About

Rivers have frequently made convenient borders between neighboring groups. But what happens when years and years of erosion and shifting weather patterns cause a river to change its course? What happens when someone builds a dam or irrigation controls that alter the river's path? It had been a nearly universally-practiced convention that with the gradual and natural changes to a river over the course of many years, the boundary also gradually moves, but that sudden or man-made alterations would not change the location of a border. But what happens when both happen at the same time?

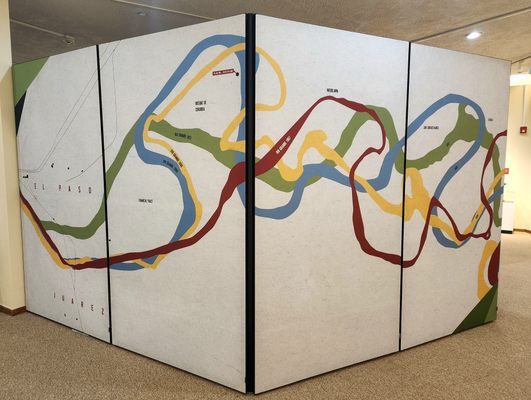

Along one section of the United States-Mexico border, between the cities of El Paso, Texas, and Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, both methods of altering the path of the river occurred simultaneously over many decades, eventually resulting in a confusing and diplomatic mess to determine where the border between the countries laid.

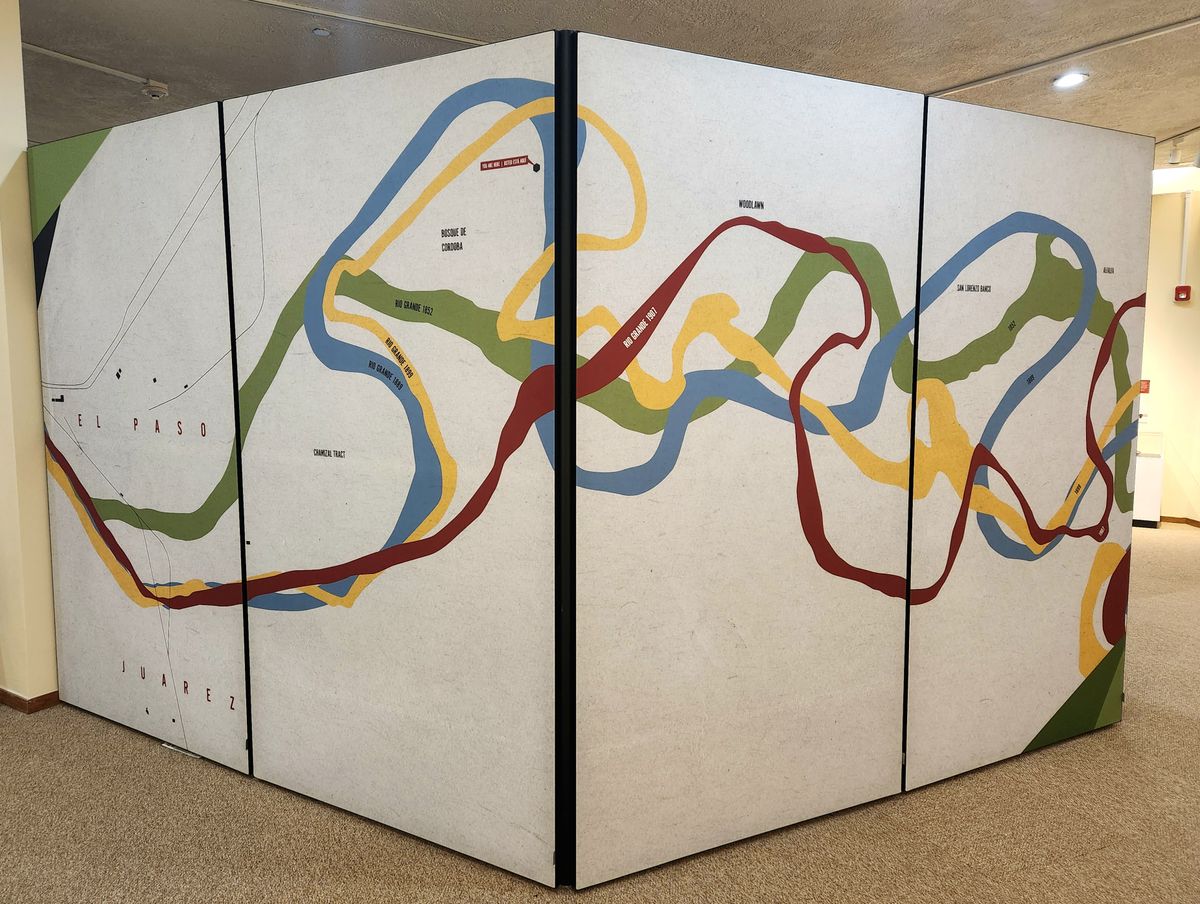

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848 that ended the Mexican-American War established much of the border between the countries at the deepest point along the Rio Grande. In the following decades, the river was surveyed as shifting south, mostly gradually but with one dramatic change after a flood in 1864. By 1873, the river had moved so far south that nearly 600 acres that had once been Mexico could arguably be inside the borders of the United States. Texans named this parcel of land "El Chamizal" and began settling there, although both countries claimed the land and lawsuits were filed in the courts of both countries. In 1899, both nations dug channels near the river's path in an effort at flood control. As this was an artificial change to the river's path, it was regarded as not moving the border, but did have the effect of placing an “island” of Mexican land inside the United States.

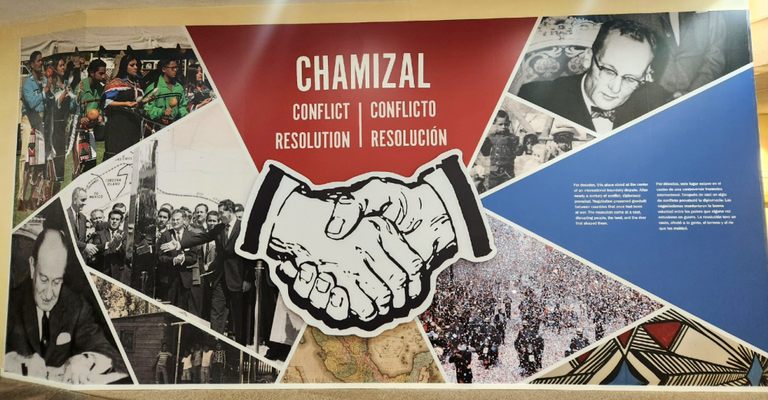

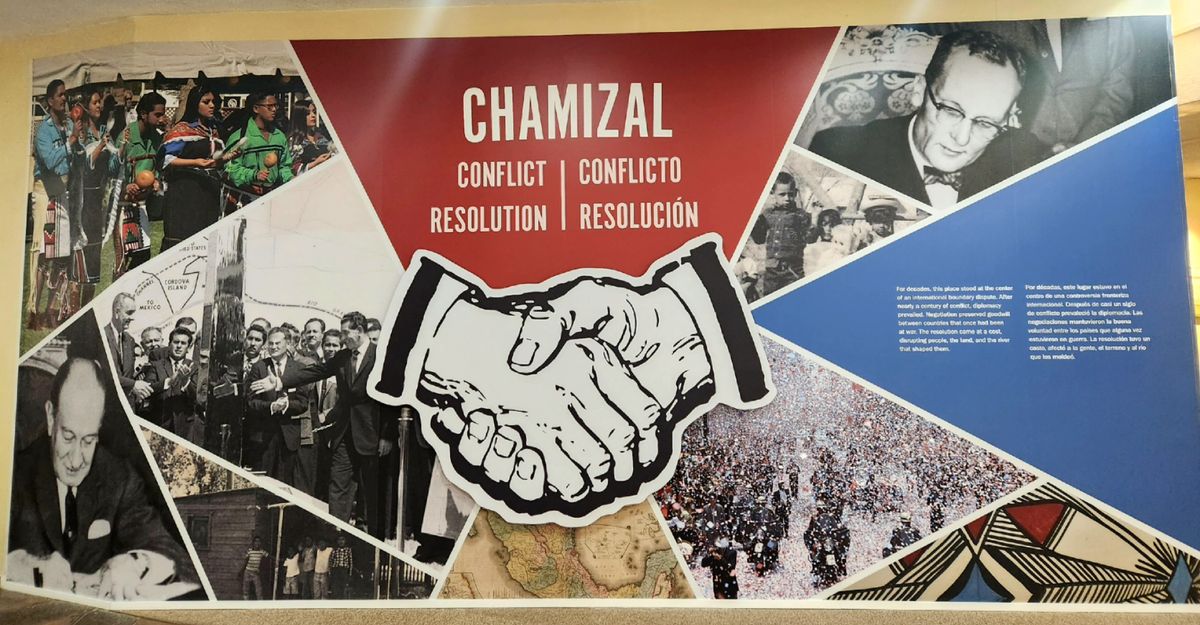

By the early 1900s, the murky border situation became enough of a diplomatic headache that the presidents of both nations agreed to meet and attempt to come to a settlement. In 1911, a commission recommended a new border be formally established after investigating where and how each section of the river had moved over the decades, but the United States rejected the commission's findings and the dispute continued for many more years, getting worse each year as the river continued to shift and more settlers from both nations moved into disputed territory. There were more proposals aimed at resolving the dispute, including the United States offering to assume Mexican debts or buy the disputed land outright, but none of these made it very far. The Chamizal issue became a stubborn point of pride for both nations.

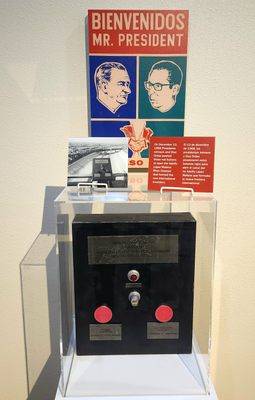

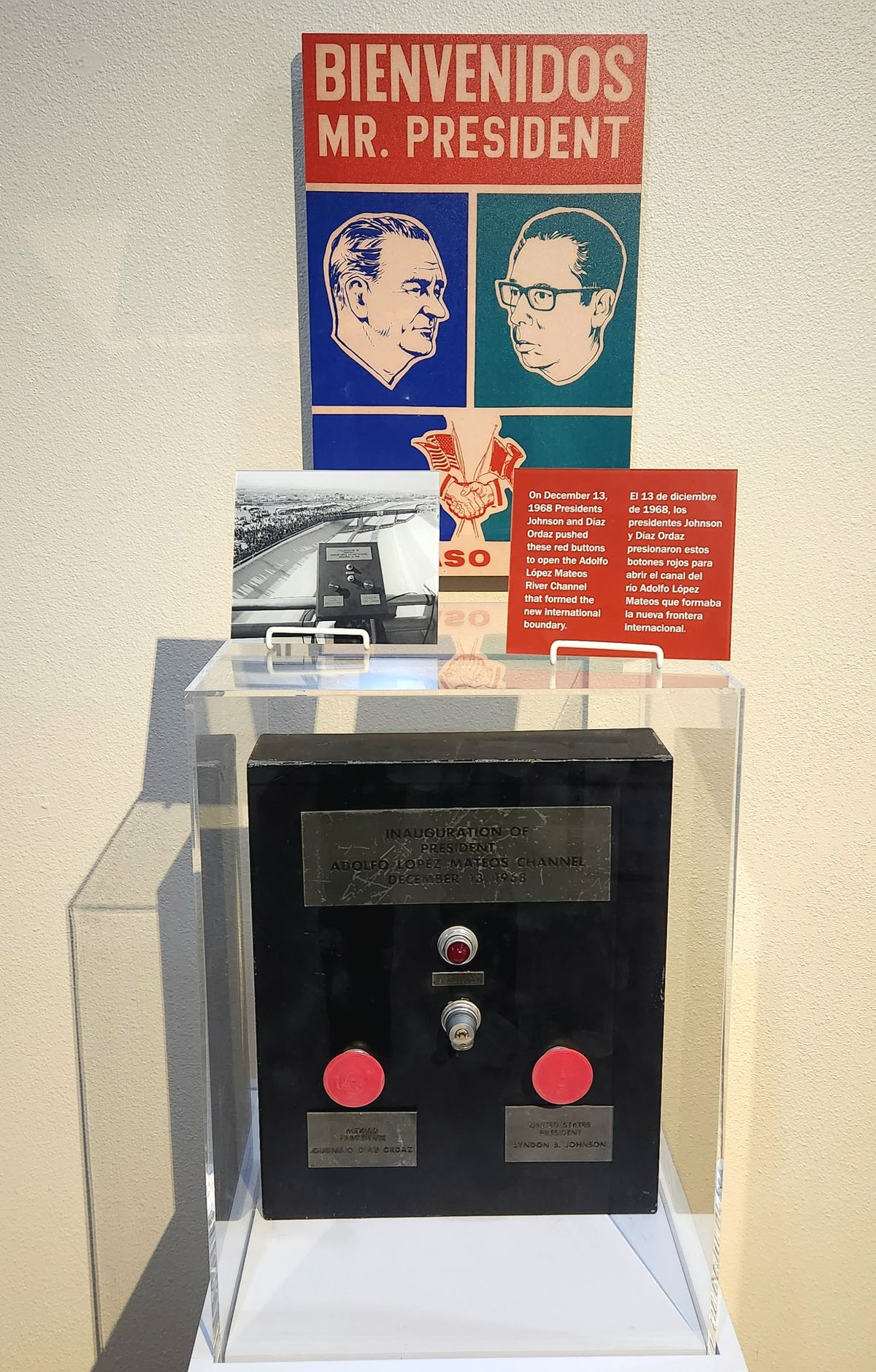

Finally, in 1963, President John F. Kennedy sent word to Mexico that the United States would be willing to accept the 1911 commission's findings. Unfortunately, he was assassinated before it could be formalized, but his successor, Lyndon B. Johnson, followed through on the commitment. Over 400 of the disputed acres were formally recognized to belong to Mexico and nearly 200 acres were recognized to belong to the United States. Both nations agreed to split the costs of creating a concrete channel for the river through the disputed area to prevent it from shifting any further. Nearly 5,600 Americans were required to move when the land they lived on was determined to be Mexican territory (they were compensated for their lost property).

In 1967, the presidents of the U.S. and Mexico met at the disputed border and shook hands in a ceremony celebrating the diplomatic resolution to the dispute. In 1974 the United States established the Chamizal National Memorial on some of the formerly disputed land. A museum in the memorial celebrates the peaceful resolution of the Chamizal conflict and the shared cultural values between the United States and Mexico.

Related Tags

Know Before You Go

Chamizal National Memorial is free to visit and open daily, except for Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Years Day.

Published

January 19, 2023