About

Surrounded by prairie, farms, and wetlands, a modest ridge of woodland in southeastern Wisconsin might not seem noteworthy, but its story goes back about 430 million years and stretches across North America’s heart. To reach Brady’s Rocks, take a short spur off the 1,200-mile-long Ice Age National Scenic Trail, which leads up the ridge to a jumble of small cliffs, none much taller than the average hiker. Briefly quarried by an Irish immigrant named Michael Brady in the mid-19th century, these rock formations represent the southernmost surface exposure of a formation born in an ancient sea and so strong it cleaved a glacier in two: the Niagara Escarpment.

You may not have heard of the Niagara Escarpment, but you’ve almost certainly seen it. The most visible section of the massive geological feature sits on the U.S.-Canada border, between Ontario and New York State, where millions of gallons of water spill over the imposing black rock walls of Niagara Falls. The falls gave the escarpment its name, but they’re only a fraction of its span.

On a map of North America, follow an arc of cliffs and ridges northwest of the falls, along Ontario’s Georgian Bay and Manitoulin Island, curving around Michigan’s Upper Peninsula and then southwest through Wisconsin’s Door Peninsula. From there, follow it south along the east side of Lake Winnebago, where locals call it “The Ledge.” Moving into southeastern Wisconsin, the feature seems to disappear, buried beneath layers of glacial till and other debris dumped by receding ice about 15,000 years ago near the end of the last ice age. The arc of ancient rock actually continues below the surface into Illinois, but its southernmost exposures are in Wisconsin’s Waukesha County, mostly through rock cuts in small quarries. Brady’s Rocks, however, are exposed naturally along the top of the small ridge.

Like the rest of the Niagara Escarpment, Brady’s Rocks began as sediment deposits in an inland sea during the Silurian Period, about 430 million years ago. The lime-rich mud eventually formed dolostone, or dolomite. Over millions of years, tectonic forces pushed this massive arc of rock upward even as erosion tried to grind it down. The scouring forces of water, wind, and ice succeeded in creating gaps in the curving ridge here and there. Along the eastern side of Wisconsin, however, the rock formation was strong enough to split the southern edge of the Laurentide Ice Sheet about 30,000 years ago, creating two glacial lobes. One lobe carved out Lake Michigan and the other created Wisconsin’s Green Bay, two bodies of water that now dramatically frame the state’s most visible portion of the Niagara Escarpment. While Brady’s Rocks may not be as stunning as the 200-foot cliffs in the state’s northeast, they're no less geologically significant. They're ecologically important, too: The modest vertical rock faces are home to several rare fern species that survived the tumult of the last ice age.

The entire escarpment, by the way, is technically a cuesta, a geological term derived from the Spanish word for “slope.” Cuestas could be thought of as tilted ridges: One side is much steeper than the other, less dramatic slope. It’s the result of harder layers of rock resisting erosion better than the softer layers beneath.

Related Tags

Know Before You Go

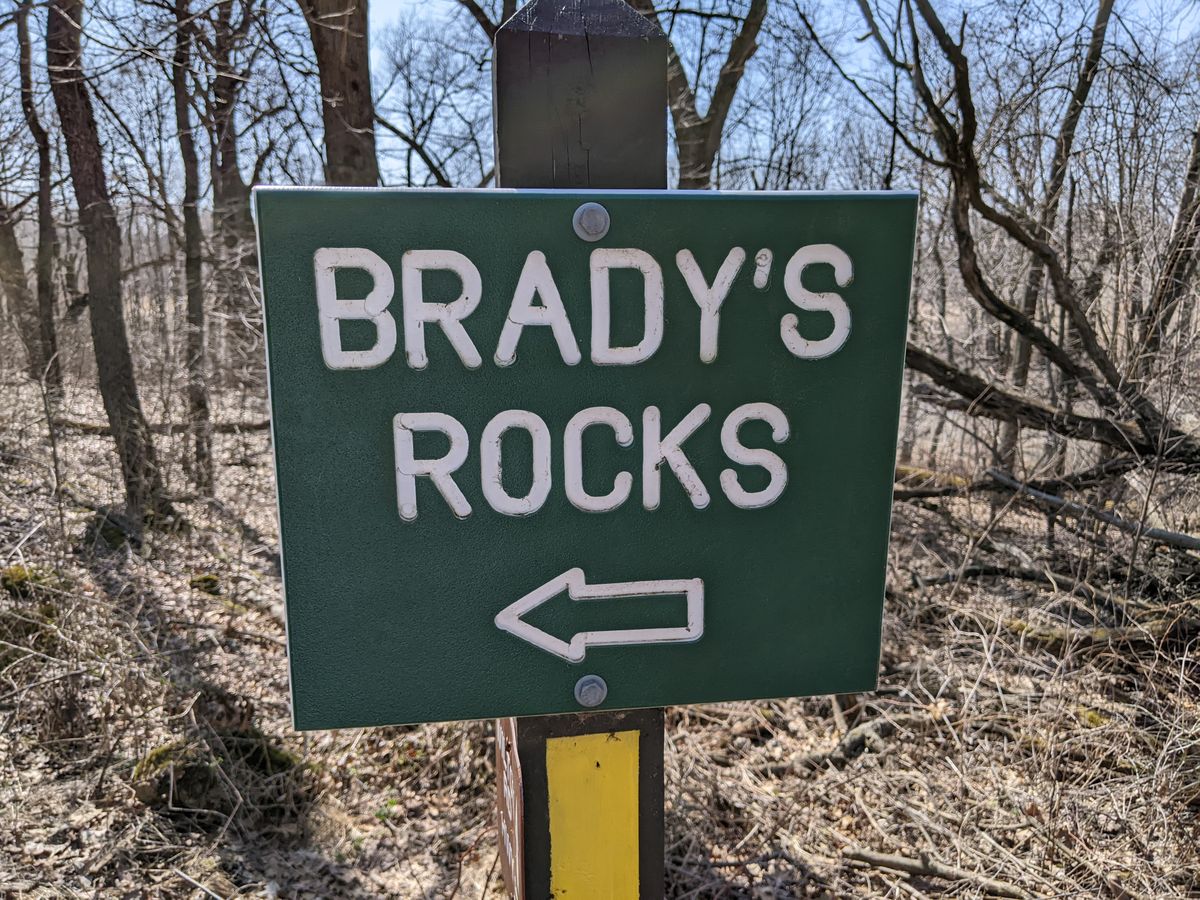

Brady’s Rocks are clearly marked just off the Ice Age National Scenic Trail (IANST), which zigzags across Wisconsin. There is no public transportation to the rocks, but there are several small, unmarked, and unpaved public parking lots that provide access to the IANST on the west side of Highway 67, also known as the Kettle Moraine Scenic Drive along this portion.

The closest lot to Brady’s Rocks trailhead is just north of the intersection with Wilton Road. From the lot, follow a grassy trail west to the yellow-blazed IANST and then turn south. The trail heads into woodlands, dipping to a small plank bridge and then gently rising to follow a ridge. The sign marking the white-blazed spur to Brady’s Rocks is about 500 meters, or a third of a mile, from the parking lot.

Brady’s Rocks area is home to several rare species of ferns and snails, and visitors should stay on the trail to avoid damaging the fragile ecosystem.

Published

April 27, 2023

Sources

- https://www.iceagetrail.org/event/waukesha-milwaukee-co-chapter-trail-improvement-day/img_0625/

- https://minds.wisconsin.edu/handle/1793/37954

- https://wgnhs.wisc.edu/pubshare/GS22.pdf

- https://wgnhs.wisc.edu/wisconsin-geology/major-landscape-features/niagara-escarpment/

- https://www.waukeshacounty.gov/globalassets/parks--land-use/planning-zoning/chapter-3-final-ag-cultur-natur-print-ready.pdf