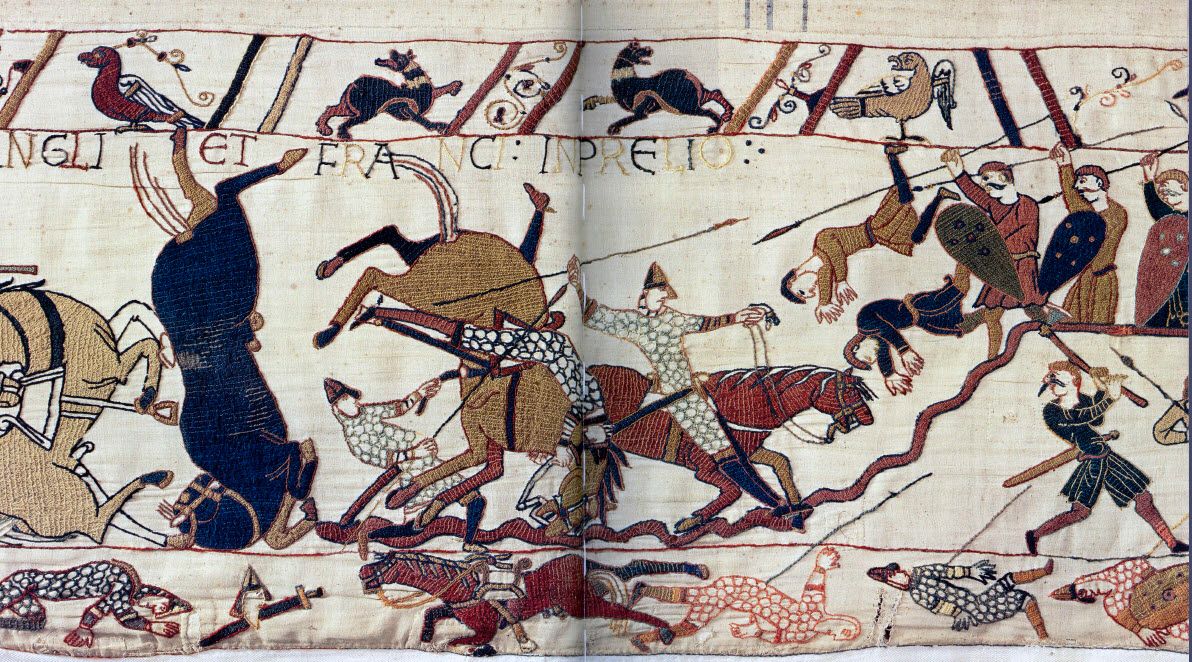

But the real highlight of the tapestry is its scenes of battle, which capture the grittiness and totality of war and its aftermath. Archers fire arrows into the sky that land on shields or men, axes and war hammers cleave skulls or limbs, while swords or spears are run through the bodies of warriors and warhorses. The Norman cavalry charge clashes into the human wall of Saxon warriors, breaking through in some places and being repelled in others. But far from invincible warriors, the Norman soldiers themselves are shown as just as mortal and fallible as their Saxon foes and the dead and dying of both armies litter the battlefield.

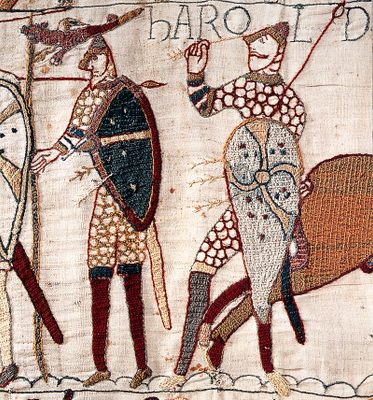

An armor-clad figure labeled as King Harold is shown grimacing as an arrow passes through his eye and brain, killing him in the manner that the chronicles describe he died. Intriguingly, the tapestry seems to suggest that he was a tragic figure, which perhaps indicates that he was seen as an admirable adversary by the conquerors of his people. William the future king, on the other hand, is shown with a degree of aloofness and clinical distance. He is portrayed as a composed and able military leader who rides with a dignified air with his men during cavalry charges and is wearing his new crown by the end of the battle.

Related Tags

Know Before You Go

The museum is open from 9 a.m. to 6:30 p.m. (to 7 p.m. in summer) and tickets are 7.50 euro. (Tickets unfortunately can only be bought at the site.) The town of Bayeux also has a museum and many war memorials from more recent world history to see, as it was the first landing point of the Allied forces during the invasion of Normandy in World War II.

Community Contributors

Added By

Published

February 22, 2019