About

It's hard to look past the thousand pounds of brown bear hunched like a boulder in the middle of rushing water, lazily munching on the salmon it has just pulled from the river. But tear your eyes away from the sight of one of the famously fat bears who congregate at Brooks Falls and you'll see something arguably more intriguing.

Nearly everywhere you look along the steep, ancient banks of the Brooks River—a two-mile waterway in the heart of Alaska's Katmai National Park—you'll notice slumps of earth within the dense spruce forest. Roughly rectangular in shape and about the size of your average sedan, each of these depressions, now strewn with lichen and overgrowth, marks the site of an ancient home. There are hundreds of them.

In fact, while the area is famous for having one of the highest concentrations of brown bears in the world, a half-mile stretch of Brooks River—right where the bears congregate in summer and fall—is also home to one of the most densely-packed archaeological complexes in Alaska.

Over the past 5,000-plus years, several cultures have transited this area or established permanent towns along elevated river banks.

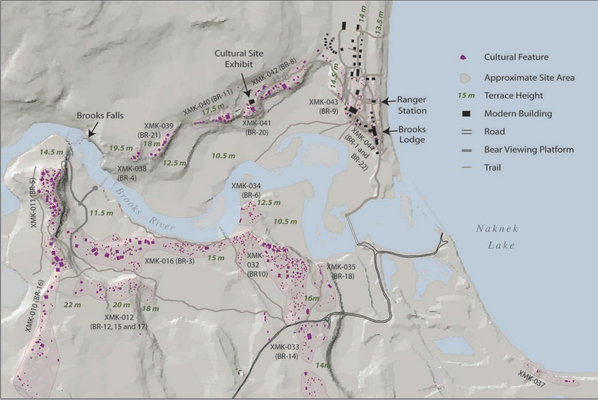

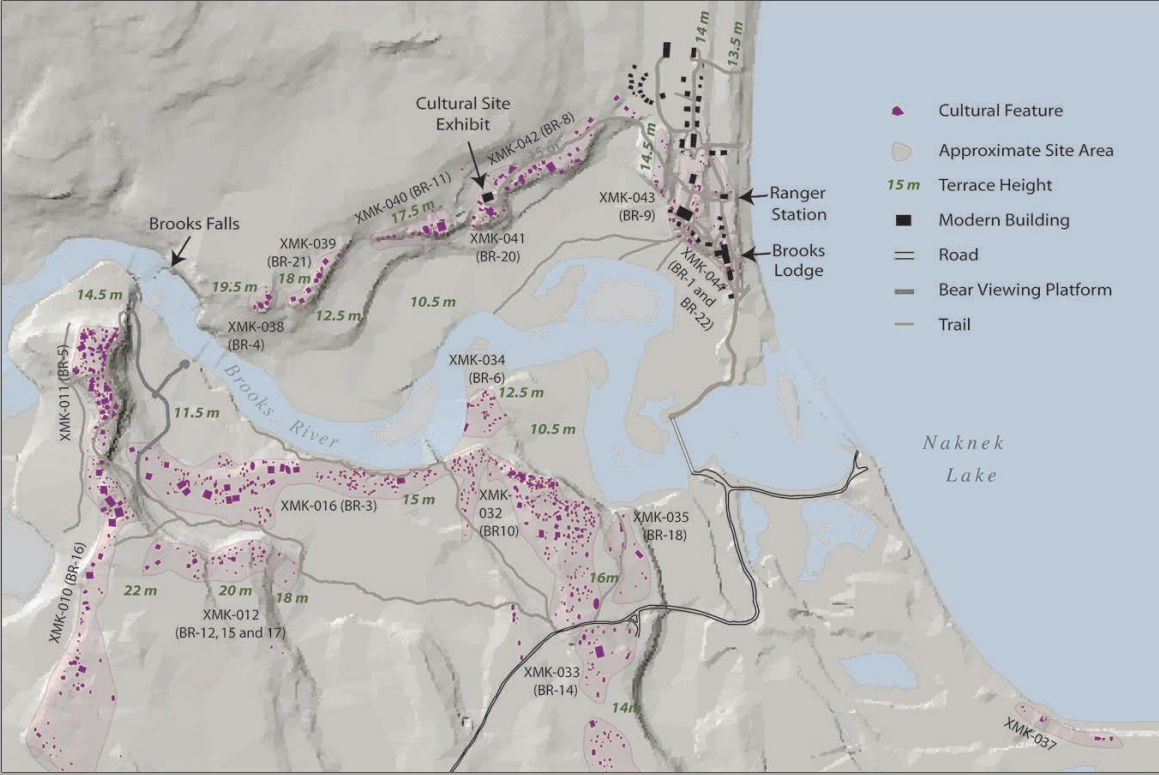

Survey work beginning in the 1960s has identified at least 20 different sites, most with multiple dwellings, along ancient terraces and other areas now several meters above the current course of the ever-shifting river. Red dots and squares crowd together on a map that shows the ancient homes and other structures identified so far. Together, they comprise the Brooks River Archaeological District, designated as a National Historic Landmark in 1993. The area stretches from the falls about half a mile east, to modern cabins and a ranger station.

Only a handful of the sites have been excavated—Alaska’s short archaeological field season happens to coincide with the river’s bear-iest period. It’s not unusual to see bears napping in the slumped home sites as if they were giant dog beds, and the trail out to a reconstructed home is criss-crossed with bear trails and dotted with fresh scat in summer.

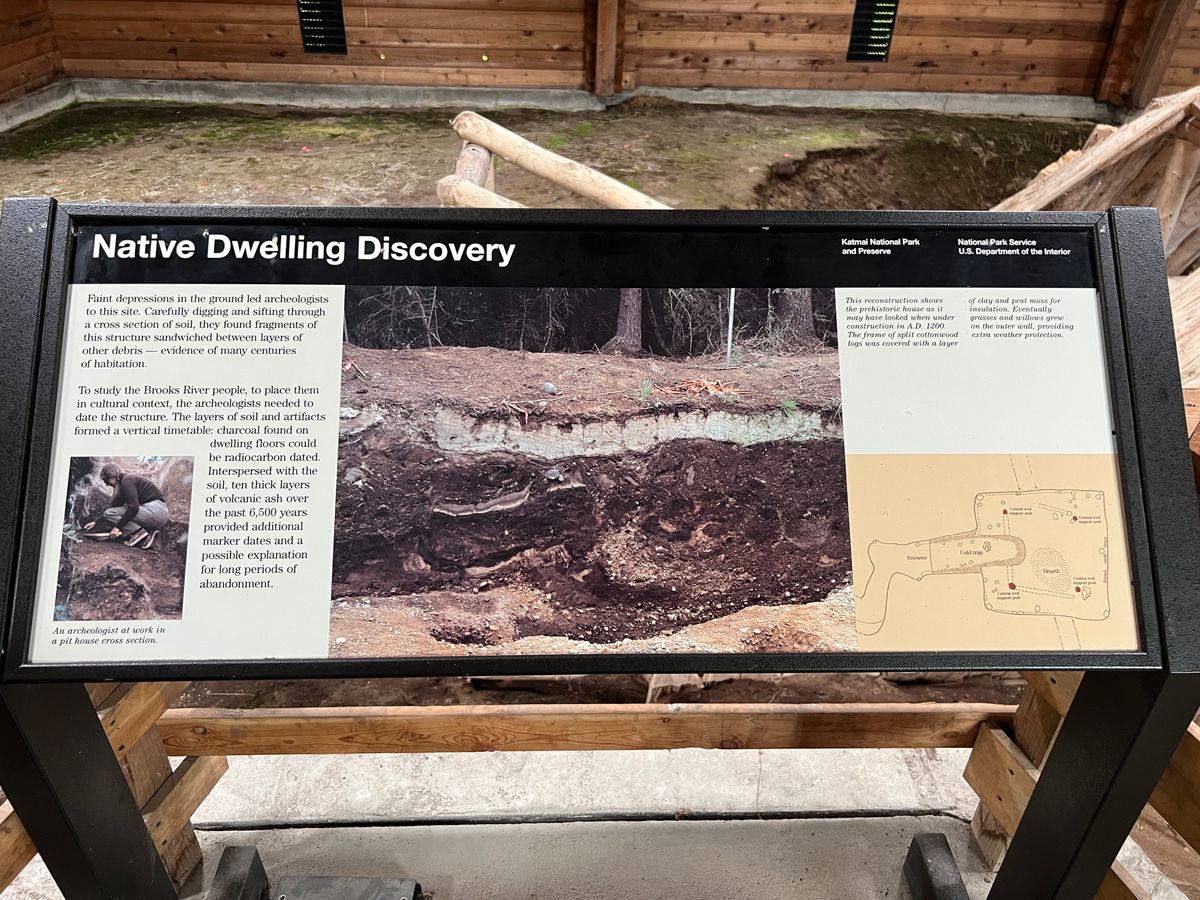

What archaeologists have uncovered is a fascinating and complex story of different cultures moving through the area at different times for different purposes. The oldest sites, going back more than 5,000 years, belong to hunters passing through seasonally in pursuit of migrating caribou. Artifacts recovered from this earliest period suggest Brooks River was frequented by two groups: one from the Alaska Peninsula stretching to the southwest and a second culturally separate group from deeper in the interior. After a period without any documented human activity, a third group appeared to settle along the banks about 4,000 years ago. Known to archaeologists as the Arctic Small Tool tradition thanks to the finely carved artifacts they left behind, these settlers built semi-permanent homes with stone-lined hearths and focused not on hunting but fishing. They vanished around 1200 B.C., however, and for several centuries it appeared that no one lived in the Brooks River area.

Around the year 400, a new group of people settled; their artifacts link them to a culture spreading southward from the coast—they used lamps fueled with seal oil, for example—but there are also some links to the earlier Arctic Small Tool tradition, suggesting a potential ancestral connection. Another major wave of arrivals came around 1100, when people from the north, with clay lamps and tools of polished slate, settled the area permanently. They stayed in tent homes during summer and, in winter, set up cozy pit houses that were similar to their predecessors.

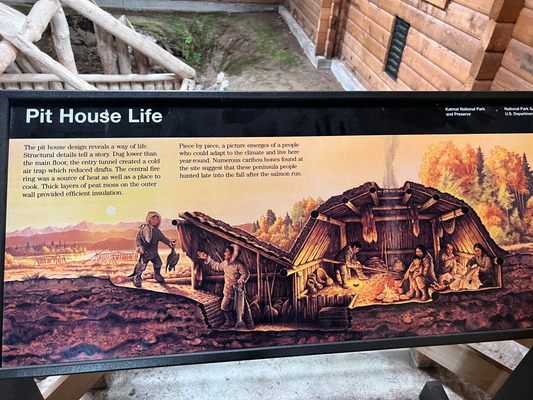

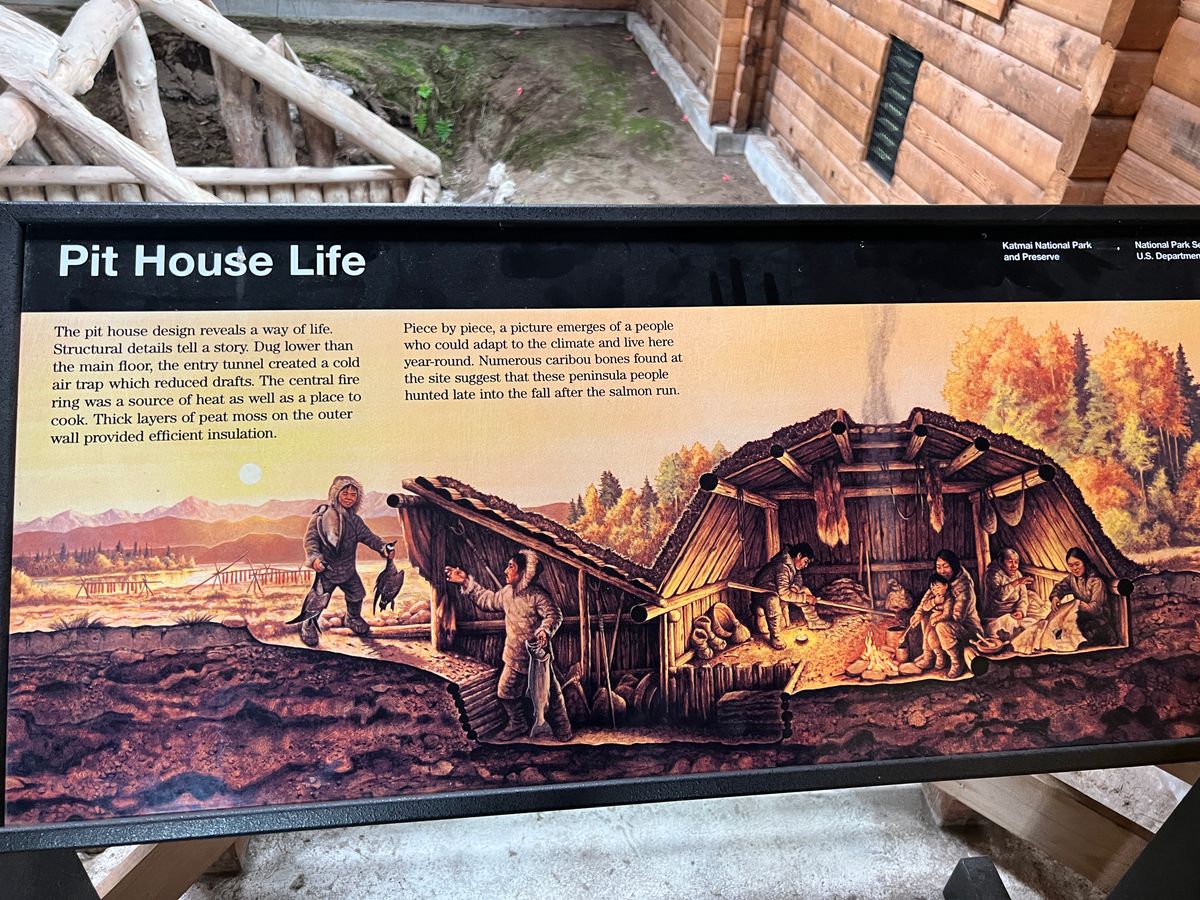

One of the pit houses from this later period has been excavated and reconstructed on its original site, with a modern wooden building over it to protect it from the elements (and curious bears). About the size of a single-car garage, the home featured a central hearth and an elevated sleeping area for increased warmth. It was built of split cottonwood logs, overlaid with sod and other material for impressive insulation.

Perhaps the home’s most ingenious feature was its cold trap: To access the home’s interior, visitors used a short, tunnel-like entrance that first sloped downward, collecting cold air as it sank, then rose to the ground floor of the semi-subterranean dwelling.

The reconstructed home was abandoned soon after it was built, around the year 1200, possibly because of flooding or ashfall from a volcanic eruption. Katmai National Park is home to more than a dozen active volcanoes; the world’s most powerful eruption of the 20th century occurred at Novarupta, just 23 miles from the archaeological district. In 1912, the massive Novarupta event and subsequent ashfall led to the abandonment of two nearby Alutiiq/Sugpiaq villages, and buried the Brooks Camp area, including the archaeological district, under eight inches of ash. Analysis of ash deposits from earlier eruptions suggests volcanic activity could explain why humans seem to have avoided the Brooks River area for centuries at a time.

Today, members of the Alutiiq/Sugpiaq people, descendants of villagers displaced by the Novarupta eruption of 1912, retain traditional fishing rights for portions of the lower river. The Alutiiq placename for the area, Qit’rwik, means “a sheltered place behind a point,” and reflects the millennia-old appeal of making a home here, despite the occasional threat of volcanoes and bears.

Related Tags

Know Before You Go

Rangers lead daily, hour-long tours to the reconstructed pit house from early June through mid-September. Check the visitor center for the exact time. It’s also possible to do a self-guided tour by signing out a key from the visitor center.

The forested, quarter-mile trail leading to the pit house is popular with bears, particularly those looking to nap undisturbed after feeding. Extreme caution and good bear etiquette must be practiced—everyone arriving at Brooks Camp attends a session reviewing appropriate behavior. There are no roads to the archaeological district, or to Brooks Camp itself; visitors arrive by float plane or water taxi, usually from the town of King Salmon, about 30 miles to the west.

Community Contributors

Added By

Published

September 16, 2022