About

In 1883, when three Canadian Pacific Railway workers stumbled onto the warm, mineral-filled waters in a cave nestled in Sulphur Mountain in Banff, they couldn’t have guessed that their discovery would lead to Canada’s first national park. But just a few years later, that's what it would become.

Although it’s true that those three workers—brothers William and Tom McCardell and Frank McCabe—did first see the waters for themselves in 1883, First Nations people had been enjoying the hot springs well before then; the Bow Valley, where the cave sits, has a record of human inhabitants dating back 10,000 years. But the McCardells and McCabe saw two things when they saw those steamy waters: money and potential. They built a fence around the cave and a cabin near its entry, and petitioned the Canadian government for ownership of the land, hoping to cash in on the ever-growing spa fad that had been sweeping through Europe. Bathers claimed that soaking in mineral-rich waters would, as researcher Katharine Fletcher writes, “treat everything from infertility to rheumatism and paralysis.” But they weren’t the only ones who saw the potential.

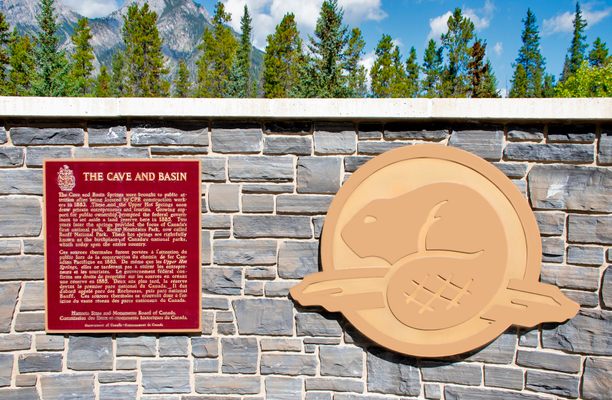

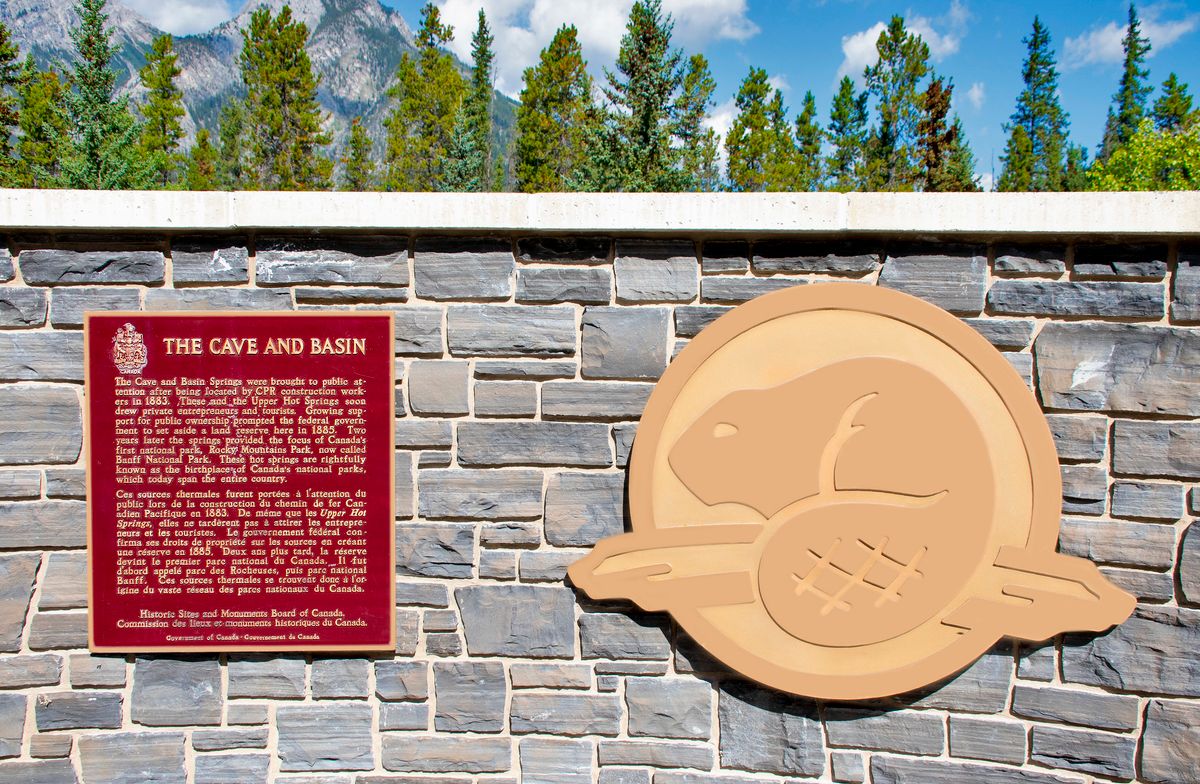

The Canadian government needed to finance the railroad and the revenue the springs could generate would be just the thing to do it. In a complicated story of competing lawsuits, in 1885, the site eventually became Hot Springs Reserve, with an order stating that the land was “reserved from sale or settlement or squatting.” By 1887, the boundaries of the reserve had expanded to nearly 300 square miles, and the area was renamed Rocky Mountains National Park, the first of its kind in the nation. The National Parks Act of 1930 saw another name change, with the park officially becoming Banff National Park.

Throughout the history of the land, one thing has been clear—people love those waters. The bright blue waters that lured the railroad workers still have their charm. The water comes from Sulphur Mountain, flowing into cracks in the rock, pulled deeper and deeper by gravity some two miles below. Heated by the Earth’s core, the water then pushes its way back up to the surface forming these thermal pools. The minerals in the water are a haven for wildlife, including fish, orchids, and a rare and endangered snail only found in the area.

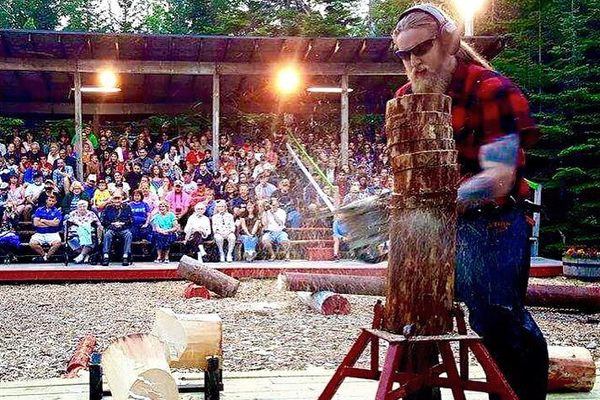

Though the Cave and Basin National Historic Site is best known for its namesake cave and basin, other activities at the site including hiking, cave, boardwalks, and historical tours. An adjacent prisoner of war exhibit educates visitors about another piece of Banff National Park's history—Canada's World War I internment camps.

Related Tags

Know Before You Go

Starting in June 2021, the Cave and Basin National Historic Site began offering modified access and services while maintaining physical distancing measures. Check the Parks Canada website for the most up-to-date information.

Community Contributors

Added By

Published

September 5, 2021