About

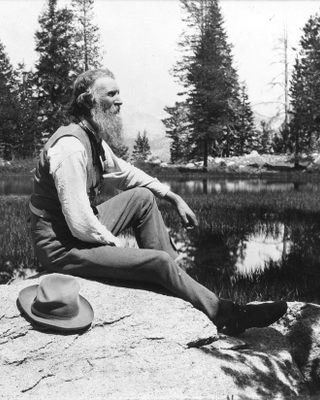

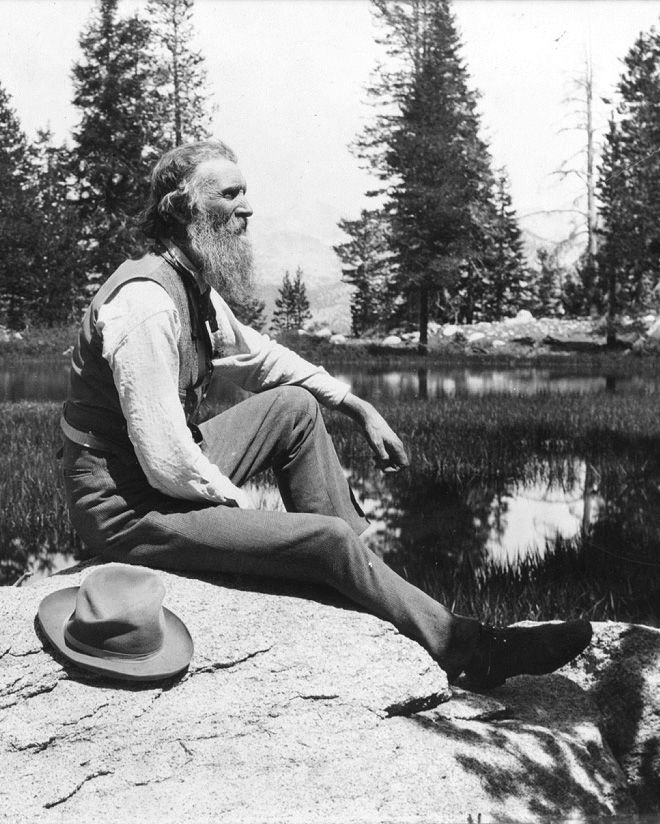

A single, 80-foot-tall giant sequoia (Sequoiadendron giganteum) stands alone near the stunning, Victorian-period Italianate mansion in Martinez, California, where John Muir spent the last 24 years of his life. The tree is almost 140-years-old—a youngster compared to many of its species, which can live for thousands of years and reach an average height of 164 to 279 feet. However this sequoia is significant because it is a living connection to America's most famous and influential naturalist and conservationist, known as the "Father of the National Parks."

Muir had a special affection for California's giant sequoias and coastal redwoods. He referred to them fondly as "Big Trees." While on a trip to the Sierra Nevada in 1885, Muir found this giant sequoia seedling and wrapped it in a moistened handkerchief. He transported it to Martinez and planted it on the property now designated as the John Muir National Historic Site. At the time, Muir's in-laws occupied the house and maintained an orchard on the surrounding land. The tree was placed on a small patch of land and enclosed by a wooden crate for protection. Muir moved to the Martinez house with his family in 1890, and he nurtured the transplanted sequoia there until his death in 1914. The tree continued to thrive and, by 1969, had grown to the height of the roofline.

Sadly, Muir's giant sequoia is now slowly dying. Unknown to him at the time, giant sequoias struggle in the soil and climate of the San Francisco Bay area. Their natural habitat is the western slope of the Sierra Nevada, where they flourish in the mountains' high altitude, rocky soil, and wintry weather. Muir's tree is infected with an incurable regional fungal disease that attacks the tree's vascular system, making it increasingly difficult for the tree to absorb water and necessary nutrients. Unfortunately, the infection can be attributed to the sequoia's less-than-optimal environmental conditions.

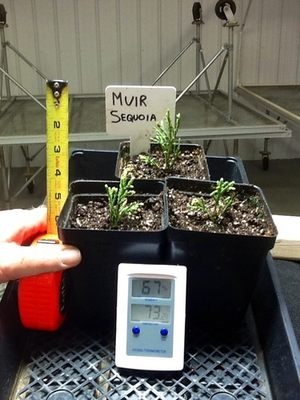

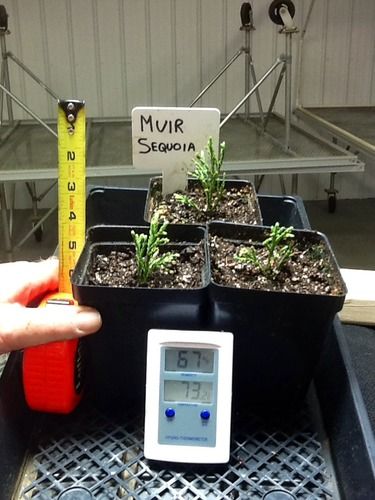

In 2010, it was determined that the tree was seriously ill and unlikely to recover. The park's horticulturist began cloning efforts to preserve the cherished tree and maintain its unique connection to the famous naturalist. Those efforts were unsuccessful. Then, in 2013, the U.S. National Park Service partnered with the Archangel Ancient Tree Archive in Copemish, Michigan, a non-profit organization whose mission is old-growth tree propagation and archiving. Fifteen cuttings were obtained from the tree's crown and shipped to Michigan for cloning. Within six months, the cuttings sprouted roots. There are now miniature sequoia clones safely growing in pots in Michigan.

It is unknown how long Muir's tree will survive. But one of its clones will someday have the honor of replacing its parent when Muir's original giant sequoia is gone.

Related Tags

Know Before You Go

The John Muir National Historic Site is open seven days a week (except Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Year's Day) from 10 am to 5 pm. There is no entrance fee.

Community Contributors

Added By

Published

June 10, 2020