About

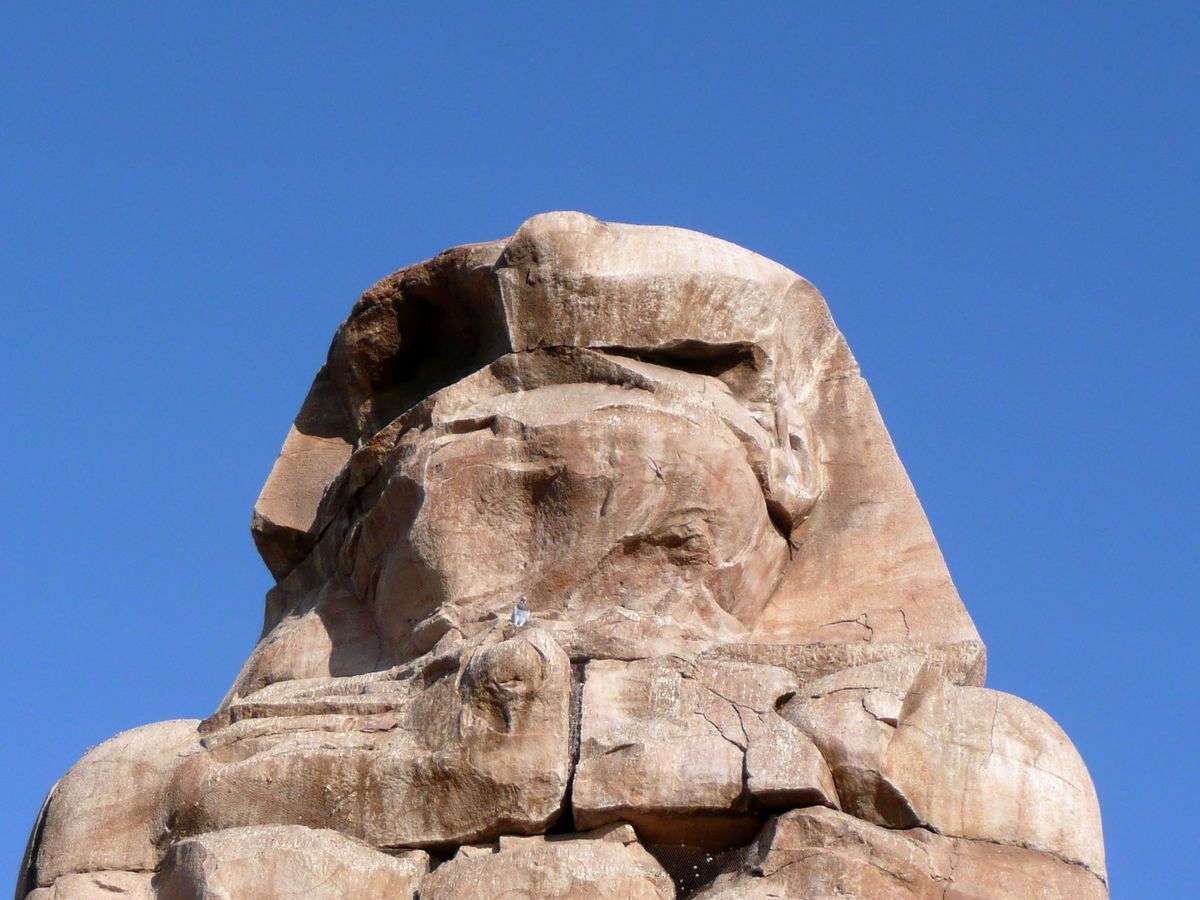

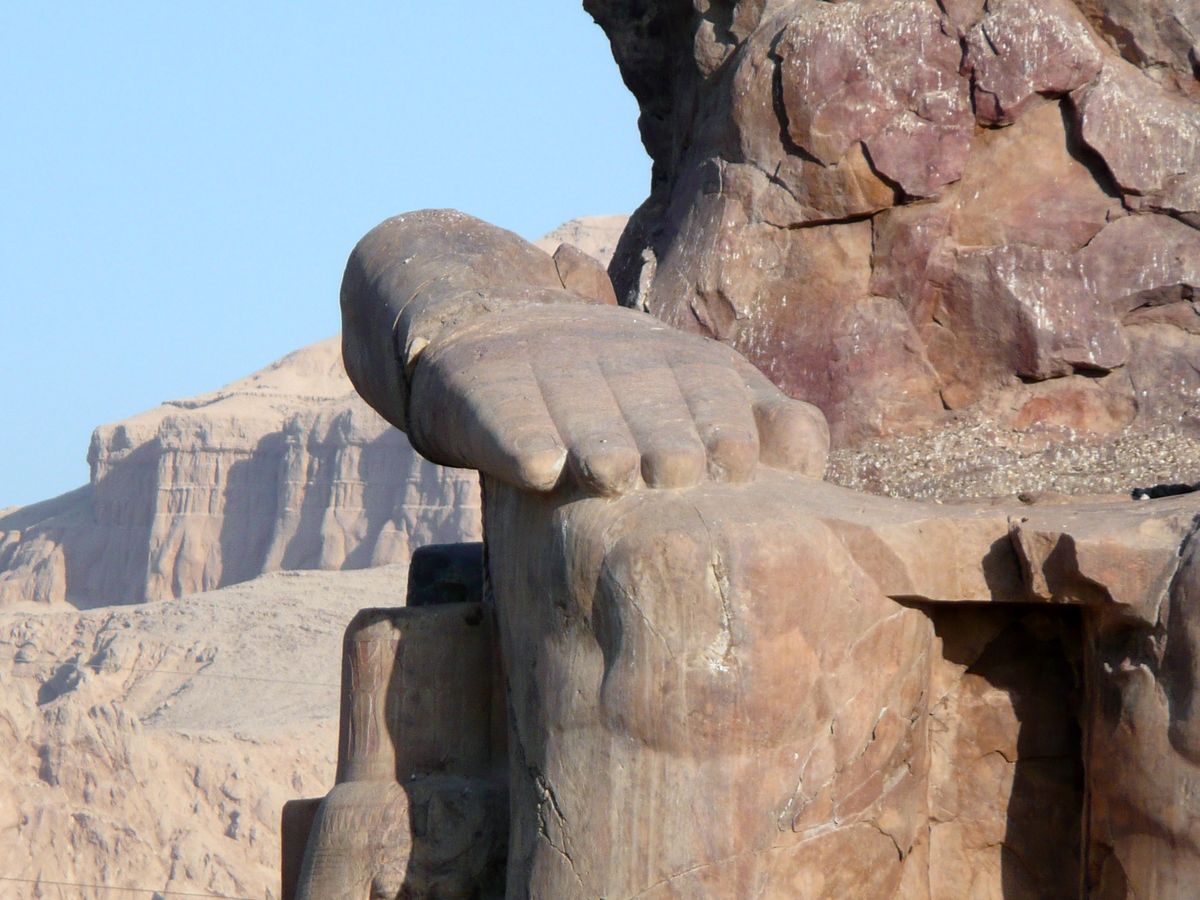

Since 1350 B.C., these ancient Egyptian statues have loomed over the Theban Necropolis. Though battered by more than 3,400 years of scorching desert sun and sporadic Nile floods, they’ve captivated the imaginations of curious travelers for millennia.

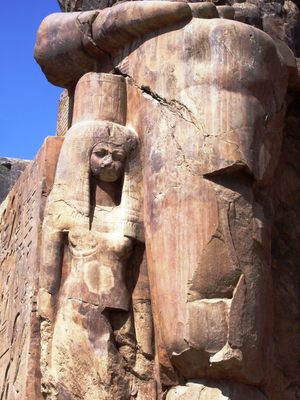

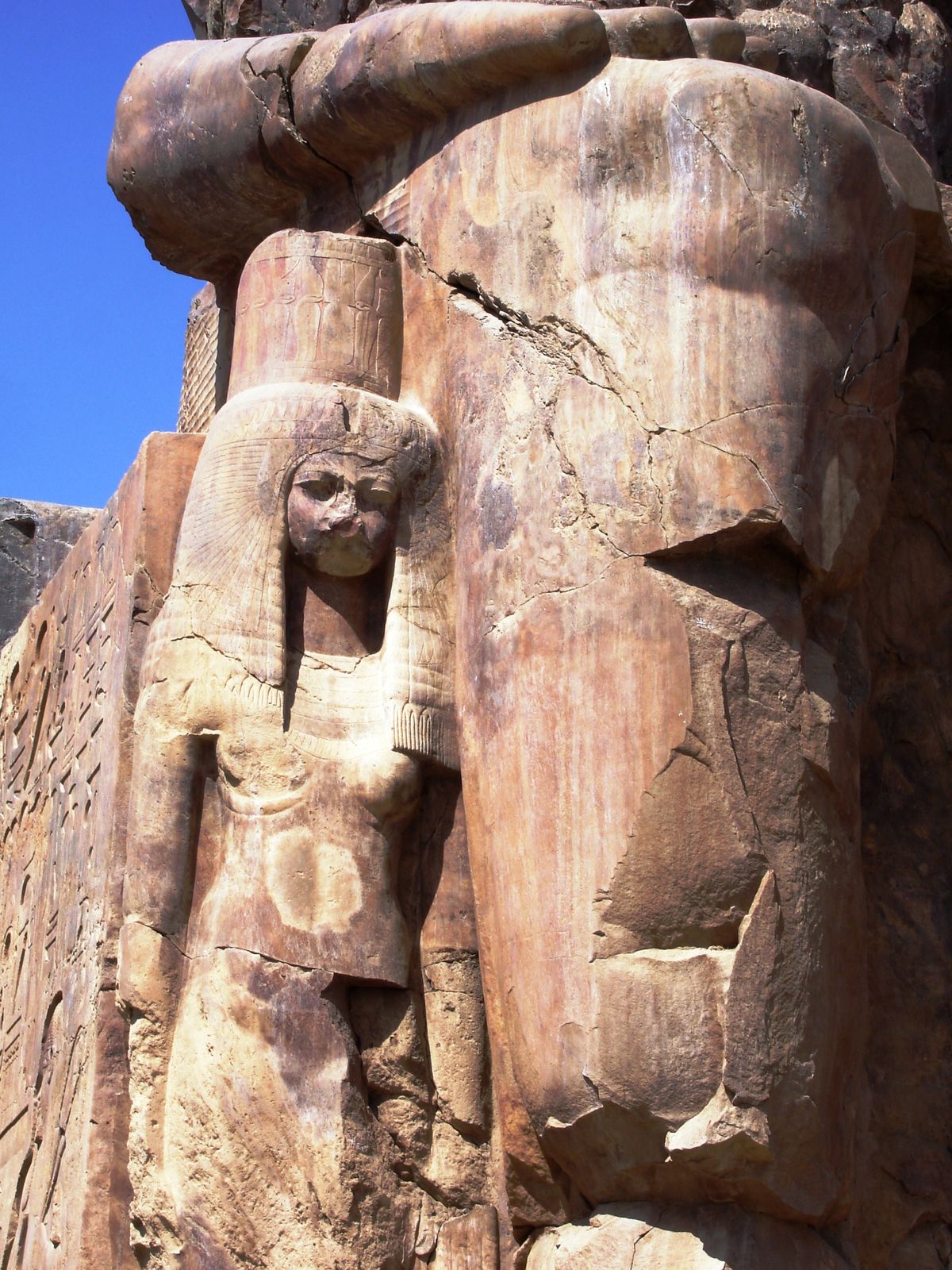

The twin colossi (which no longer resemble twins) depict the Pharaoh Amenhotep III, who ruled during the 18th Dynasty. They once flanked the entrance to his lost mortuary temple, which at its height was the most lavish temple in all of Egypt. Their faded side panels depict Hapy, god of the nearby Nile.

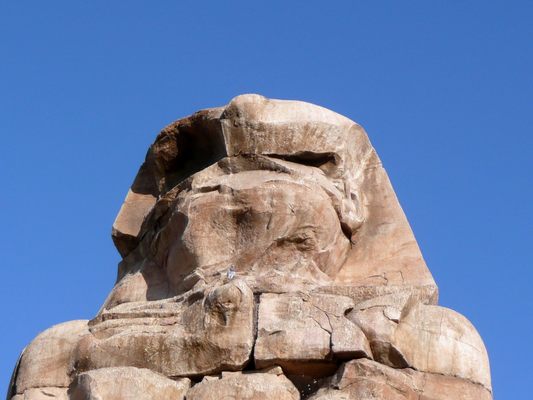

Though centuries of floods reduced the temple to no more than looted ruins, these statues have withstood any disaster nature throws their way. In 27 B.C., an earthquake shattered the northern colossus, collapsing its top and cracking its lower half. But strangely, the damaged statue did more than merely survive the catastrophe: After the earthquake, it also found its voice.

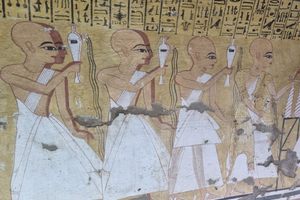

At dawn, when the first ray of desert sun spilled over the baked horizon, the shattered statue would sing. Its tune was more powerful than pleasant; a fleeting, otherworldly song that evoked mysterious thoughts of the divine. By 20 BC, esteemed tourists from around the Greco-Roman world were trekking across the desert to witness the sunrise acoustic spectacle. Scholars including the likes of Pausanias, Publius, and Strabo recounted tales of the statue’s strange sound ringing through the morning air. Some say it resembled striking brass, while others compared it to the snap of a breaking lyre string.

The unearthly song is how these ancient Egyptian statues wound up with a name borrowed from ancient Greece. According to Greek mythology, Memnon, a mortal son of Eos, the goddess of Dawn, was slain by Achilles. Supposedly, the eerie wail echoing from the cracked colossus’ chasm was him crying to his mother each morning. (Modern scientists believe early morning heat caused dew trapped within the statue’s crack to evaporate, creating a series of vibrations that echoed through the thin desert air.)

Sadly, well-intentioned Romans silenced the song in the third century. After visiting the storied statues and failing to hear their ephemeral sounds, Emperor Septimius Severus, reportedly attempting to gain favor with the oracular monument, had the fractured statue repaired. His reconstructions, in addition to disfiguring the statue so the fixtures no longer looked like identical twins, robbed the colossus of its famous voice and rendered its song a lost acoustic wonder of the ancient world.

Related Tags

Know Before You Go

For the past couple of decades, a full excavation of the temple site has been undertaken, and still continues — note the white fence in the distance beyond the colossi, which serves to keep visitors from accidentally falling into excavation trenches. The Colossi are also free to visit.

Treasures of Egypt: Hidden Tombs, Ancient Pyramids & Old Cairo

Explore pyramids, tombs, and local cuisine with your Egyptologist guide.

Book NowCommunity Contributors

Added By

Published

March 7, 2018

Sources

- https://theworldtravelguy.com/colossi-of-memnon-giant-statues-in-luxor-egypt/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Colossi_of_Memnon#Sounds

- http://anthropology.msu.edu/anp455-fs14/2014/09/11/colossi-of-memnon/

- https://science.howstuffworks.com/science-vs-myth/unexplained-phenomena/colossi-memnon-sing-at-sunrise.htm

- https://www.lonelyplanet.com/egypt/luxor/attractions/colossi-of-memnon/a/poi-sig/1426487/355253