About

It is hard to imagine Singapore before its modern founding by Stamford Raffles of the East India Company in 1819, even with full knowledge of its earlier history. This cluster of keramats, Muslim saintly shrines infused with the religious practices of the Malay world, provides an intriguing window into Singapore’s pre-British history. Thought to be built around the 16th century (though there are opinions against this), the oldest grave reportedly dates to 1721, and burials continued up to early in the 20th century. The small hillock the keramats reside in was then known as Bukit Kasita, sacred hill.

The wall surrounding the graves are of a hybrid Malay and European styles, and was constructed during the second half of the 19th century. The site contains about 50 graves, banded in green and yellow cloths, denoting Sufi tariqa devotees and royal internees respectively. Certain prominent gravestones are inscribed with the genealogy of the internee. Many pointing towards the royal line of the Johor Sultanate, with its roots in the region intertwined with the fall of the Srivijayan Empire. Hence, the site is also known as Tanah Kubor diRaja, Royal Burial Ground.

The Kingdom of Singapura, according to the Sejarah Melayu (Malay Annals, authored in the 15th and 16th centuries), was founded by the Srivijayan prince Sang Nila Utama in 1299. The following centuries saw the prestigious Srivijayan royal line shift its court from Singapura to Melaka, then Johor. Following the succession crisis caused by Sultan Mahmud Shah III’s death in 1812, the royal line split between a court in mainland Johor and one in the Lingga-Riau archipelago.

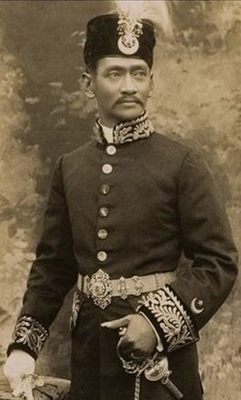

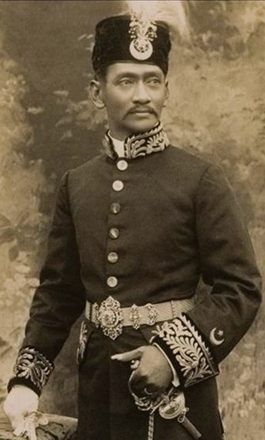

Many descendants from this line are buried here, though the identities of many are unknown. A prominent internee was Sultan Abdul Rahman II (1883-1930), the last sultan of the Lingga-Riau Sultanate who fled to Singapore after the Sultanate was dissolved by the Dutch in 1911. With his royal regalia and dignity stripped, Abdul Rahman II sought to hold on to his lineage, history, and culture by associating with the ancient royal spaces of his forebears. He and his descendants are buried here.

Two prominent graves towards the southeast corner are those of Raja Ahmad Raja Said and Engku Fatimah, a father and daughter pair that descended from Temenggong Abdul Rahman (1755-1825), who was integral to the 1819 Treaty of Singapore, and from whom the modern Johor Sultanate descends from. Abdul Rahman himself was buried in the Johor Royal Mausoleum nearby.

The keramat is today shrouded by vegetation and a small, informal settlement, overshadowed by blocks of public housing. Interviews conducted by the local history interest group The Long and Winding Road showed that the residents outside the keramat were descendants of the custodians tasked by a tunku (royal prince) to oversee the upkeep of the graves. In a hyper-urbanised country where such informal settlements are few and far between (Lorong Buangkok is the last surviving community on the mainland), this site serves as a reminder of how many spaces, buildings, memories, and history were obscured by the development of Singapore after 1819.

Related Tags

Know Before You Go

The keramat is located within Bukit Purmei estate. Access to the keramat is controlled by the custodians. Be respectful to the holy site and to the people living around it, and adhere to the codes of conduct dictated by the custodians.

The immediate area of the keramat is home to a cluster of other holy and royal sites that form a sacred geography of Singapore that is otherwise invisible to both residents and tourists alike. Consider visiting also the keramat of Radin Mas on Mount Faber and the Johor Royal Mausoleum (Masjid Temenggong Daeng Ibrahim) on Telok Blangah Road.

Community Contributors

Added By

Published

May 25, 2020