About

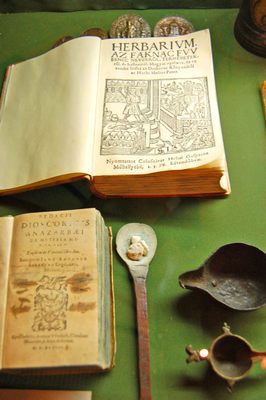

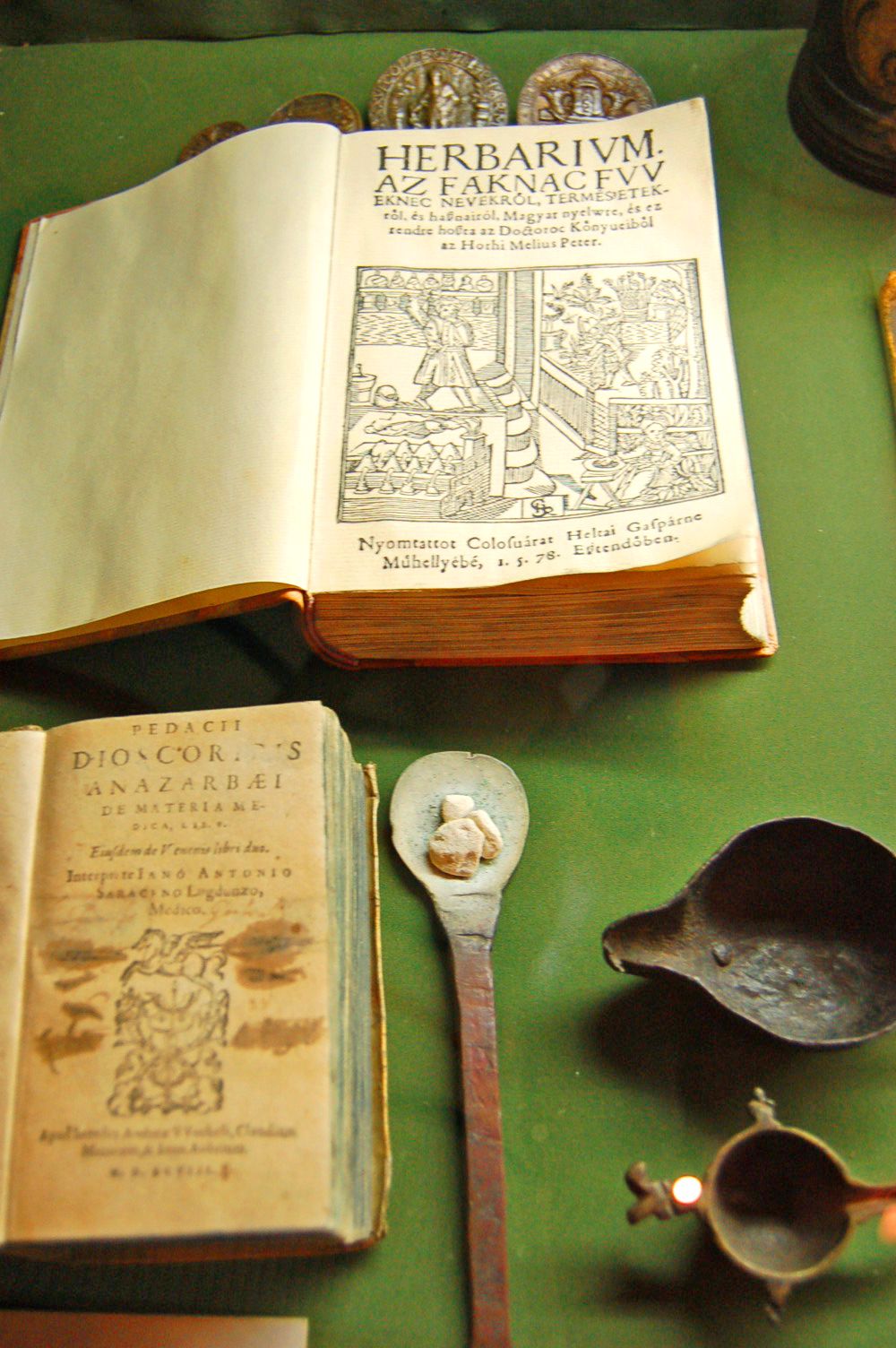

What began as a private collection of pharmaceutical oddities in 1896 became a museum in 1948. Called a collection of “Historical Chemist Relics,” it is better described as an alchemy museum.

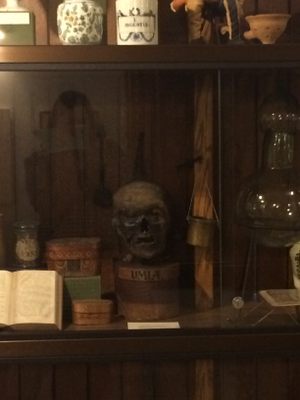

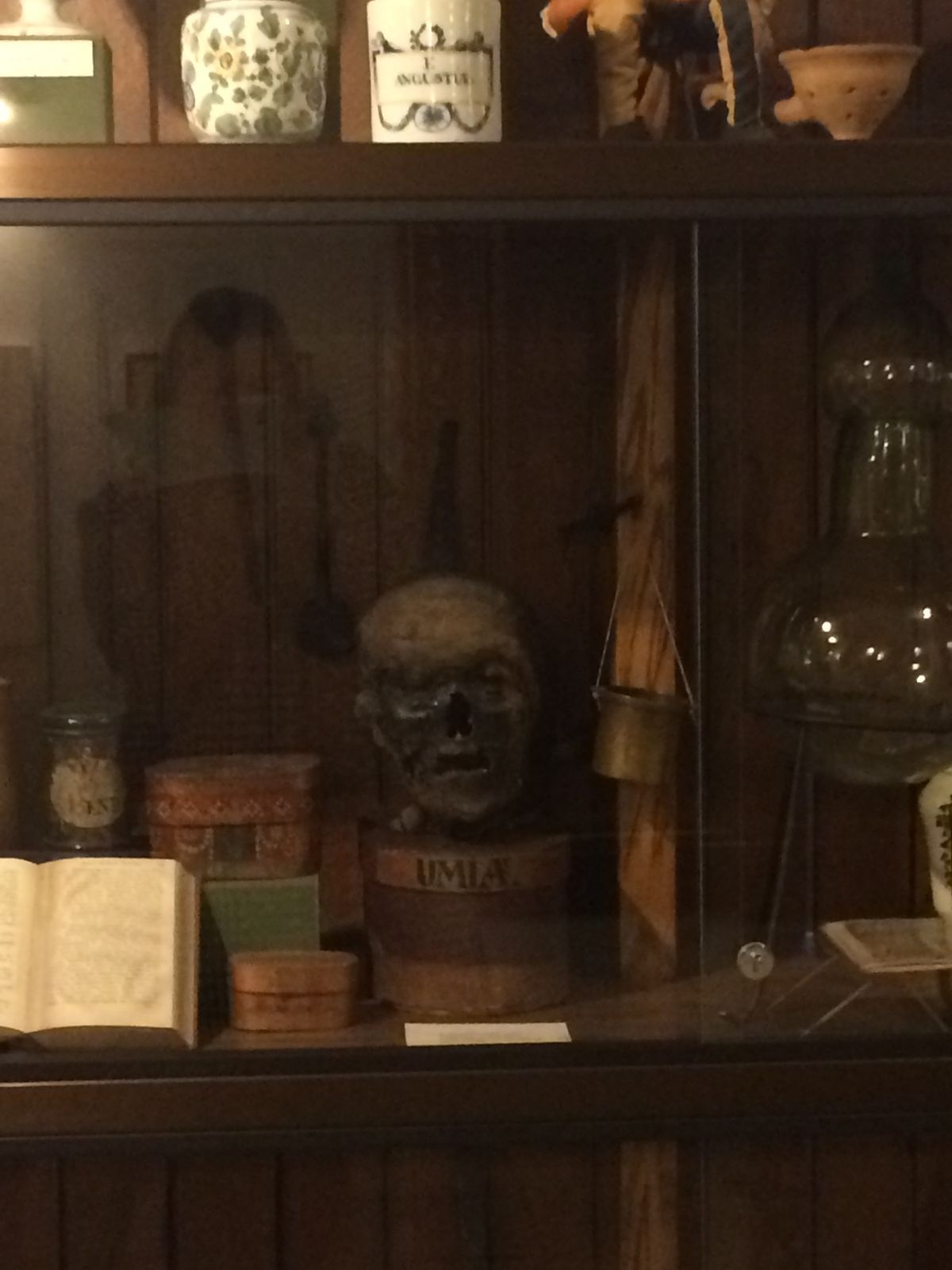

Among the curious items in this small museum is a bottle of Ambra Grisea Malac (Ambergris, or Sperm Whale vomit), for use on “Lean, thin, emaciated persons who take cold easily” and those who “with great sadness, sit for days weeping.” Besides the hanging bats, lizards and crocodiles, worth looking for is the box of mumia or mummy powder. Easily spotted by the decaying head on top, it is what it sounds like: the powder is made of ground-up mummies meant to be eaten or applied as a salve. All of which was the result of a poor translation.

The Arabs were very fond of using Bitumen (a tar like substance) in their medicine. It bubbled up from the ground in the mountains of Persia and was an excellent way to staunch wounds. They called this stuff mumia. After the Arabs invaded Egypt, they also began calling those cloth wrapped bodies the Ancient Egyptians left laying everywhere mumia as well. They thought the bodies were prepared with bitumen, like the Greeks and Romans embalmed their dead (in fact they weren't; the Egyptian mummies were prepared with a natural salt.)

In the twelfth century, aided by the crusades, and a poor translation by Gerard of Cremona, it was decided that bitumen and mumia were one and the same. The black stuff came from mummies, and mummies were prepared in the black stuff, so you could use one for the other.

By the 1400s the mummy trade was in full effect. Mummy powder was being used for everything from epilepsy to upset stomaches. Of course, mummies are rather hard to come by. The entire stock of thousands of mummies (likely the Guanche aristocracy) found on Canary Island was used up in a matter of years.

Merchants even began making new mummies to satisfy the demands. They would buy the recently deceased, stuff them full of herbs and leave them out to dry. By the 1600s mummies were big business and everyone who was anyone used it. Francis Bacon loved it, so did Francis I of France. Shakespeare wrote about it in Othello and Macbeth, while his son-in-law John Hall prescribed it to his ill patients.

The mummy trade eventually slowed mainly due to a tightening of Egyptian government on the practice, and the ever more difficult process of finding and smuggling authentic mummies. Mummy was still available in the catalog of Merck as late as 1908: “Genuine Egyptian mummy, as long as the supply lasts, 17 marks 50 per kilogram.” The jar of mumia at the Golden Eagle Pharmacy Museum is a rare little reminder of this past.

Related Tags

Community Contributors

Added By

Published

January 1, 2009