About

In 1885, a thousand miles away from the city of Chicago, Charles Lapham built his winter home inspired by the Great Fire. He had survived the conflagration at the age of 19, and the experience would follow him and inform his architectural whimsy.

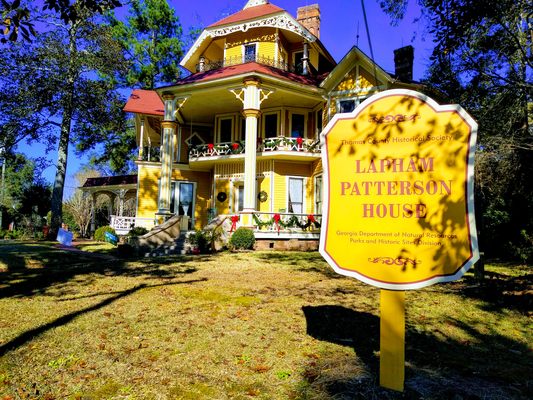

The Queen Anne-style home is a National Historic Landmark and considered one of the more “forceful” examples of Victorian eclectic architecture in the state of Georgia. It is also a forceful expression of Lapham's pyrophobia, containing more exterior doors than it does rooms (24 of the former, 19 of the latter) as well as unique windows built to afford easy egress. The numerous exits required the entire structure to be rounded into a horseshoe shape. This peculiar design consideration is strikingly evident on the first floor, where a courtyard is lined with an ominous row of doors installed, not for entry to the home, but for escape.

The exterior is detailed with fishtail shingles and flaming scrollwork ornament. Imposing columns flank the entryway. At the center of the interior is a hexagonal dining room. Here, a cantilevered balcony wraps around the unique double flue chimney, allowing visitors to walk through a fireplace. The flues reconnect at the roof which resembles a fireman’s hat.

The home is filled with prismatic light as the sun shines through numerous rainbow stained glass windowpanes. The third floor windows provide one of the most mysterious elements of the home. The exterior bargeboard is aligned so that on the spring and autumn equinoxes, the sunlight creates a horned silhouette in front of a central dais in the third-floor parlor. The animal head appears between six-pointed stars projected through the outside scrollwork. The tauriform is said to represent Mrs. O’Leary’s Cow, the legendary bovine deemed responsible for the Great Chicago Fire. No one knows if the astronomical alignment was intentionally placed, but if it was, the home would be the only known American Victorian property to harbor this phenomenon.

Though it may be peculiar for a building in Thomasville, Georgia to be inspired by the Great Chicago Fire, the disaster had a major impact on architecture in the 19th century. As the scholar Ross Miller describes in his book American Apocalypse, “Chicagoans exposed their psyches in the odd assortment of things they built.” This appears in spades with Lapham, who seemed to not only fear fire, but also hold reverence for it.

In the decade the Lapham family wintered in Thomasville, five children were born. One died in the home, and two were later institutionalized for intellectual disabilities. Charles’s business fell apart, and later his marriage. Divorce was rare at the time, leading the couple to informally separate. His wife Emma continued to provide him with a living allowance. She then moved to Arizona with her sons to start a cattle ranch. In a tragic accident later, a kerosene lantern overturned in Emma’s room and she perished in the fire.

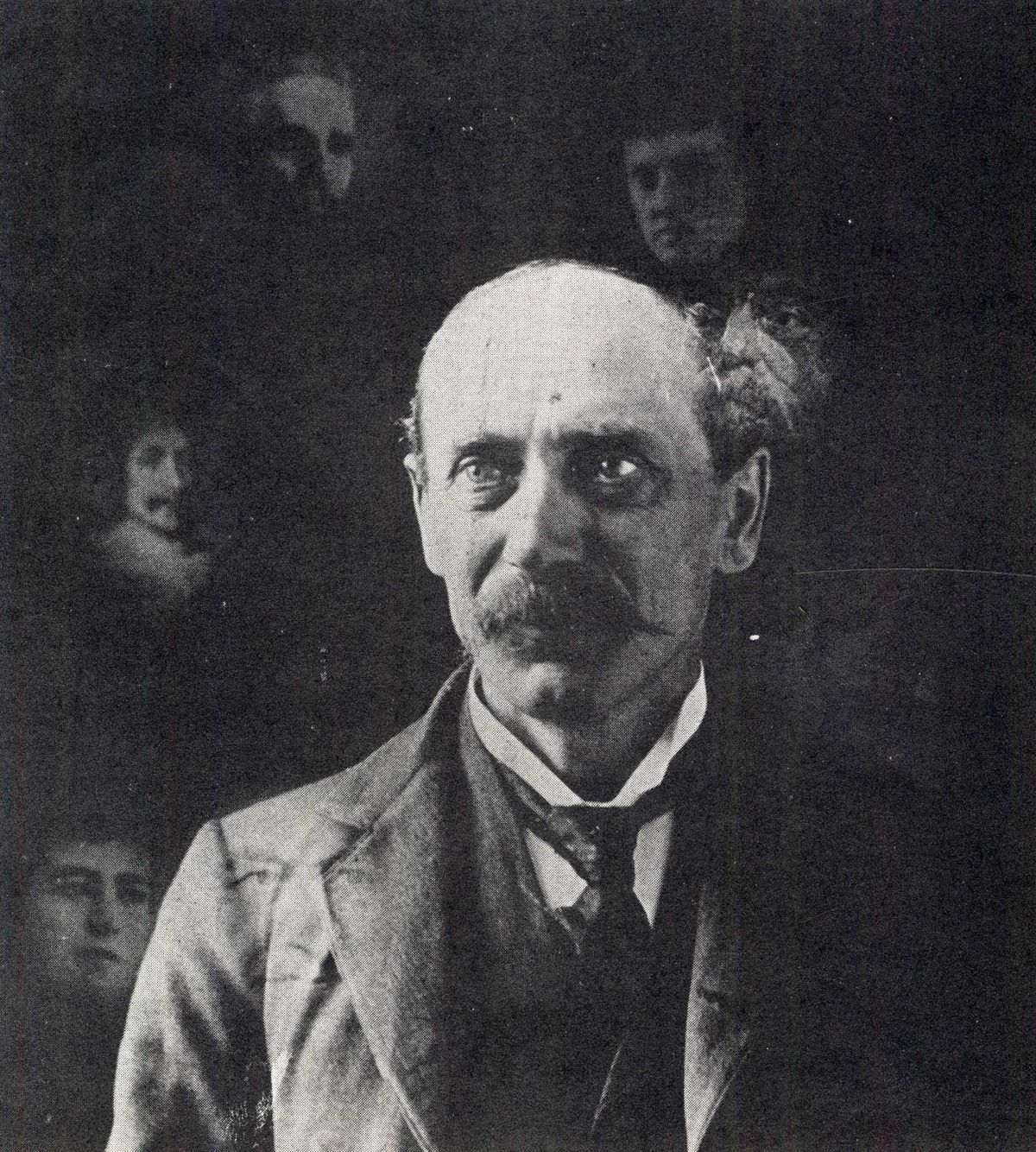

The only remaining portrait containing both Charles and Emma Lapham was taken after a séance in Chicago. Emma had already died and is pictured in spirit form alongside other spectral figures, including the suffragette Lucretia Mott, and a Greek Deity “who treats and cures by fire.” The memento was not entirely uncommon; spirit photographs were popular in the late Victorian era, back when cameras seemed less like technology and more like magic. The hidden eeriness of the picture is in the detail of fire, which followed the family through their tragic turn.

None of the sons had children of their own, thus ending the family line. Charles Lapham died in San Diego and was subsequently cremated.

Special thanks to Martin Willett, the Lapham-Patterson House's first curator, for serving as an invaluable source of information on the site.

Related Tags

Community Contributors

Added By

Published

February 29, 2016