About

The decorative ingenuity of the Heigold House façade’s original owner and builder, Christian Heigold, has endured over 175 years of flooding and potential effacement by municipal waste. It still stands today as a testament to its owner's enduring belief in the American experiment.

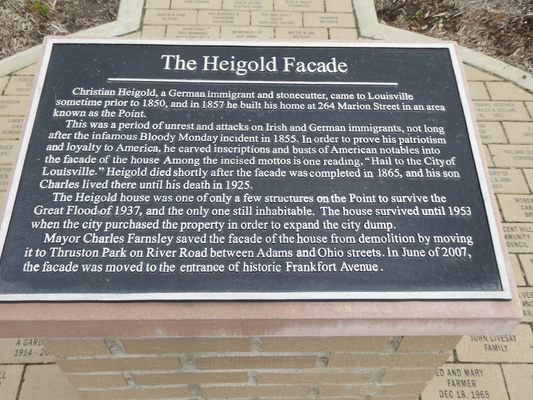

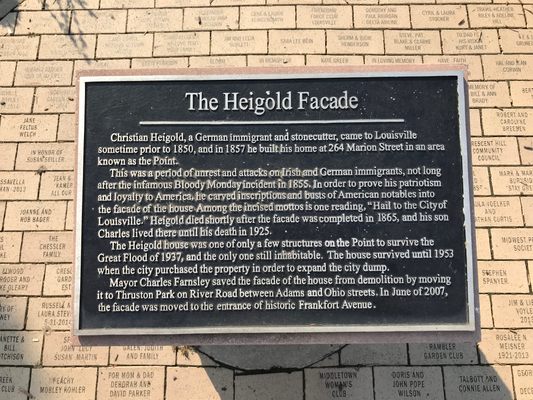

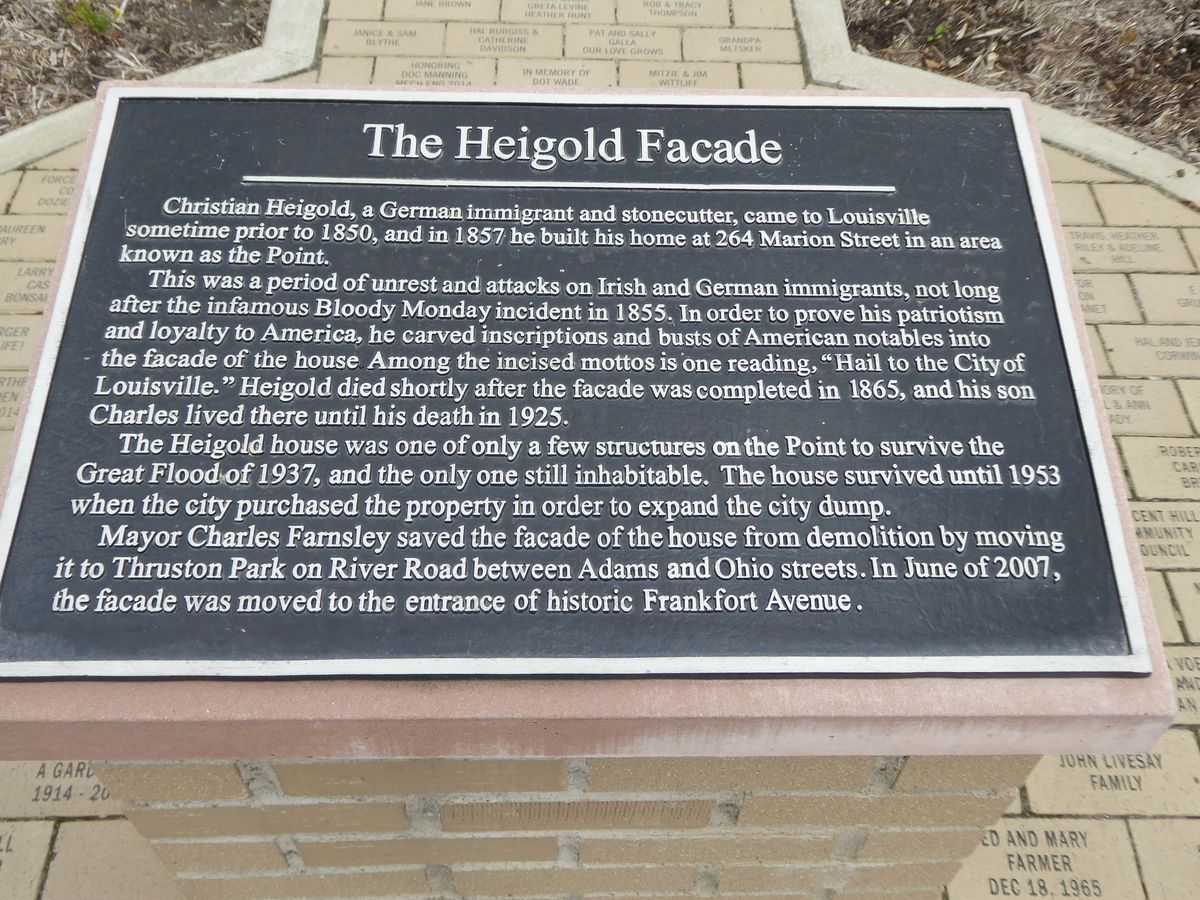

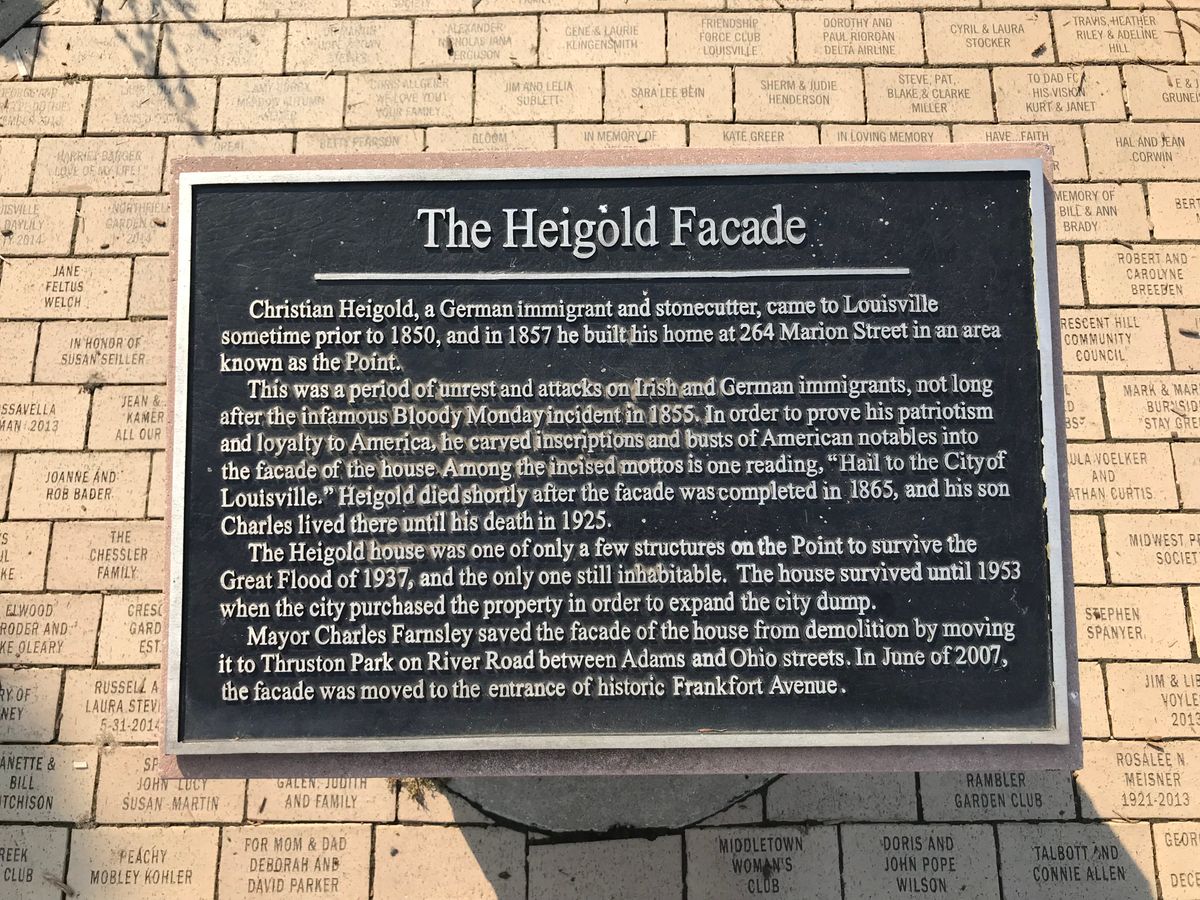

Christian H. Heigold was a successful stonecutter who immigrated to Louisville from Germany in 1850, settling in a thriving neighborhood called The Point along the Ohio River just east of downtown. The Point was located in the swath of land directly across River Road from where the façade now sits. At the time Heigold moved, The Point was populated by families who had moved to Louisville in the 1840s from New Orleans, whose mark was evidenced by a street in the neighborhood called “Frenchmens Row” despite the recent influx of affluent German and Irish immigrants.

Heigold quickly went about building his mansion, completing a majority of the house by 1853. While only a handful of his stone carvings have survived on the buildings façade, Heigold used his ample stonecutting skills to adorn his house with images of his family integrated into patriotic scenes, including busts of Presidents James Buchanan and George Washington. The façade is only a taste of his stonecutting skills; Heigold even cut the stone steps of the old Jefferson County Courthouse in Louisville.

Despite Heigold’s labors of American love, Louisville in the mid-nineteenth century was crucible of anti-immigrant sentiment. The editor of the Louisville Journal was a member of the xenophobic Know Nothing Party, and had been running a long editorial campaign against the German Catholic and Irish immigrants in Louisville. These tensions came to a head on August 8th, 1855 when a Protestant mob attacked over 100 predominantly Irish and German businesses and homes, killing 22 people. While no one was ever prosecuted for the violent riot, fittingly named Bloody Monday, those events left an indelible mark on the demographic make-up of Louisville and doubtlessly disrupted the sense of belonging Heigold felt in his new Kentucky home.

The patriotic scenes Heigold cut into his home are a way of publicly proclaiming his American identity amidst the rampant anti-immigrant sentiments. Even without the three-quarters of the original mansion, the façade abounds with details depicting Heigold’s American idealism. A bust of James Buchanan, President from 1857-1861, sits about a central window on the second floor. Buchanan was favored by Heigold as a portrait subject not only because he was then vying for the presidency, but Buchanan was also well known by immigrant populations for his work against the Know Nothing Party. Buchanan’s bust is flanked on either side by the words “Hail to Buchanan, Now and Forever,” and “The Union Forever. Hail to the Union Forever; Never Dissolve It.”

On the decorative lintel piece over the door, Heigold cut a scene depicting George Washington surrounded by a figures respectively called the Lady of Justice and the Lady of Culture with the words “Hail to the City of Louisville” directly above the entranceway. Despite a laborious construction, Christian Heigold was not able to enjoy his Louisville home for long. Heigold died in 1865, leaving the house to his son Charles. The passing of the elder Heigold marked the beginning of nearly a century and a half of unrest for the house and surrounding neighborhood.

A few months after the completion of the Heigold House, the city diverted the large Beargrass Creek away from downtown, cutting into The Point neighborhood. The city of Louisville began to move people out of the parts of The Point most effected by the move, though the newly diverted creek proved to be a serious flood hazard to an already low-lying river bank neighborhood. The Point was flooded almost annually, changing the socioeconomic character of the neighborhood, and the city provided increasingly less support for flood victims. The lack of municipal support was most pronounced in the wake of the Great Flood of 1937. The Point was demolished by the flood, and the city vowed to stop rebuilding and maintaining municipal services due to the constant flood issues.

By 1953, the city of Louisville began to buy and demolish properties in The Point to expand a dump site that had been encroaching on the neighborhood for a few years. The Point had virtually disappeared by then, demolished or covered in city waste, aside from the façade of the Heigold House, which had recently become listed on the National Registry of Historical Places.

By the 2000s the dump site was removed, but the Heigold House remained in the empty Thruston Park facing River Road. After a developer bought the adjacent land to the to build luxury condominiums in 2007, the 70,000-pound façade was carefully moved across River Road to its current location.

The story of the Heigold House is largely one of disavowal and acceptance into the greater history of the city of Louisville. Perhaps Christian Heigold would be pleased to know that the façade of his house is highly visible and central to a new, public Louisville waterfront. Close to the newly revamped Big Four Pedestrian Bridge and Waterfront Park, and marking the entrance of the Louisville Waterfront Botanical Gardens, the Heigold House is centrally located in the reclaimed waterfront plan. To paraphrase the words of famous Louisvillian Hunter S. Thompson, the Heigold House has remained a symbol of Louisville’s history because it is too rare to die.

Related Tags

Know Before You Go

Public Parking is available for the Heigold House about a half-mile west of the site itself, just down River Road towards downtown Louisville. There are two prominently marked public parking lots available on either the north (closest to the Ohio River) or south side of River Road. There are sidewalks along either side of River Road making for easy pedestrian access. Close viewing of the facade is not strictly handicap accessible, as the facade and surrounding gardens are set up on a curb, but there is a part of the roundabout that cars are not supposed to pass through that is accessible and allows for some fairly detailed views. The parking lots are on the eastern edge of Waterfront Park, so if the weather is amenable, you can stroll across the Ohio River on the handicap accessible Big Four Pedestrian Bridge, or check out the other features of Waterfront Park.

Community Contributors

Added By

Published

August 17, 2016

Sources

- http://brokensidewalk.com/2015/heigold-house-history/

- Domine, David. “Written in Stone: German-born Christian Heigold was a Patriot who Carved his Love for America in Stone,” in German Life, Issue 7 Number 3, November 30, 2000. 32-34.

- http://historiclouisville.weebly.com/the-point.html

- http://louisvilleky.com/louisville-uncovered-presents-the-heigold-house-mystery-behind-the-facade-on-river-road/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bloody_Monday

- https://practicalwanderlust.com/things-to-do-in-louisville-kentucky/

- Google Earth