About

Waters like blue cut glass, lush rainforest, a sweet paddle in the sun on a Sunday afternoon or more adventurous activities that involve holding your breath are all part of tropical north Queensland’s crater lakes, Lake Barrine and Lake Eacham.

The lakes lie in Australia's Crater Lakes National Park, which is in turn part of the Wet Tropics World Heritage Area, an elongated strip of precious tropical rainforest encompassing 9,000 square km, stretching from Cooktown to Townsville. The Great Barrier Reef lies offshore, making this the only place where two interdependent World Heritage areas sit side by side.

The Wet Tropics encompasses mountains, rivers, valleys, streams and cool, isolated cloud forests on mountain peaks, as well as modern cities and towns with everything you’d want in the way of accommodation, food and city lights, and other delights.

And so to the crater lakes, the description a dead giveaway to the region’s violent, volcanic prehistory. Lying more than 700 meters above sea level on the Atherton Tableland south of Cairns, they are explosion craters or maars, formed by the superheating of groundwater as magma rose to the surface around 12,000 years ago.

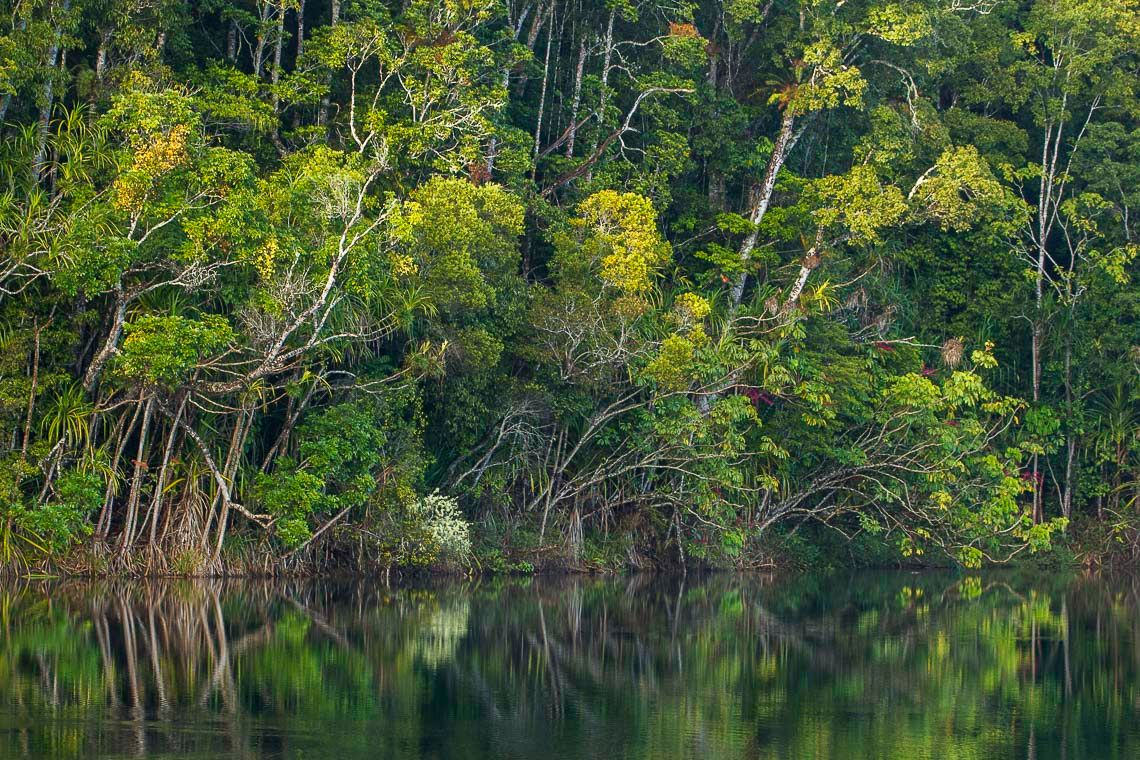

This volcanic history created rich basaltic soils, which support complex forest types with huge buttressed trees, epiphytic plants (those growing on other plants), enormous native figs (some overhanging the water), and at Lake Barrine a pair of 45-meter bull kauri trees with a six-meter girth. Some of the native figs are stranglers, meaning they latch onto other trees and eventually overwhelm them.

These days, volcanic eruptions seem a world away. The lakes' breathtaking beauty and biological diversity is entwined with the traditions of the local Aboriginal peoples. The Ngadjon-Jii and Yidinji are the traditional custodians of Lake Eacham, Lake Barrine, and the surrounding areas. For thousands of years, the rainforest provided everything: spirituality, identity, social order, shelter, food, and medicine. The Ngadjon-Jii and Yidinji peoples’ connection to the land continues, and they ask that visitors appreciate and respect these culturally significant places.

Keen walkers can do a full lap of either lake on relatively easy trails. Other than paddling or swimming the perimeter of the lakes, a walk is the best way to get up close to the wildlife, which includes spectacled flying foxes, amethystine pythons, and a cacophony of birds such as brush turkeys, owls, eastern whipbirds, moorhens and crakes.

Eacham is the more accessible and recreationally popular of the lakes, with a gentle, sloping, lakeside grassy area (usually enjoyed by families, sunbakers, and picnickers on weekends) and steps down into the water for an easy swim. Nine species of fish swim in Eacham and if you stand still (and can bear it) at the steps, the little ones often grow inquisitive and might nibble the skin on your toes, a delightful, if hair-raising, experience.

There are hardcorelocals who take their early morning dip in the cold waters year-round, no matter the weather. At 65 meters deep, the lakes also attract freedivers, who tackle the depths by holding their breath rather than using scuba gear.

"These lakes really are jewels of the Wet Tropics," said Scott Buchanan, Executive Director of the Wet Tropics Management Authority, which bears responsibility for protecting and cherishing this World Heritage Area for future generations. "The region has an astonishing biodiversity and evolutionary history. But you don’t have to be a biologist or ecologist—or a freediver—to enjoy a swim in a beautiful lake on a hot day."

Related Tags

Published

May 29, 2024