About

As a formerly enslaved man who became employed as a church sexton, John W. Jones was given a responsibility that would make a history buff’s ears perk up. He oversaw the cemetery burials of Confederate prisoners of war who died while being held at a prison camp in Elmira, New York, during the American Civil War.

Jones’ life story is told at his former home-turned-museum. Placards within and outside of Jones’ home give much information on his life. Jones was born on June 21, 1817, on a plantation owned by an Ellzey family that was south of Leesburg, Virginia. In June 1844, in seeing that the aging plantation owner, Sarah “Sally” Ellzey, was giving up control of her property, and out of fear he would be sold, Jones and four other enslaved people decided to flee and head north. The trek to Elmira was 300 miles long; Jones reached the city a month later. At the time, Elmira was a hub for abolitionist activity and an asylum for people who had escaped slavery. It would have some opportunities for Jones, too.

According to Elmira historian and John W. Jones Museum board member Diane Janowski, Jones had no formal schooling when he came to Elmira. Through the help of some locals, he was able to attend a children's school and learn how to read and write and do arithmetic. Janowski also noted that Jones obtained enough of an education to enable him to land a job as sexton of the First Baptist Church in Elmira and earn enough money to buy a house.

With his first home being on the church grounds, and near a railroad station in Elmira, Jones got involved with the Underground Railroad by meeting enslaved people who were hidden on arriving railroad cars and providing them with shelter and other necessities. It’s said that Jones helped some 800 people escaping slavery make their way to Canada.

Jones’ other link to Elmira’s Civil War-related history came through his work. Jones was a caretaker for Elmira’s Woodlawn Cemetery and was contracted to supervise the burials of deceased Confederate soldiers from the Elmira Civil War Prison Camp at the cemetery. The prison camp was in operation for about a year, from July 6, 1864, through July 11, 1865. Close to 3,000 prisoners died due to disease and unsanitary conditions.

In supervising a group of workers, Jones was meticulous in keeping detailed records on every Confederate soldier laid to rest and made sure each one of them received a dignified burial. Jones’ hard work is also credited in giving this area of the cemetery the name of Woodlawn National Cemetery—a status granted by the United States National Cemetery System—thanks to his accurate record-keeping. Jones was paid $2.50 per burial.

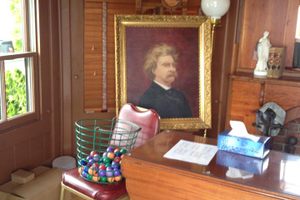

Jones died in 1900 and is buried in Woodlawn Cemetery. He lived in his second home—a farmhouse that apparently was built with wood from the post-war torn-down camp—up until his passing.

Related Tags

Know Before You Go

The house sits on Davis Street and is open to the public.

Published

January 2, 2019