About

Henry Chapman Mercer, a renowned archaeologist, tile maker, and collector of Pennsylvanian pre-industrial household utensils wrote of his home, Fonthill:

"The house was planned by me, room by room, entirely, from the interior, the exterior not being considered until all the rooms had been imagined and sketched, after which blocks of clay representing the rooms were piled on a table, set together and modeled into a general outline. After a good many changes in the profile of the tower, roofs, etc., a plaster of Paris model was made to scale, and used until the building was completed."

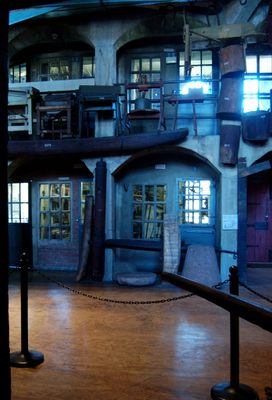

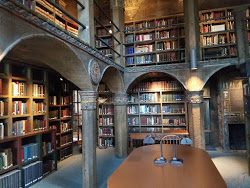

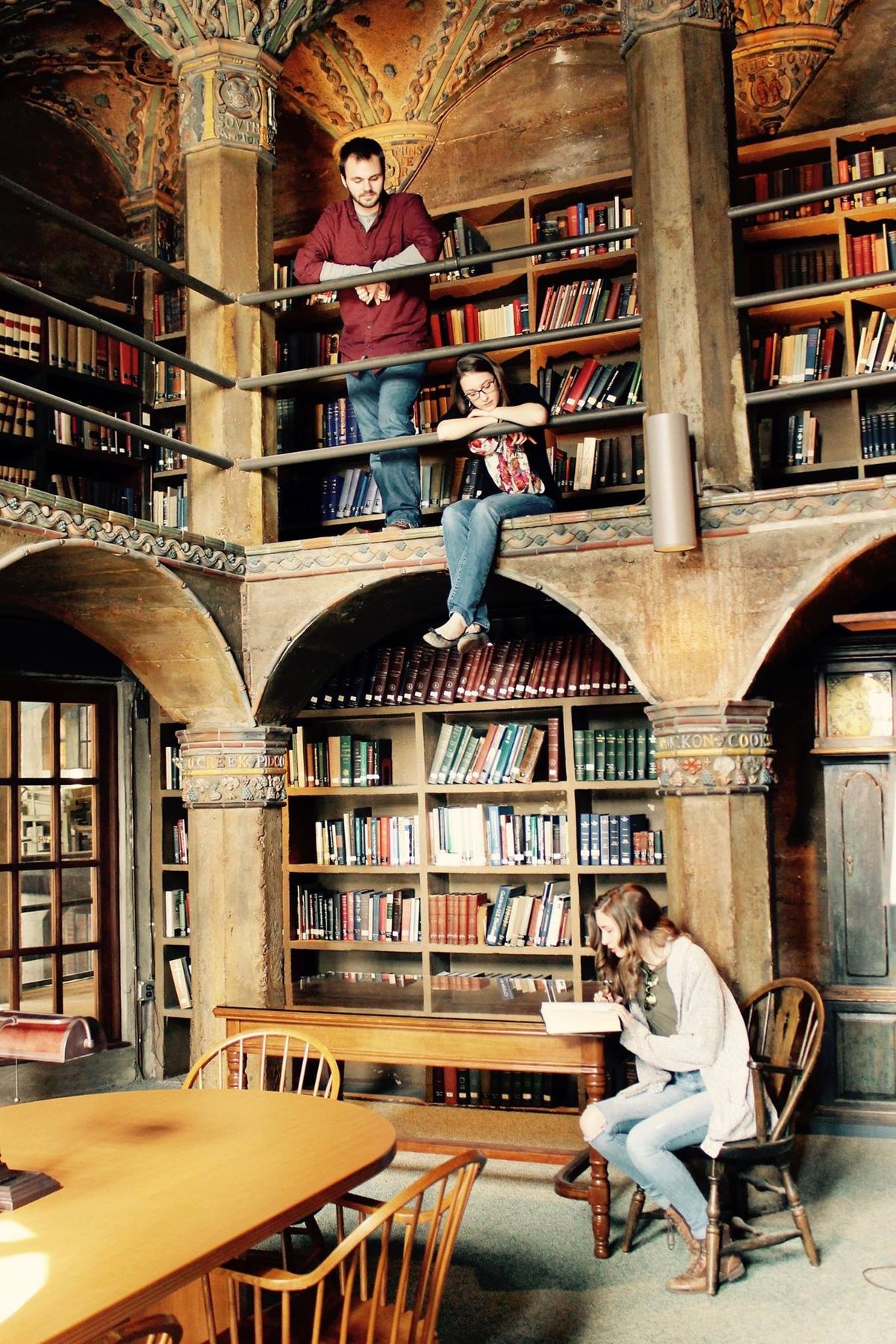

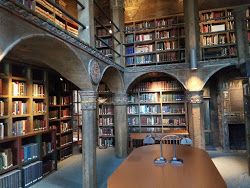

Finished to Mercer’s exact specifications in 1912, Fonthill remains an ornate, architecturally unclassifiable mansion constructed entirely out of poured concrete.

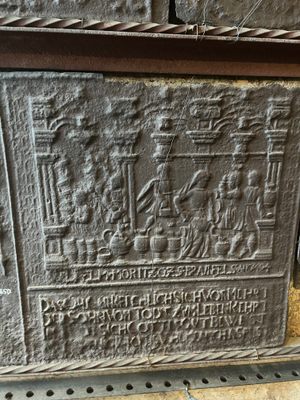

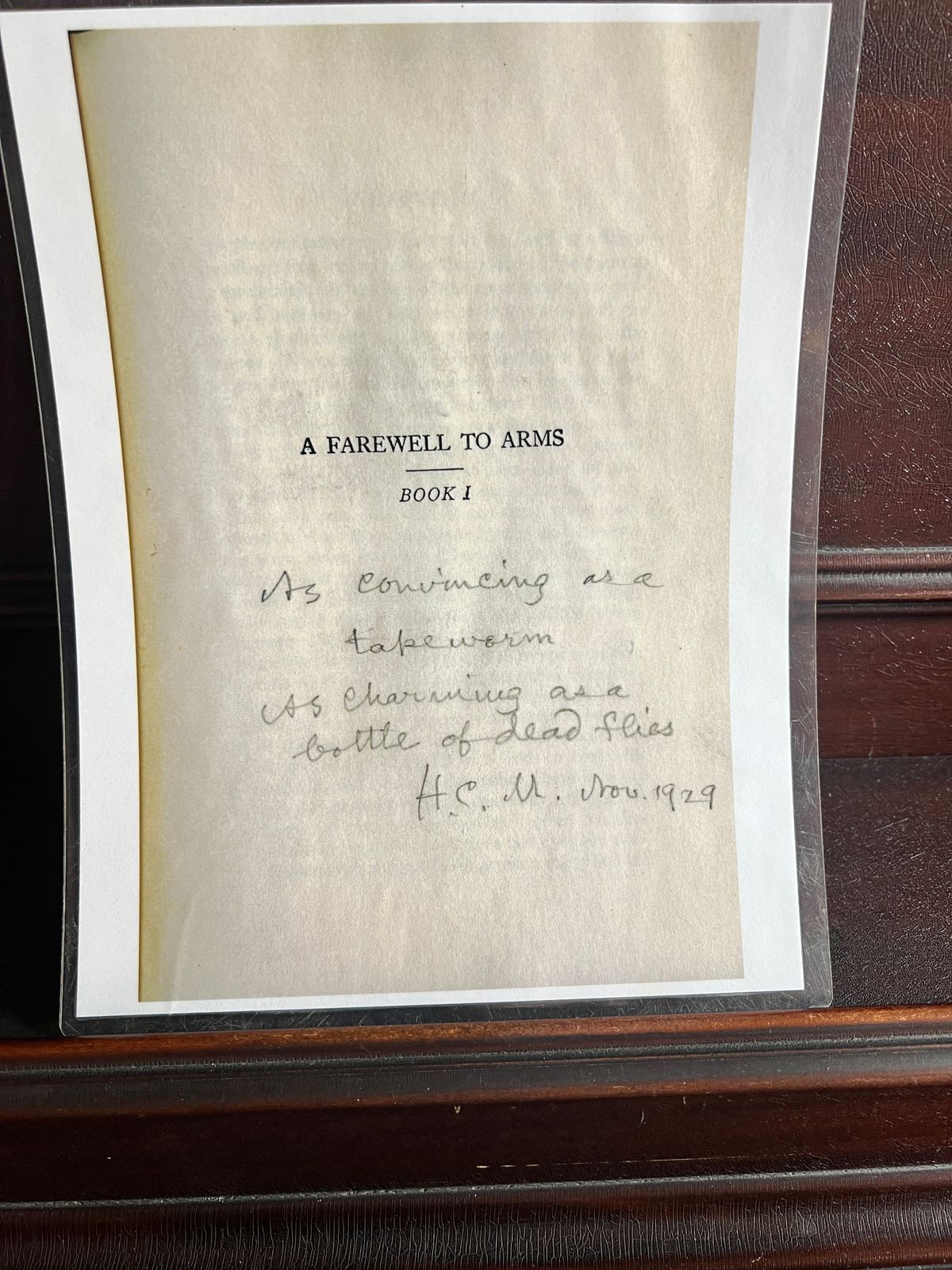

Besides being an archaeologist, Mercer was a self styled anthropologist, ethnographer, and perhaps most importantly, collector. When Mercer began to collect artifacts for his museum, his aunt informed him that she had a vast collection of medieval armor. Mercer was delighted, as he wanted the Mercer Museum to contain not only relics of American history, but world history as well. The armor was kept in storage in Boston while Mercer continued to collect. But the storage building was made of wood, in the year 1872, the Great Boston Fire destroyed much of the city, and all of Mercer’s armor.

Devastated, Mercer realized that he could not risk fire erasing his collected Americana before future generations could learn from them, and concrete was his answer. The people of Doylestown thought he was crazy, spending years immersed in building his concrete castles, but Mercer had the last -- possibly crazed -- laugh when, years later at the completion of Fonthill, he climbed to the very top terrace and built a huge bonfire, high enough for all of Doylestown to see. Fireproof.

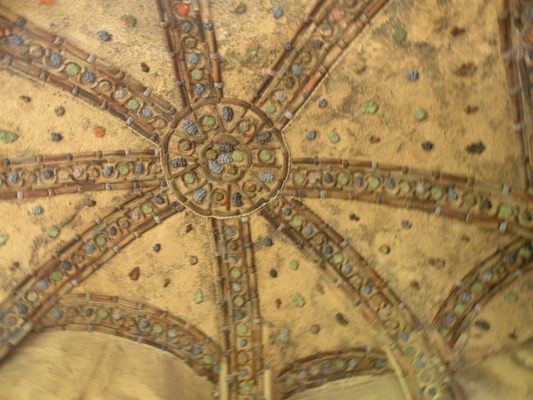

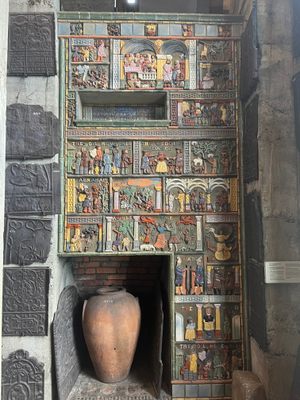

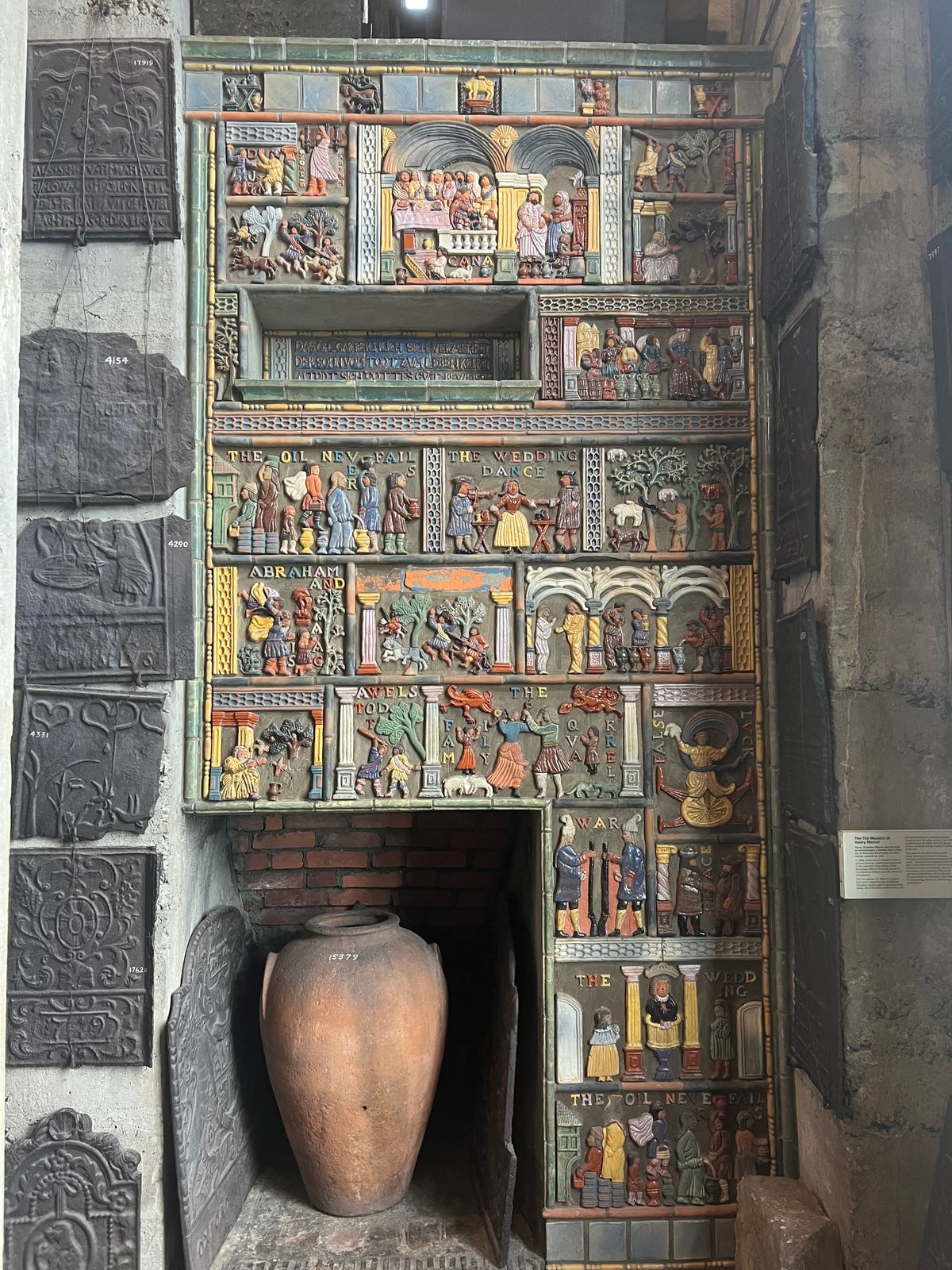

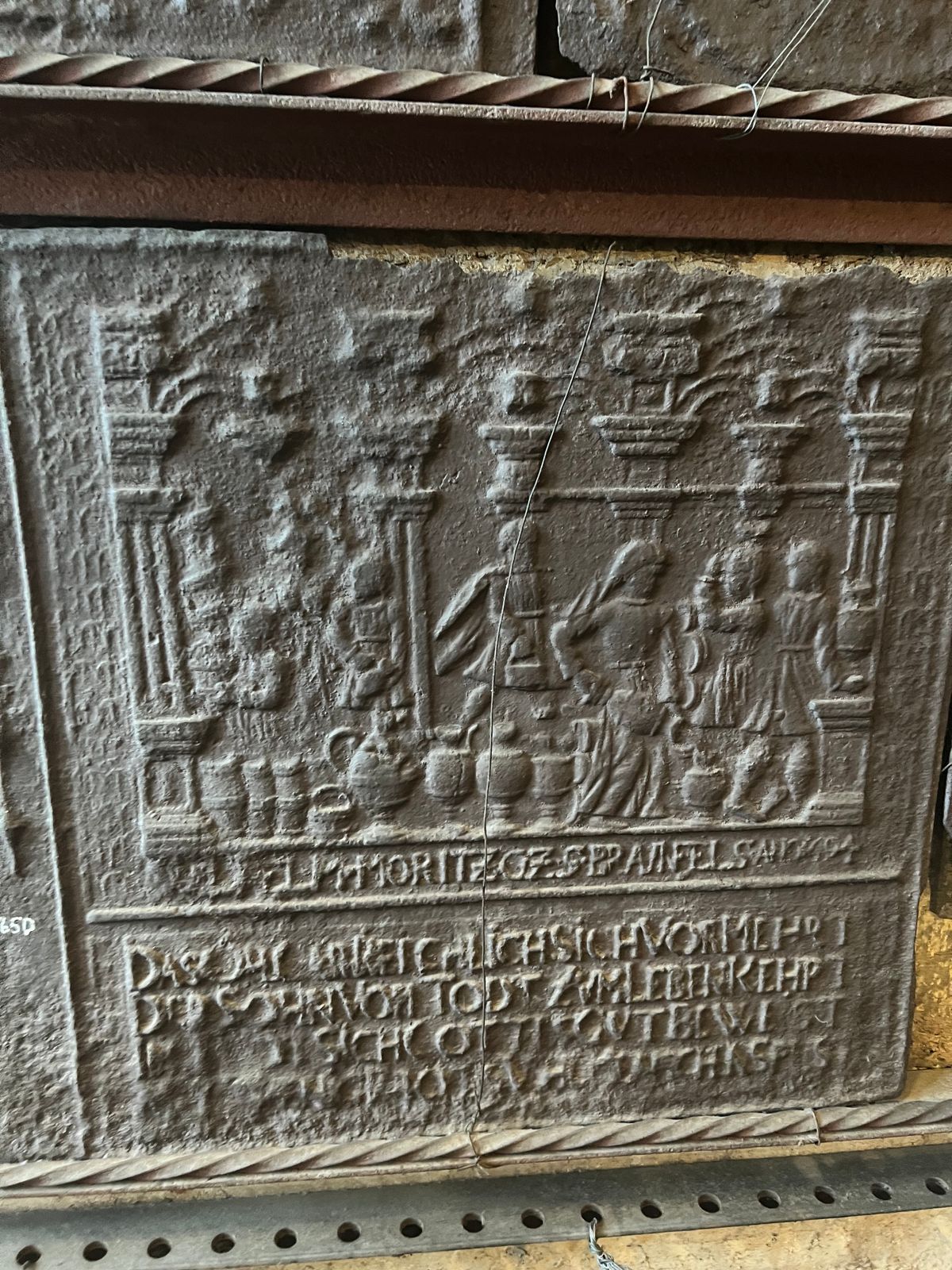

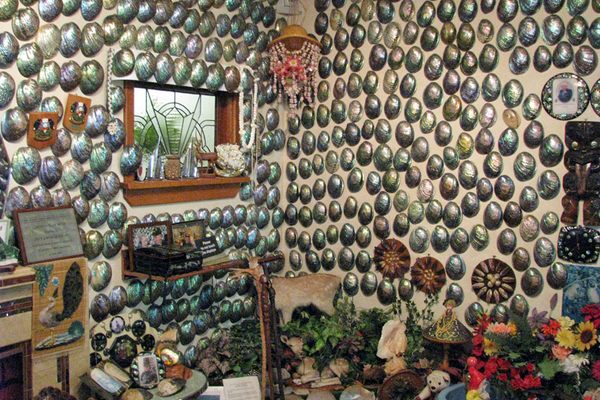

Today Fonthill displays evidence, both inside and out, of a reason to Mercer’s madness (including a professed "unbending hostility to ugliness and false taste"), although the architectural rhyme and reason—dormer placement and roof pitch, 32 staircases balanced by only eight bedrooms—are only fully understood by Mercer himself. Ornamentally the same holds true: vaulted ceilings are decorated with glittering inlaid tiles taken from Mercer's factory and personal ceramics collection, despite the walls remaining untouched by paint.

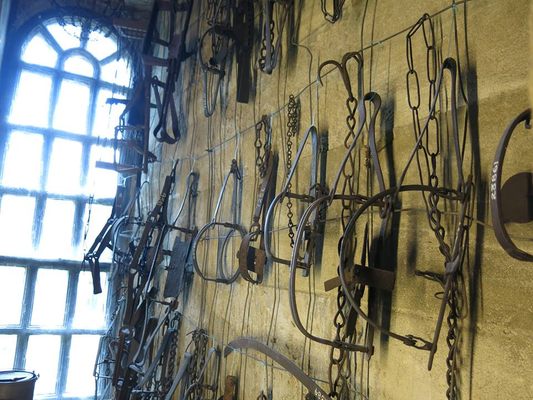

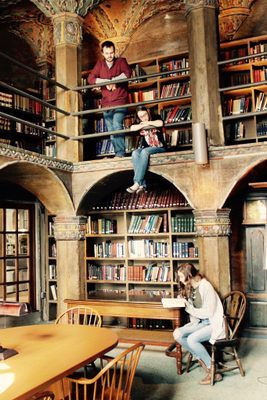

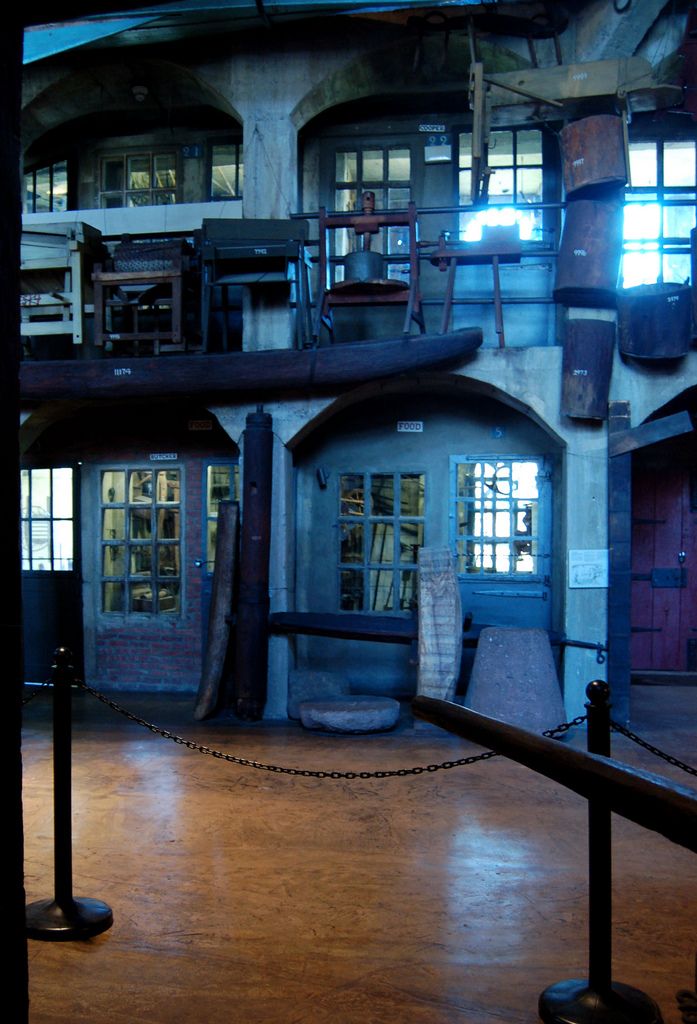

Among Mercer's collection held at the Mercer Museum (located close to but separate from Fonthill), are the everyday tools and things of the average American in the 18th and 19th centuries, from a watchmaker’s gears, to the wares in a tortoiseshell comb maker's shop, butcher’s instruments, even a whaler’s boat. Keep your eyes out for the fake, but neat looking, vampire hunting kit.

The often mentioned haunting of Fonthill’s woods adds a bit of paranormal flair to an already eccentric establishment, though Mercer no doubt would have found it gauche to have the former housekeeper terrorizing his evening guests.

Related Tags

Community Contributors

Published

October 21, 2009