About

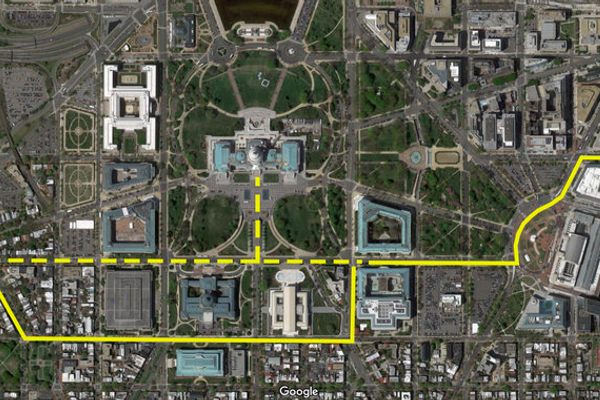

All across Washington, D.C. a polka dot trail of cavernous holes pierces the landscape. These shafts are only the tip of the iceberg on one of the city’s largest infrastructure efforts: An 18-mile-long sanitary subway called the Clean Rivers Project that aims to do for the Potomac what the “Back2Good” rehab did for the city's Metro system.

Washington is one of about 700 cities in the United States sitting on an aging set of combined sewage overflow (CSO) tunnels. CSO’s were the 18th and 19th-century version of the sewer "release valve" that diverts toxic wastewater into the river when treatment facilities are overwhelmed by heavy rains.

The Environmental Protection Agency policy has warned against CSO systems since 1994, casting the design as a public health threat and major contributor to pollution. Modern practices separate sewage and rainwater to ensure surging storms never come between the flush of your toilet and the scrubber plants at the other end of the line.

To remedy the problem, D.C. Water launched their ambitious Clean Rivers project in 2005. The plan is for the sanitation system to carry an underground river of poop out of the District, down to the largest water treatment plant in the world next to the sprawling Joint Base Anacostia-Bolling. Construction is presently underway with locomotive-sized tunnel boring machines that can chew through about 100 feet of clay per day.

Currently, the Blue Plains Wastewater Treatment Plant handles the waste generated by the two million people in the District-Maryland-Virginia area. When the new Clean River tunnels are complete in 2025, they expect to generate $10 million worth of electricity from the sewage by using thermal hydrolysis.

Related Tags

Community Contributors

Added By

Published

November 27, 2017