About

In the village of Dolinka, outside of the large Kazakh city of Karaganda, is the former administrative headquarters of KarLag, short for the Karaganda Corrective Labor Camp, one of Stalin's largest gulags. The attractive architecture belies the dark history of the building, which now houses a museum memorializing the victims of political repression all over, and the Soviet gulag system particular.

In its nearly three decades of operation between 1931 and 1959, the administrative center at KarLag processed as many as one million prisoners. Soviet policy was to send people convicted of crimes (real or imagined) out of their home regions where they might generate sympathy among locals. So most of the prisoners housed in KarLag were not Kazakhs.

In the years of World War II and immediately after, the Soviet labor camps were filled with either prisoners of war or simply people of German and, to a lesser extent, Japanese ethnicity who were rounded up and imprisoned. Consequently, the local population of the city of Karaganda was largely ethnically German until the late 20th century.

While the vast Kazakh steppe provided a prison with little need for walls or fences (you can't escape if there's nowhere to escape to) the main reason for situating the Karaganda Corrective Labor Camp in this district was the need for cheap labor for local coal mines. This was especially crucial during wartime. Over time the labor performed here expanded from coal mining to agriculture, railroad engineering, and various scientific work. Famous residents included aircraft designer Andrey Tuplev and scientist Alexander Chizhevsky, who were expected to continue their work within the confines of prison.

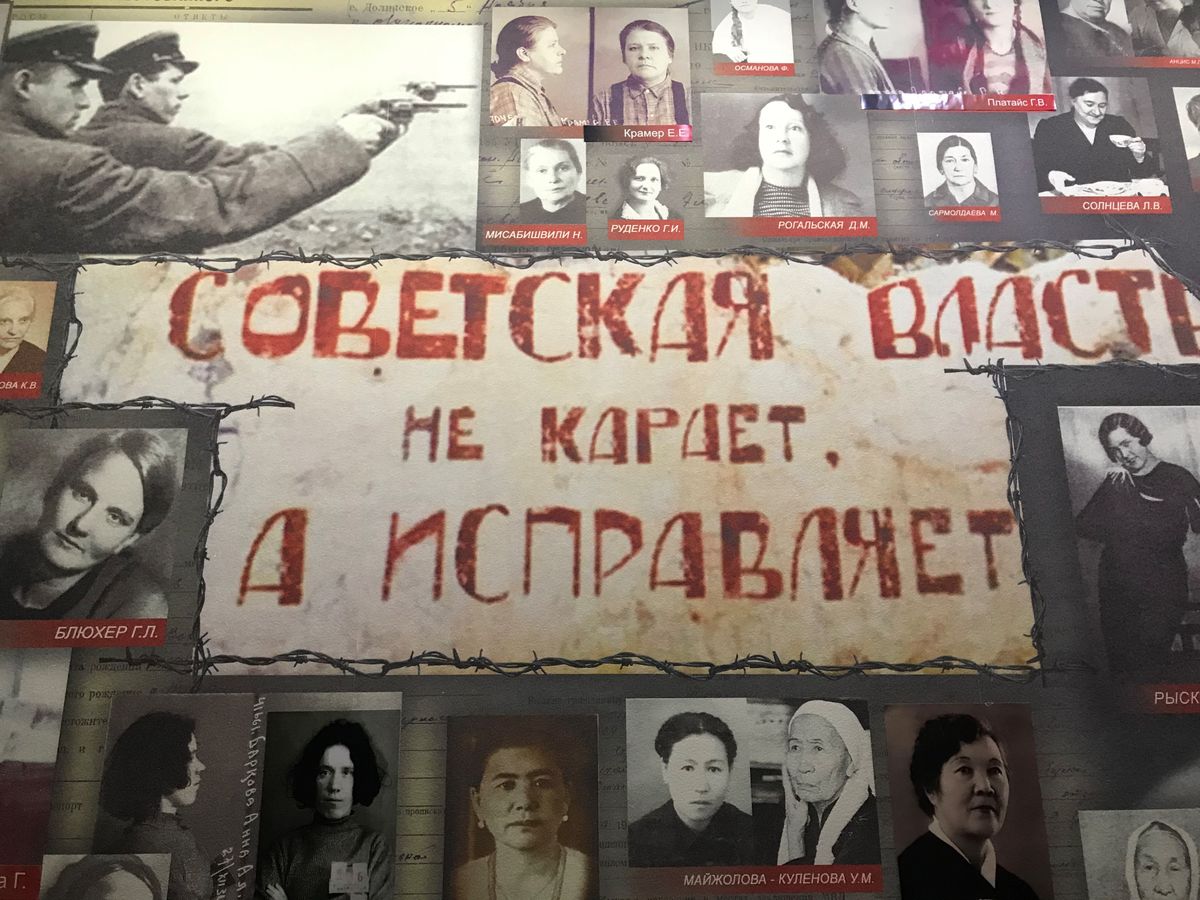

The administrative building includes two floors and a basement. In the basement are recreations of rooms that did not exist in this specific building, but did exist elsewhere in the gulag system: prison cells, medical clinics, torture rooms, and barracks. In the upper floors are themed rooms featuring artifacts and dioramas that tell the stories of life in the camps. Standout features include the many Soviet propaganda posters and the small gallery of art created by prisoners. Unsurprisingly, the subjects deemed appropriate for artistic expression are limited, and feature a lot of images of Vladimir Lenin.

Most of the camp's records were deliberately or "accidentally" destroyed, but a local university continues to work on piecing together the history of the prison. A ledger is provided for visitors to add their contact information and any information they have about relatives who might have been imprisoned here. If the research team finds any information about the prisoner, they will reach out.

Related Tags

Know Before You Go

Budget and hour or two to see the full museum. Many of the exhibits are labeled in Russian, Kazakh, and English, but if you hire a guide you are likely to get more out of the visit as they can share additional stories and context. Tours often leave from Karaganda and include transport, admission, and a guide. If you prefer to go solo, you can negotiate with a taxi driver for round trip driving and wait time while you tour the museum. A fair price is between 5,000-10,000 tenge. Those interested in even more history of the gulag system should visit ALZhIR, just outside the capital city of Astana (now renamed Nur-Sultan).

Central Asia Road Trip: Backroads & Bazaars

A 2-Week, 4-Country Odyssey.

Book NowCommunity Contributors

Added By

Published

April 1, 2019